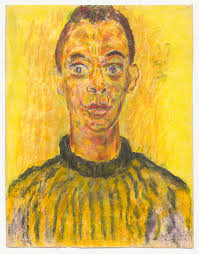

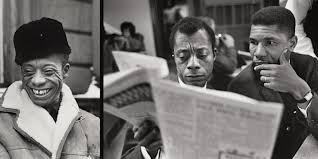

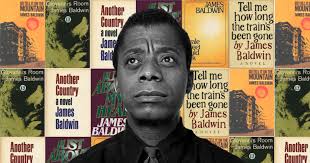

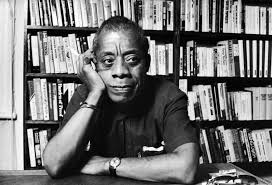

James Baldwin

James Baldwin, one of the most influential writers and thinkers of the 20th century, is remembered this year as the world commemorates the centennial birthday of The Icon – prolific author, poet, playwright, cultural critic, thought leader and activist.

Baldwin’s profound contributions to literature, social criticism and civil rights have left an indelible mark on the culture and political landscape. As we celebrate this milestone, we reflect on his enduring legacy and the relevance of his work today.

Born on 2 August 1924, in Harlem, New York, Baldwin emerged from a challenging childhood marked by poverty and systemic racism. Despite hardships, he found solace and inspiration in the written word – and so did his audiences. Baldwin’s writings have influenced generations of readers globally and continue to be foundational for navigating history, race and politics.

Baldwin’s literary achievements were only a portion of the man’s greatness. He was a prominent figure in the Civil Rights Movement and used his platform to advocate for racial equality, LGBTQ+ rights and human dignity.

Baldwin fought on behalf of all – even when those Baldwin included in his vision for freedom failed to return the favour. His was Black queer politics, and for Baldwin, there was no winning for all if some are forced by the many to lose along the way. The sooner we learn that lesson, the sooner we may collectively build a global community of people liberated from the desire to devour one another. That was his vision.

In short, Baldwin was the quintessential Renaissance man, and there are celebrations worldwide paying tribute to 100 years of the man, the myth and the legend.

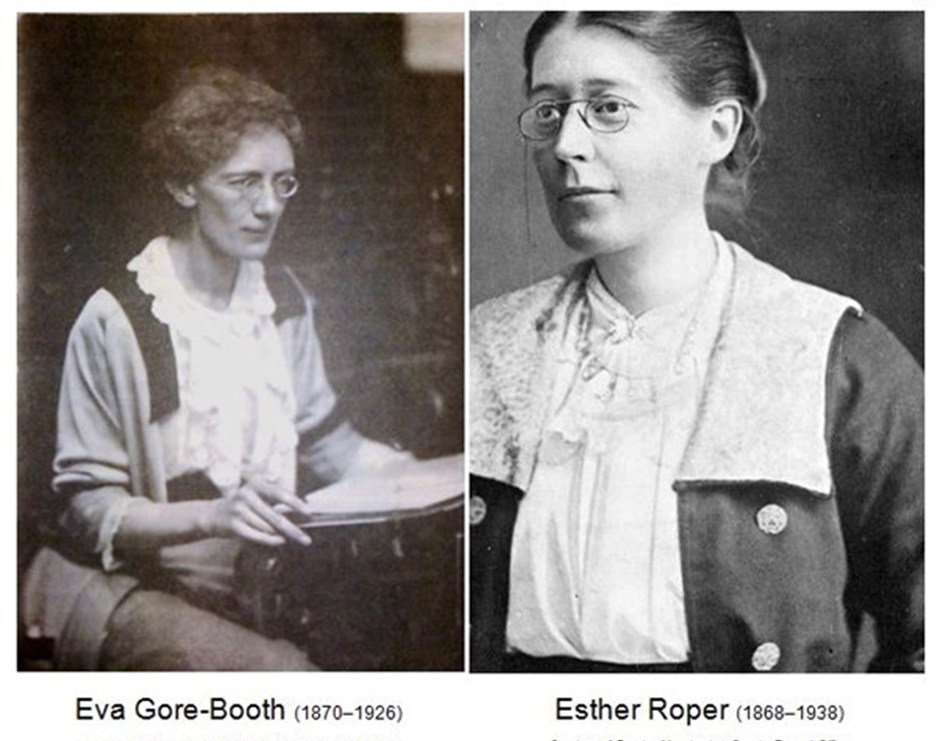

Esther Roper was born on 3 August 1868, near Chorley. She never really knew her parents, as they went to Africa to do missionary work, and left Esther with grandparents in London. They put her in a children’s home at the age of four.

When she was 18, Esther came to Manchester to study at Owens College. This was a trial scheme to see if young women were up to studying at the college level on a par with male students. Esther graduated with a 1st Class honours degree in Latin, English and Politics.

