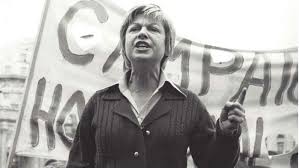

Trailblazing lesbian journalist and activist to be honoured with rainbow plaque

One of the few out lesbians in the public eye, Jackie Forster, who also worked under the name Jacqueline MacKenzie, was an actress before forging a successful career in journalism.

In the 1960s, she joined the Minorities Research Group and wrote for the UK’s first lesbian-specific publication, Arena Three, and set up the long-running magazine and social group, Sappho.

After coming out publicly, she joined the Campaign for Homosexual Equality and marched in the first London Pride parade in 1971. She went on to be a member of the Greater London Council’s women’s committee, a curator for the Lesbian Archive, and set up Daytime Dykes.

In 2017, she was celebrated in a Google Doodle on what would have been her 91st birthday.

After Forster died in 1998, aged 71, writer and academic Gillian Hanscombe told The Independent: “If she had served any cause other than lesbian rights, she’d have been festooned with honours.”

Forster’s plaque will be will be unveiled on 26 February.

Supported by the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, the Rainbow Plaques scheme has sought to identify and make visible LGBT+ history in local communities up and down the country.

“It’s fantastic to see a new rainbow plaque unveiled in Warwick Avenue to celebrate the life of Jackie Forster,” Khan said. “These plaques honour the huge contribution that our LGBTQIA+ communities have made, and continue to make, to life in our capital. So it is fitting that we remember Jackie’s significant role in promoting and championing LGBTQIA+ rights.

“Our diversity is what makes London the greatest city in the world and we will continue to ensure that everyone feels represented in our public spaces, as we continue to build a fairer and safer London for everyone.”

Anne Lacey, Forster’s partner, described the plaque as a “fitting tribute to a wonderful woman and a great character in the history of LGBTQIA+ rights”.

She went on to say: “Jackie spent the last half of her life working unceasingly for LGBTQIA+ rights and visibility. From the day she came out at Speakers’ Corner (in London’s Hyde Park) in 1969, she fought for the celebration of the word ‘lesbian’.”

If you’re raging that ‘Netflix made Alexander the Great gay’, it’s time to learn some LGBT+ history

Matt Cain, author of “One Love” wrote this article for The Guardian on 13 February 2024.

At the start of this LGBT+ History Month, Netflix unveiled its new series about Alexander the Great, only to see complaints that the streaming service had “turned him gay”. When these drew the response that Alexander is widely believed to have had same-sex relationships, a typical reply was that this was “unproven speculation”. As a patron of LGBT+ History Month, I see this as an opportunity to argue for the importance of knowing our queer history.

For centuries, LGBT+ history has been wiped from the record. Oppressors have found it all too easy to deny our existence because in most of the world – for most of history – our lives have had to be led in secret. Exposure could lead to familial rejection, social and professional ruin, imprisonment, torture and even execution. Any evidence of queer lives that did exist was often destroyed, sometimes by descendants keen to protect reputations.

The Renaissance artist Michelangelo, for example, was known to have had several relationships with men, but burned all his papers before he died. And in 1623 his great nephew published an edition of his poetry with many of the masculine pronouns changed to feminine ones (an act of cultural vandalism that wasn’t rectified until the 19th century).

Of course, labels such as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender didn’t exist for most of history, making it impossible to know definitively how any figure would have identified in their own time. But it would be ridiculous to use this as justification for erasing us from the past. The understanding of our sexuality contributing to any sense of identity (rather than just sexual activity) may be a relatively modern one, but we have always been here.

It doesn’t help that, as queer people, we’re one of the few minority communities who don’t often have parents from the same minority, so little understanding of our cultural heritage is passed down through the generations. All of this has allowed historians to straightwash the past, to write off our relationships as passionate or intimate friendships, or to declare we were married to our work.

Years of campaigning – not to mention a Hollywood film – means that most people now know the name Alan Turing. But the story of Bayard Rustin is only just coming to prominence, thanks to another film: he was one of the leading organisers of the black civil rights movement and a key adviser to Martin Luther King, but he was kept in the background to avoid his sexuality damaging the movement.

And how many people have heard of Ben Barres, a transgender neurobiologist whose pioneering research at Stanford University revolutionised our understanding of brain cells?

Or that the astronaut Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, had a 27-year relationship with a woman?

And did you know that Florence Nightingale wrote in a letter in 1861: “I have lived and slept in the same beds with English countesses and Prussian farm women. No woman has excited passions among women more than I have”? Why historians ever believed she was celibate is beyond me.

In 19th-century Russia, Tchaikovsky lived life as a gay man with a degree of openness that was remarkable for the time, writing about his feelings in letters to friends and his brother, who was also gay. He even signed one of these using the female name he’d given himself, Petrolina.

But although he enjoyed close friendships with gay men (one, Petashenka, used to pop round to his place to ogle the cadet corps opposite), other letters show that he never stopped wanting to change his sexuality, lived in fear of being outed and disgraced, and struggled with alcoholism and depression.

Like many gay men of his time, he briefly married a woman to maintain a respectable front, but she later accused him of using her to hide his “shameful vice”. Tchaikovsky found release in his music, and this could be why his work has such a joyous quality. Likewise, the range of emotions he experienced in life could have given his ballet scores the depth necessary to tell dramatic, sweeping stories.

Today, Tchaikovsky is considered a national treasure in Russia, but official accounts of his life remove all mention of his sexuality, as does the Tchaikovsky State House-Museum near Moscow. Meanwhile, the widespread persecution of queer people continues in the country, as does anti-queer legislation and the state-sponsored spreading of shame.

When I visited Moscow in 2017, I met LGBT+ people and heard their shocking stories, visited queer venues and saw signs in shop windows announcing “No faggots allowed”. But if Tchaikovsky’s queerness was widely understood and acknowledged as part of his artistry, it would be more difficult for Putin and his government to continue their oppression – or at least to argue that queerness is a foreign import and somehow “un-Russian”.

For me, the response to Netflix’s series about Alexander the Great sums up why we need LGBT+ History Month, and the story of Tchaikovsky is a chilling illustration of the dangers of not knowing our queer history.

Understanding history is empowering, and for too long queer people have been disempowered. History can teach us – and others – that we’ve always made a contribution to society, help us understand our place in the modern world and give us pride in who we are.

LGBT+ History Month Coming to an End

Try this quiz to see what you have learnt. Don’t worry the answers are below.

Out In The City Women’s Meeting

Reminder that Out In The City Women’s meeting is on Thursday, 27 February 2025 from 2.00pm to 4.00pm. The meeting is at Cross Street Chapel, 29 Cross Street, Manchester M2 1NL and is a drop in. There is no need to book.