The Whitaker

Twenty of us set out from Shude Hill Interchange on Bus X43 to Rawtenstall. We stopped for lunch but due to the size of our group we split up into various cafes, before meeting up again. Some settled into The Queen’s Arms whilst others enjoyed the delights of The Fitzpatrick – Britain’s last original temperance bar.

It was a fifteen minute walk (uphill!) to The Whitaker, but it was well worth the exercise. We had come to take part in the installation of an exhibition Contagious Acts.

Contagious Acts is a solo exhibition by artist Jamie Holman at The Whitaker Museum & Art Gallery. The exhibition explores the politics of gathering from medieval battlefields to dance floors.

Jamie explained what the exhibition was about:

- The exhibition considers how gathering spaces are battlegrounds of power and protest and sites of cultural production and resistance.

- He combines medieval art history with contemporary iconography.

- He explores the politics of collective gatherings and how they are tied to class, identity and belonging.

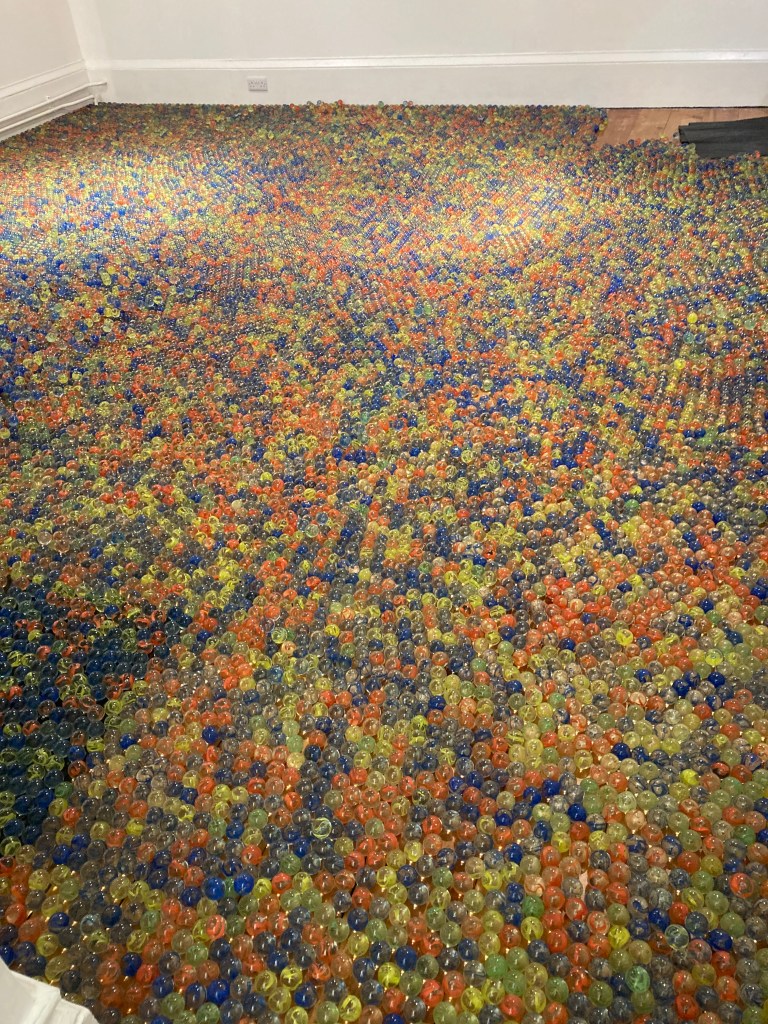

The exhibition fills the gallery space with marbles, as a symbol of resistance to state control. We had fun adding extra marbles to the gallery space.

More photos can be seen here.

