Angel Meadow Walking Tour

In March on a wet Wednesday, ten of us met Dean Kirby, author of “Angel Meadow: Victorian Britain’s Most Savage Slum” for a walking tour.

It was so good, another ten people joined a repeat of the tour on 2 May. Dean’s stories really brought to life the underworld of Angel Meadow, the vilest and most dangerous slum of the Industrial Revolution.

The area was considered so diabolical it was re-christened ‘hell upon earth’ by Friedrich Engels.

LGBTQIA+ Groups Growing Session at RHS Garden Bridgewater

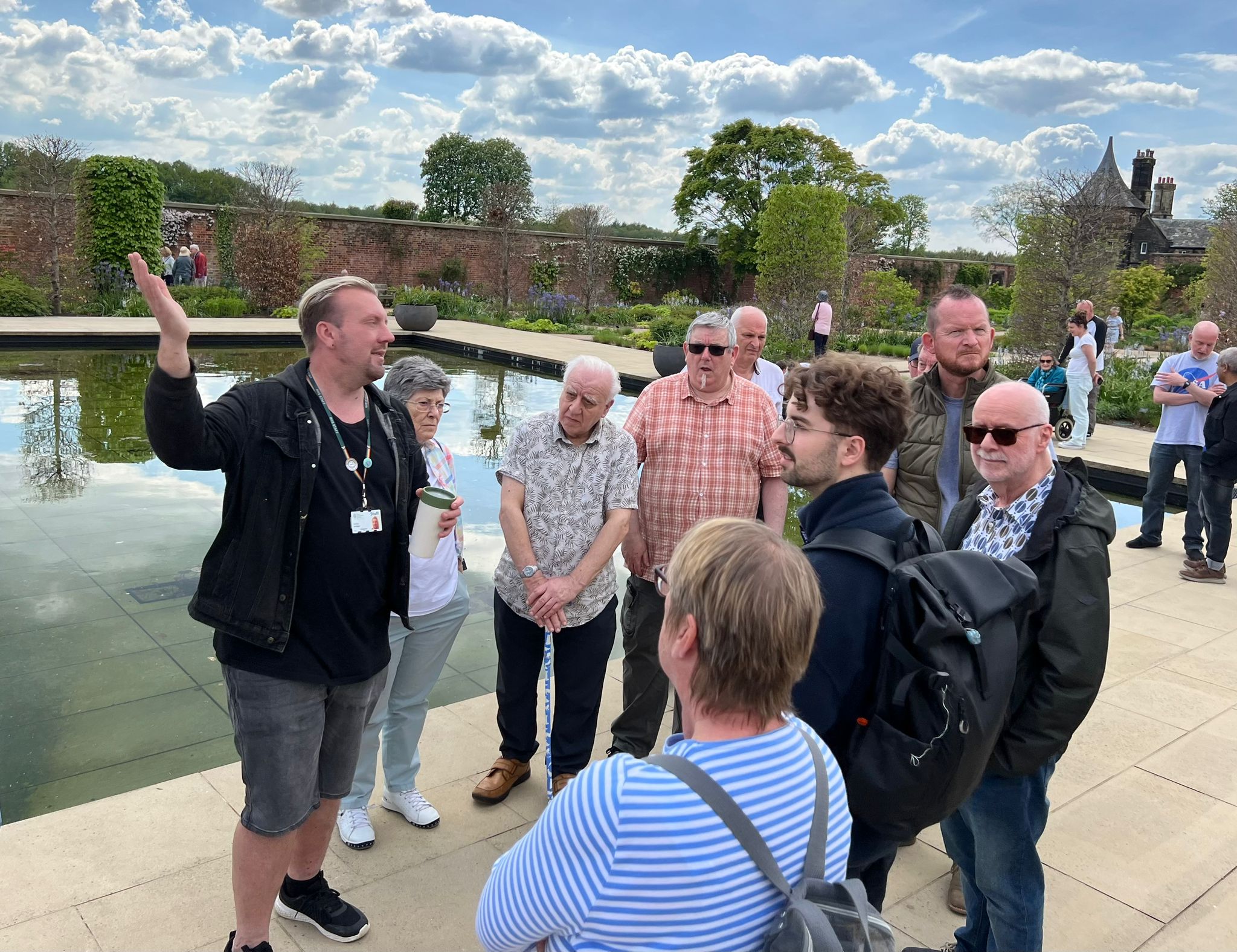

On Sunday, 5 May members of Out In The City attended the RHS Garden Bridgewater for a growing session workshop.

