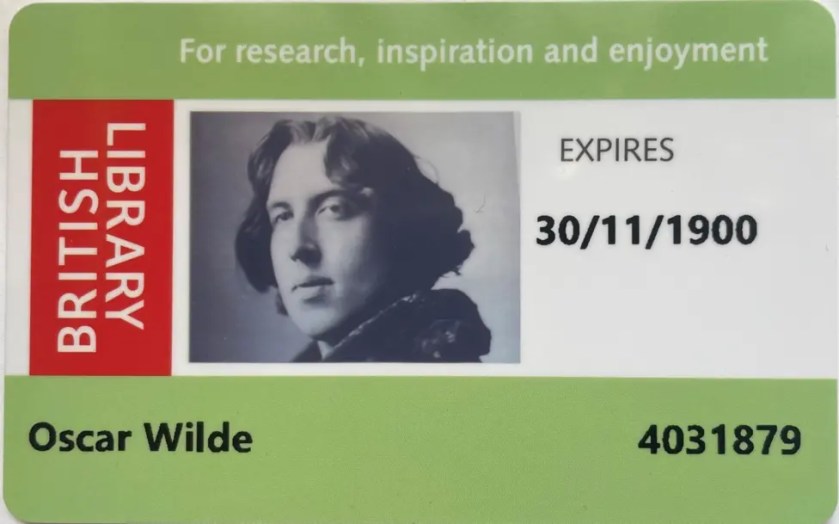

Oscar Wilde’s library card reissued

The date of Oscar Wilde’s death, 30 November 1900, has been used as the new card’s expiry date

The British Library has honoured late Irish writer Oscar Wilde by reissuing a reader’s card in his name, 130 years after his original was revoked following his conviction for “gross indecency”.

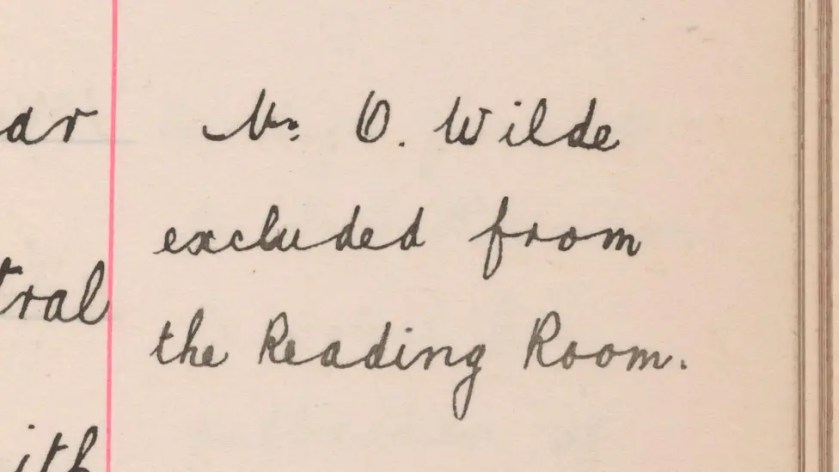

The celebrated novelist, poet and playwright was excluded from the library’s reading room in 1895 over his charge for having had homosexual relationships, which was a criminal offence at the time.

The new card, collected by his grandson, author Merlin Holland, is intended to “acknowledge the injustices and immense suffering” Wilde faced, the library said.

Mr Holland said the new card is a “lovely gesture of forgiveness and I’m sure his spirit will be touched and delighted”.