Gay Couple’s Archive Reveals ‘Peaceful Life’

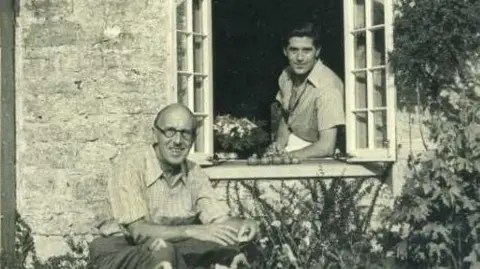

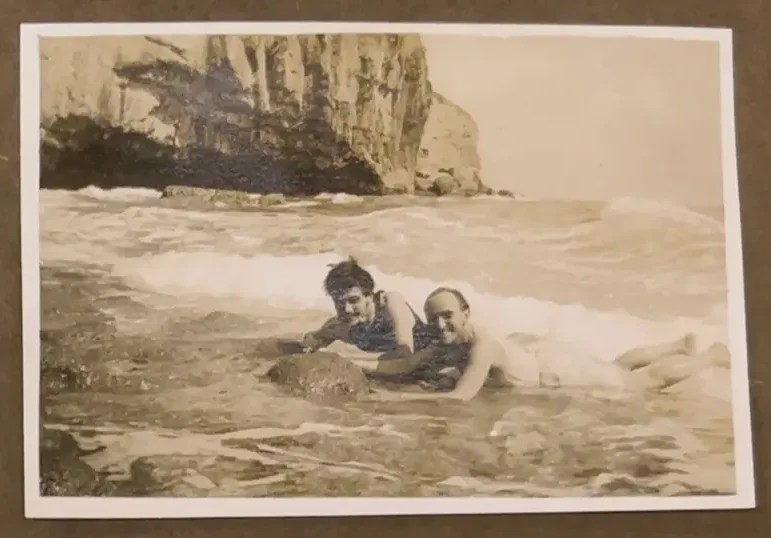

The lives of a gay couple who lived in a Dorset village for nearly six decades have been turned into an exhibition.

Norman Notley and David Brynley moved to Corfe Castle in 1923 and lived openly as a couple, despite homosexuality being illegal at the time.

The two men were successful musicians who sang together in Britain and the United States and they had many friends in the art world.

Photographs and diaries on display at Dorset Museum reveal they lived peacefully with the local community for 57 years until their deaths.

In 1973, local people organised an event for the couple to celebrate their 50 years in the village.

Museum director Claire Dixon said: “They were known as ‘the boys’ quite affectionately by the community.

They didn’t throw the party, the community threw it for them.

When lots of people were having to hide the fact that they were gay, or think about their behaviour in public space, it seems that they were able to live quite a peaceful life in the village.”

The couple shared a passion for creating art as well as collecting and Notley bequeathed his collection of paintings to Dorset Museum.

Despite being able to live authentically, the only image in the collection of them being affectionate to one another is a photo of Brynley kissing Notley on the cheek.

Notley died in 1980, aged 90, and Brynley a year later, aged 81.

Maisie Ball, an archaeology student at Bournemouth University, began digitising the couple’s photographs and transcribing their journals and letters as part of a work placement at the museum.

She said: “Being able to share their story has been so important as there are not many collections like this that give a glimpse into the lives of LGBTQ+ people from this time period.

The photographs that have stuck with me the most are the ones with their many dogs and the rare few of Norman on his own, where you get to see a glimpse of his personality.”

The display, curated by Ms Ball, with advice from Prof Jana Funke of the University of Exeter, is on display throughout February to coincide with LGBT+ History Month.

There is only one photograph of the couple showing physical affection.

Queer Treasures of the Manchester Central Library – 2

Thanks to Arthur Martland for the second of a short series of articles about queer treasures that are currently to be found in the Archives held at Manchester Central Library.

‘Curiosities of Street Literature’ by Charles Hindley

In 1871, Charles Hindley published a collection of broadsides and broadsheets that he had gathered over the previous six decades. As Michael Hughes in his Introduction to a later reprinting of the volume explains, ‘Broadsides (single unfolded sheets of paper printed on one side only) and broadsheets (printed on both sides) … were the first medium of mass communication. They were simple pieces of paper on which was printed the news of the day, sermons, politics, satire, public events, proclamations, romantic and humorous tales, descriptions of murders – anything, in fact, which would excite popular interest and be saleable’.

Hindley’s book helped to preserve many of these ephemeral documents, including four of notable queer interest.