She stayed on at university, teaching and supporting female students. Esther also helped set up the Manchester University Settlement in Ancoats to give educational and cultural opportunities to local working people.

From 1893 to 1905, she was secretary of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage. She was a skilled organiser, administrator and fund-raiser, leaving the speech-making to others, but always busy working behind the scenes. She is credited with steering the movement away from focusing on middle-class women, and instead tried to get working-class women involved as well.

In 1896, she fell poorly and took a cure / holiday in Italy. There she met Irish aristocrat and poet, Eva Gore-Booth. They fell in love. Eva gave up her life of comfort and privilege to come to Manchester, where she lived with Esther in a terraced house in Rusholme.

Together, Esther and Eva worked tirelessly for women’s rights. They helped to organise groups of female flower-sellers, barmaids and coal pit-brow workers whose jobs were under attack from moral crusaders, who said such work wasn’t “appropriate” for women and would encourage “loose morals”. Esther argued that these women didn’t have a choice; they needed to keep their jobs simply to help pay the rent and feed their families. She arranged public meetings, demonstrations and delegations to lobby parliament.

Although Esther and Eva campaigned strongly for the vote for women, they didn’t support the Pankhurst’s militant tactics. They also felt Emmeline wasn’t sufficiently interested in working-class women. They were, however, very close to Christabel, who adored them.

Esther and Eva moved to London in 1913. They were pacifists who spoke out against the senselessness of the First World War, setting up the Women’s Peace Crusade to call for a negotiated peace.

In 1926, Eva fell ill with cancer. Esther was at her bedside and later wrote: “At the end, she [Eva] looked up with that exquisite smile that always lighted up her face when she saw one she loved, then closed her eyes and was at peace.“

Esther worked to preserve Eva’s memory. She edited and published a book of her poetry and had a stained-glass window celebrating Eva’s life put in at the University Settlement Roundhouse in Ancoats (the Roundhouse was demolished in 1986, by which time the window had been smashed or stolen).

Esther was campaigning for women’s rights and social justice to the end. She died in 1938, aged 69 and was laid to rest with Eva.

(Thanks to John Davies / We Grew Up in Manchester for the information)

Edinburgh’s ‘underground’ gay nightclub that a notorious cop shut down

An Edinburgh nightclub known as a meeting place for men in the city was shut down by a “decorated” policeman, after he launched what was described as a “war on homosexuality” back in the ’30s.

Nowadays, we’ve got a lot to be thankful for when it comes to LGBT+rights – though it hasn’t always been that way.

With Pride celebrations happening all summer, many will be flocking to the streets to celebrate being their authentic selves.

However in 1930s Edinburgh, people didn’t have such an opportunity and had to find other ways to meet up with like-minded people.

One dancehall had a “reputation” for serving as a meeting place for many. Maximes Dancehall, which stood on West Tollcross, was one of the many spots in the city at the time where men looking to meet up with other men would visit. It was owned by businessman Peter Ogg, who was thought to be involved in the organisation of “homosexual life in the city”.

At the time not only was participating in the sex trade illegal, but sex between men was a crime in itself.

Edinburgh copper William Merrilees, a decorated policeman at the time, found out Peter’s name through his enquiries and made it his mission to take him down. Merrilees had climbed up the ranks of the police rapidly, after joining in 1924 at the age of 26.

The then-procurator fiscal James Adair alerted Merrilees (also known as Wee Willie due to his height) to a ‘worrying’ increase in homosexual ‘offences’ which kicked off his self-described ‘war on homosexuality’. He investigated the Rosebery Boys where a small group of gay male sex workers operated out of the Rosebery Hotel in Haymarket.

He imprisoned multiple men through his search, supposedly using the “threat of prosecution of other forms of coercion”. Merrilees was satisfied by his role in the Rosebery Boys case but had now gained an appetite for rooting out homosexuals.

It was from here that he moved on to Maximes Dancehall and Peter Ogg. According to his autobiography, Ogg’s name would appear often during Merrilees’ investigations and he was led to assume Ogg was one of the “organisers of homosexual life in the city”.

Willie believes the powerful members of Edinburgh society were providing “bodies and opportunities for illicit pleasure”, with one of the meeting spots being Maximes. Apparently, Wee Willie had done extensive research and took pride in his ‘ability to affect the mannerisms of a homosexual’.

He would adopt a certain walk and a lisp, and says in his autobiography that he would convince men he was pursuing a ‘sexual adventure’. Through these techniques, he managed to get confessions from soldiers who were stationed at Redford Barracks about their involvement with “homosexual lifestyles” in the city as well as links to Peter Ogg and Maximes.

Ogg was arrested, found guilty of multiple counts of ‘sodomy’ and sentenced to two years in prison. Maximes was shut down and ultimately turned into another one of the many iterations that the West Tollcross venue has seen.

Wee Willie went on to continue his decorated career, receive an OBE, have a comic book done in his honour, and even feature in a TV special based around his life.