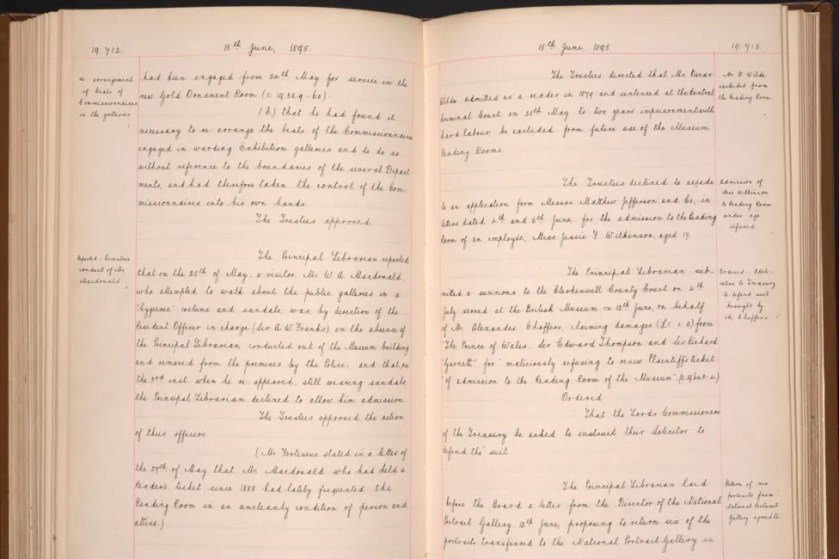

The decision to revoke Wilde’s pass for the library – then the British Museum reading room – was recorded without comment in the trustees’ minutes for 15 June 1895.

He had been in prison for three weeks at the time after being handed a two-year prison sentence with hard labour.

The author was convicted after he lost a libel trial against Lord Queensberry, who had accused him of being homosexual after discovering that his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, aka Bosie, was Wilde’s lover.

The library regulations at the time said anyone convicted of a crime should have their card revoked.

‘Letter from prison meant so much’

The British Library holds handwritten drafts of some of Wilde’s most famous plays including The Importance of Being Ernest, An Ideal Husband, A Woman of No Importance and Lady Windermere’s Fan.

Its collection also includes De Profundis, the letter he wrote to Bosie from Reading Gaol.

Mr Holland collected the new card at a ceremony at the venue on what would have been his grandfather’s 171st birthday.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, Mr Holland said he felt both “proud” of his grandfather and slightly burdened by the responsibility of handling his legacy.

“People will so often write in to me and say, ‘I cannot tell you how much your grandfather’s De Profundis meant to me’,” he explained.

“It has a note of positivity at the end … he’s going to come out of prison and do something again.

And people have written to me saying, ‘In a moment of terrible depression about my own life I read De Profundis, and I just wanted you to know that your grandfather’s letter from prison meant so much to me’.”

Dame Carol Black, chair of the British Library, described Wilde as “one of the most significant literary figures of the nineteenth century”.

She said that by reissuing his library card, “we hope to not only honour Wilde’s memory but also acknowledge the injustices and immense suffering he faced as a result of his conviction”.

She added that they were “delighted” to welcome his grandson – who is the author of a new book, After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal – to receive the library card on his behalf.

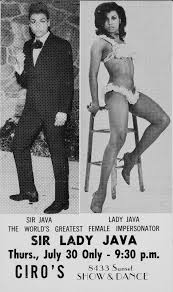

Meet Sir Lady Java, the 1960s trans performer

Did you know that Los Angeles once had a law that banned drag performances? That’s why we’re celebrating Sir Lady Java, a trailblazing transgender activist who fought that law in the 1960s.

Almost half a century before “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and “Pose”, Sir Lady Java was a popular dancer, comedian and drag performer in Los Angeles’ nightlife scene, working alongside Sammy Davis Jr and Richard Pryor among other people.

Born and raised in New Orleans, she moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1960s. She worked as a waitress at the Redd Foxx Club on North La Cienega Avenue in what is now West Hollywood.

At the same time Sir Lady Java was making a name for herself, the LA Police Department began cracking down on shows featuring “female impersonators” or anyone dressing in drag. As Sir Lady Java’s popularity grew, she became a target for the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), who used Rule Number 9 to shut her down.

Rule Number 9, passed in 1958, was a municipal code that prohibited bar owners from hiring anyone who performed as or impersonated the opposite sex.