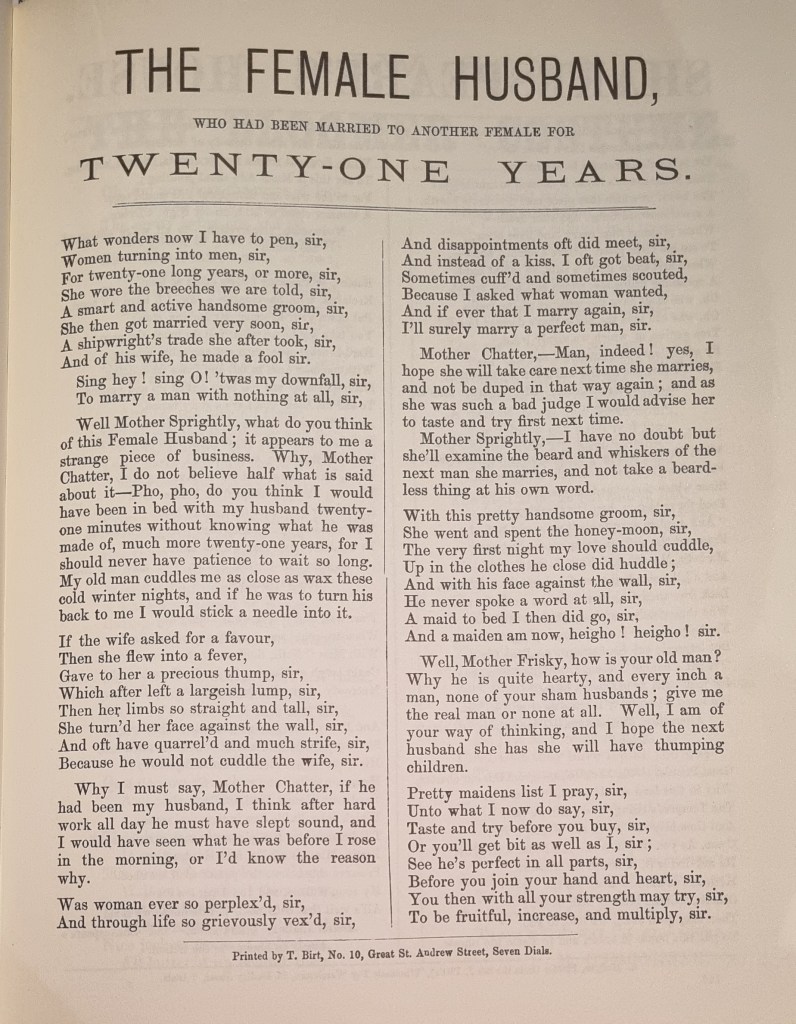

The first is a ballad concerning ‘The Female Husband, who had been married to another female for twenty-one years’ which begins –

What wonders now I have to pen, sir

Women turning into men, sir,

For twenty-one long years, or more, sir,

She wore the breeches we are told, sir, (p119)

The whole is a warning to young ladies to ‘Taste and try before you buy’ and ‘See he’s perfect in all parts, sir, Before you join your hand and heart, sir’.

The ballad refers to the case of James Allen, a trans man. In 1807, Allen, a sawyer, had married Abigail Naylor at St Giles’s church in Camberwell. After his death from an accident at work in 1829, an autopsy was conducted at St Thomas’s Hospital in London and his sex declared to be female. His wife Abigail said she was not suspicious of her husband’s sex because he was ‘so strong’. A sensational pamphlet called ‘An Authentic Narrative of the Extraordinary Career of James Allen, the Female Husband’ was soon published after his death. Throughout most of the work though Allen is referred to by male pronouns and hateful people who tried to disrupt his funeral are described as ‘ignorant beings of the very lowest class’.

A second ballad of interest is the ‘She He Barman of Southwark’, a song based on the life of Mary Ann Walker. Mary loved dressing up in male clothing from a young age and spent much of her early life in helping her father run a pub. When he died in 1860, Mary donned male clothing, presented herself as a man and took a number of jobs that were usually, at that time, strictly reserved only to men. Mary worked as a porter at Jesus College, Cambridge, an engine cleaner for the Great Northern Railway at King’s Cross Station and spent two years as a ship’s steward for the Cunard Line, before taking a job as a dock labourer. In 1867 she assumed the name of Thomas Walker and became a barman in the Royal Mortar Tavern in Southwark. As the ballad puts it –

She did not like the petticoats,

So she slipped the trousers on,

She engaged herself as a barman,

And said her name was Tom. (p141)

Tom was subsequently however accused of stealing monies after marked coins were found in his possession and swiftly remanded into custody pending trial. On his reception into the prison, the gaoler described him as ‘having a full masculine face, rather sunburnt, hair cut short and slightly curled and a masculine speaking voice’. When Thomas was obliged to take a bath though, he was forced to confess to being, anatomically-speaking, female. On his conviction at trial he was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Nevertheless, on leaving gaol, he continued to live as a man and obtained work on the Great Western Railway but lost that job when his landlady discovered his secret. After several other unsuccessful jobs, Tom eventually found fame on the Music Hall stage by returning to his former name of ‘Mary’.

Appearing on stages across the country, he was billed as ‘Mary Walker, the female Barman’, and frequently dressed in male clothing or naval uniform, giving a ‘sort of auto-biographical recitation to the tune of Champagne Charley’.