In 1967, when Sir Lady Java wanted to continue performing at the Redd Foxx Club, the owner applied for a performance permit but was denied.

In response, Sir Lady Java organised protests and picketed outside the Redd Foxx Club, demanding her right to work.

After her protest, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit on Sir Lady Java’s behalf against the LAPD. However, the court refused to hear her case because only bar or club owners could file such a lawsuit. Since no owner would step forward, the case was dismissed.

Still, Sir Lady Java made history because she was the first person to challenge the code in court.

Two years later, Rule Number 9 was overturned. Sir Lady Java was able to return to the stage and continued performing in Los Angeles nightclubs throughout the 1970s and early 80s.

Sir Lady Java laid the groundwork for future generations in the fight for transgender rights.

In 2022, her trailblazing efforts were recognised; the 79-year-old was the community grand marshal in the LA Pride Parade.

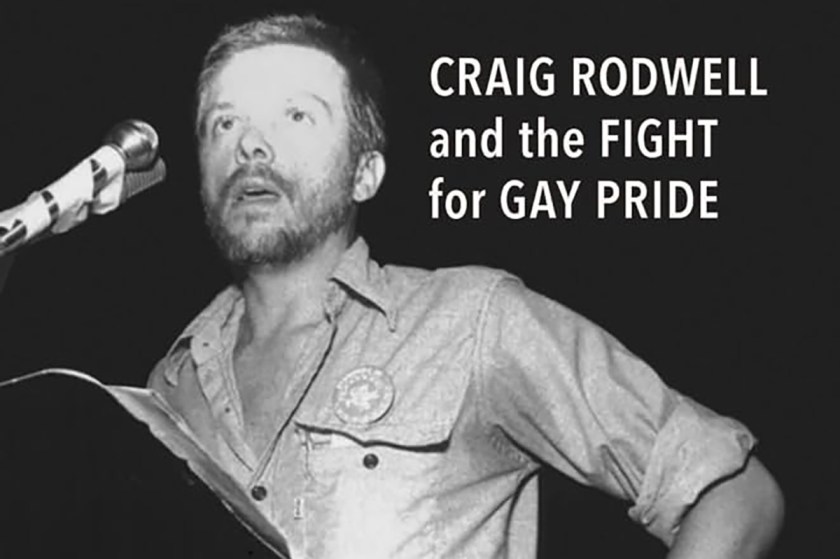

New book celebrates gay rights pioneer

Craig Rodwell is, sadly, not nearly as well known as he should be, given his accomplishments. He opened the first bookstore devoted to gay and lesbian literature. He led a chant of “Gay power!” at the Stonewall riots and contributed many articles about the struggle for equality and fair treatment. He helped organise the first Pride march. Thankfully, journalist John Van Hoesen’s new book, “Insist that They Love You,” tells Rodwell’s story.

Rodwell was born in Chicago in 1940 and spent his early years at a Christian Science-run children’s home. As a teenager, he roamed the streets, connecting with older men. One of those lovers was arrested and later died by suicide. He moved to New York to study dancing and joined the Mattachine Society, one of the first groups involved in “gay liberation.” He dated Harvey Milk, a challenging relationship, as the older Milk was still closeted while Rodwell was out and deeply involved in the cause. This was when being gay was a crime and public exposure risked getting fired and evicted.

In 1967, he opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, which openly displayed gay and lesbian books and materials. It had large, inviting windows, different from the typical places gay people congregated. Many walked past it, working up the courage to go in. Once they did, they found a welcoming place where they could learn and connect with others. Van Hoesen writes about the diversity of the Bookshop’s employees, gay, lesbian, black, and white, who all loved the sense of community and purpose Rodwell created.