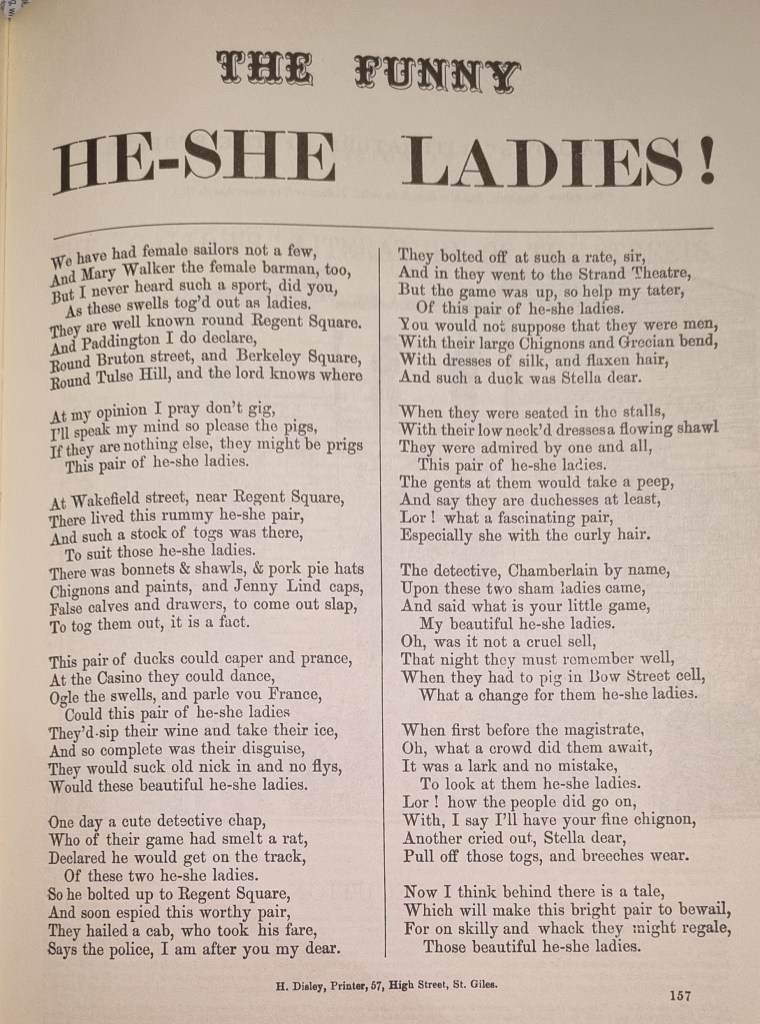

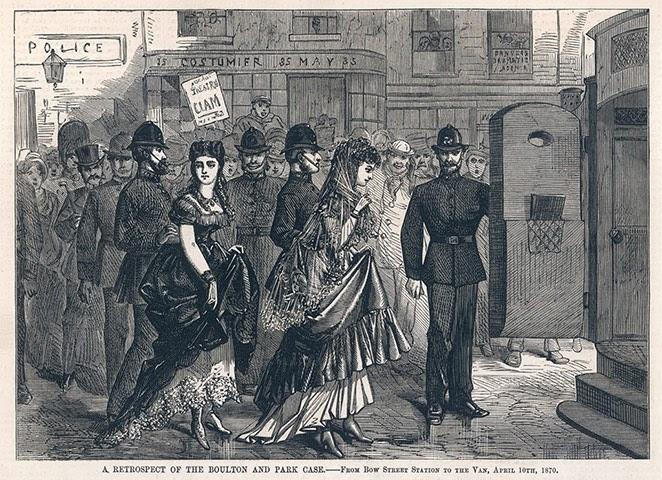

A third ballad of queer interest is ‘The Funny He-She Ladies!’ which tells the tale of Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park, better known now perhaps as ‘Fanny and Stella’. The two men became known for their flamboyant clothing and for their dressing in what was seen as ‘female’ attire; as the balladeer sings –

You would not suppose that they were men,

With their large Chignons and Grecian bend,

With dresses of silk and flaxen hair,

……. With their low-neck’d dresses a flowing shawl

They were admired by one and all,

This pair of he-she ladies (p157)

Over several nights Boulton and Park were followed by police detectives as they cruised, in full drag, around the streets of the West End. Eventually, and perhaps inevitably, they were arrested and charged with committing the abominable crime of buggery, conspiring to induce and incite other persons feloniously with them to commit the said crime; and with disguising themselves as women and frequenting places of public resort thereby to openly and scandalously outrage public decency and corrupt public morals. In 1871, after six sensational and widely reported days at trial, the cases against them collapsed and they were declared not guilty. After their acquittal, the two returned to work on the stage, touring Britain as a theatrical act, but the scandal of their arrest never left them.

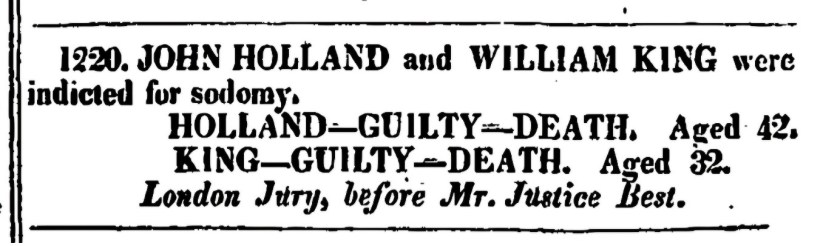

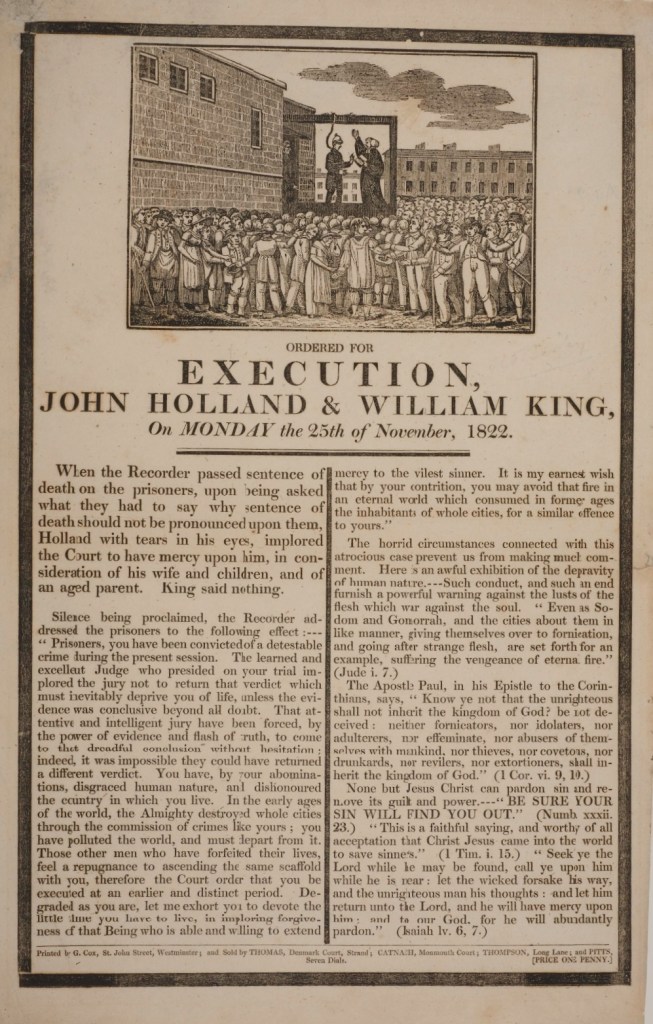

The final part of Hindley’s book concerns what he terms as ‘the Gallows Literature of the Streets’. This section deals predominately with broadsheets that dealt luridly with crime and public executions. The fourth item of queer interest is the broadside recording ‘The Sentences of All the Prisoners in the Old Bailey’ on ‘Wednesday 11th September 1822’. Amongst the list of hapless felons are the names of Holland, King and North, who were to be executed ‘for an unnatural crime’. William North (61 years old) was a retired schoolmaster in the Royal Navy who had been accused of attempting to rape a younger male.

But John Holland (42 years old) and William King (32 years old) however, were heavily condemned as they appear to have had consensual contact. Their ‘unnatural crimes’ together were seen as so despicable that the official record of their trial contains no details of what precisely was alleged to have happened, simply that they were both convicted of sodomy. Courts, not unusually at that time, failed to fully record evidence details which the judges and magistrates in charge deemed unsuitable for the public to hear about.

The judge, Mr Justice Best, was scathing in his closing comments at their trial, as recorded in various newspapers at the time –

‘Prisoners, you have been convicted of a detestable crime during the present Session … You have, by your abominations, disgraced human nature, and dishonoured the country in which you live. In the early ages of the world, the Almighty destroyed whole cities through the commission of crimes like yours; you have polluted the world, and must depart from it.’

The judge continued, ‘Those unfortunate men who have forfeited their lives, (that is, the other prisoners condemned to die for non-sexual ‘crimes’), ‘feel a repugnance to ascending the same scaffold with you, therefore the Court order that you be executed at an earlier and distinct period. Degraded as you are, let me exhort you to devote the little time you have to live, in imploring forgiveness of that Being who is able and willing to extend mercy to the vilest sinner. It is my earnest wish that by your contrition, you may avoid that fire in an eternal world which consumed in former ages the inhabitants of whole cities, for a similar offence to yours.’

(Morning Post – 25 September 1822)

John Holland’s father, Edward, petitioned for clemency on his son’s behalf, claiming that his son was mentally deranged, but to no avail and both men were hanged. Newspapers were filled with lurid accounts of their final moments on the scaffold –

‘EXECUTION. – On Monday morning, John Holland … and William King … were executed in front of the debtors’ door of Newgate, for an unnatural crime. Holland, when on his trial, was apparently in perfect health, but on Monday morning he was little better than a skeleton, and was so weak as to be almost incapable of sustaining the weight of his emaciated frame. He has left a wife and two children, of whom he took leave on Sunday, after attending the condemned sermon. – King has been attended since his condemnation by the Rev Mr. Baker, to whose advice he paid respectful attention, but observed a sullen taciturnity till the moment of his death. – Holland acknowledged his crime, and the justice of his fate, and ever since the arrival of the warrant for his executing, his time, night and day, has been employed in loud exclamations and petitions to the Supreme Being for mercy and pardon. At a quarter before 8 o’clock, Holland was relieved of his irons. This man had a very effeminate voice, and his screams of mental anguish were most appalling. His whole frame was agonized with terror. King was brought from his cell next, and he approached the anvil, to be relieved of his irons, with the greatest firmness. At a quarter past eight o’clock the executioner said that all was prepared, Dr. Cotton commenced a reading a prayer, and in the middle of it took out his handkerchief, and gave the customary signal, the bolt was drawn, and the men launched into eternity’.

(Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette – 28 November 1822)

Arthur Martland © LGBT History Month 2025

always a good read thanks Tony

LikeLike