That same year he helped form the group Homophile Youth Movement in Neighbourhood and created their periodical HYMNAL. He wrote many articles for them and later, for QQ Magazine, describing the forces in straight “heterosexist” society, as he termed it, against gay people. He wrote about mafia-controlled gay bars, including the Stonewall Inn, seedy places that overcharged for watered-down drinks. He decried how the law was used to persecute gay people, describing his arrest for wearing “too-short” swim trunks. He explained what to do if arrested: never speak without a lawyer present and never provide names of other gay people. Van Hoesen helpfully includes these articles in an appendix.

Rodwell’s history of activism is impressive. In 1966, he participated in a “sip-in” protesting a law forbidding bars serving alcohol to homosexuals; it took three attempts before one refused to serve him. He and his partner happened by the Stonewall Inn when the riots began, offering the protesters support. He helped lead a group that picketed Independence Hall in Philadelphia every year as an “Annual Reminder,” arguing with organiser Frank Kameny over the required conservative dress code.

He organised the first Pride march in 1969. One of the biggest challenges was getting all the different gay rights groups, with different objectives, to work together. The police only issued the permit the morning of the march. Among the book’s photos is one of Rodwell and his partner afterwards, looking exhausted but happy.

Rodwell never sought the spotlight for his work, always working with others. Yet he often chaffed against many of the organisations’ philosophies, one of the few Mattachine Society members to use his real name. He refused to sell pornography in the Bookshop, or work with gay business owners funded by the mob. He even threw some customers out. Let’s hope this biography shines more attention on this lesser-known leader of the gay rights movement.

‘Insist That They Love You: Craig Rodwell and the Fight for Gay Pride’

By John Van Hoesen

c.2025, University of Toronto Press

£22.99 / 432 pages

We are the Bridge

We were born in one world … and grew up in another.

A world where summers meant open windows, the hum of a box fan, and the smell of fresh-cut grass.

Where neighbours waved from their porches, and if your bike chain broke, you didn’t Google it – you knocked on a door and someone came out with a wrench.

We lived in a world built on patience.

We waited for letters to arrive.

We waited for the library to open.

We waited for our favourite song to play again on the radio – and when it finally did, it felt like magic.

Then, almost overnight, everything changed.

Phones shrank. Music became invisible.

News arrived before the coffee finished brewing.

We learned to type, to swipe, to tap.

We learned to talk to machines – and to have them talk back.

We’ve seen milk delivered to the door in glass bottles …

and we’ve scanned groceries without speaking to a single cashier.

We’ve dropped coins into payphones …

and we’ve made video calls to loved ones across oceans.

We’ve known the deep quiet of a world without notifications –

and the noise of one that never stops buzzing.

And sometimes, the younger ones look at us like we’re behind.

But what they don’t see is this:

we know both worlds.

We can plant tomatoes and write an email.

We can tell a story without Google – and then fact-check it with Google.

We know the weight of a handwritten letter and the reach of a message sent in seconds.

We’ve lived long enough to understand that you can change without losing yourself.

That you can honour where you came from while still learning where the world is headed.

We’ve buried friends and welcomed grandchildren.

We’ve seen diseases disappear and new ones arrive.

We’ve unfolded paper maps – and followed glowing blue lines on GPS.

We’ve sent postcards with stamps – and emojis with a single tap.

And maybe that’s our greatest gift:

the memory of a slower, gentler time,

and the courage to adapt to a world that never sits still.

We can teach the young that not everything needs to happen instantly.

And we can remind our peers that it’s never too late to try something new.

Because that’s what we are –

the bridge between what was and what will be.

And as long as we keep standing strong,

the world will always have something solid to cross on its way forward.

Because every generation builds the road a little further – and ours?

Ours remembers both the dirt path and the highway

I’ve enjoyed this email today. Thanks again Tony for all your work. Chris Wilde.

LikeLike

Hi Tony

Just to ask if Peter & myself need to book for Staicase House visit 6th Nov?. Is the group meeting at Wetherspoons 11.30?

Thanks Nick x

LikeLike