We had fun learning to grow some garden plants from seed and got advice on growing plants this year. We enjoyed a tour of RHS Garden Bridgewater and took away some seeds for home.

All this and cake too!

Trans+ History Week

Taking place from 6 to 12 May 2024, Trans+ History Week is an initiative celebrating the history of trans, non-binary, gender-diverse and intersex people.

Have you heard of Mary Mudge? What about Mark Weston or Michael Dillon? These are just some of the names of trans figures from British history, individuals who lived in the 19th and early 20th century and who remind us that trans stories – whether we’ve been taught about them or not – have always existed.

The delivery of transgender history has long been skewed or, at times, completely erased. Today, we can trace queer histories, cultures and communities back hundreds of years – and Trans+ History Week celebrates and recognises exactly that.

History is a powerful tool in our fight for equality and justice. So Trans+ History Week’s main objective is to inspire us to learn our stories.

To see a timeline of trans+ history click here.

Book burning

Adolf Hitler was named chancellor on 30 January 1933, and enacted policies to rid Germany of Lebensunwertes Leben, or “lives unworthy of living.” What began as a sterilisation programme ultimately led to the extermination of millions of Jews, Roma, Soviet and Polish citizens – and homosexuals and transgender people.

The sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who ran Berlin’s Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science) which opened in 1919, offered among other sexual health services, some of the world’s first medical transitions and advocated for the rights of transgender people.

When the Nazis came for the institute on 6 May 1933, Hirschfeld was out of the country. Troops swarmed the building, carrying off a bronze bust of Hirschfeld and all his precious books, which they piled in the street.

Soon a tower-like bonfire engulfed more than 20,000 books, some of them rare copies that had helped provide a history for nonconforming people. The carnage flickered over German newsreels. It was among the first and largest of the Nazi book burnings. Nazi youth, students and soldiers participated in the destruction, while voiceovers of the footage declared that the German state had committed “the intellectual garbage of the past” to the flames. The collection was irreplaceable.

How Nazi Germany Persecuted Transgender People

Images: Eric Schwab / AFP via Getty Images; Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

In autumn 2022, a German court heard an unusual case.

It was a civil lawsuit that grew out of a feud on Twitter about whether transgender people were victims of the Holocaust. Though there is no longer much debate about whether gay men and lesbians were persecuted, there’s been very little scholarship on trans people during this period.

The court took expert statements from historians before issuing an opinion that essentially acknowledges that trans people were victimised by the Nazi regime.

This is an important case. It was the first time a court acknowledged the possibility that trans people were persecuted in Nazi Germany. It was followed a few months later by the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament, formally releasing a statement recognising trans and cisgender queer people as victims of fascism. In addition to thousands of gay men killed under brutal conditions, historians believe countless transgender people and lesbian women also died.

Historians estimate that between 5,000 and 15,000 gay men were interned in camps during the Nazi’s 12-year regime. 60% of those individuals are believed to have died while imprisoned, most of whom within a year of capture.

Whilst the majority of queer people targeted during the Third Reich were gay men, the Nazi party’s broader interpretation of Paragraph 175 meant that a small portion of interned individuals were what we today would call gender-nonconforming or trans. While lesbian women were not necessarily arrested because of their sexuality, that is neither to say that some lesbian women did not end up in concentration camps, nor that the homophobia of the time didn’t impact them more broadly. Lesbian bars were shut down, book clubs squashed, communities upended.

Paragraph 175, established in 1871, existed for the first part of its history as a fairly standard sodomy law. That is it didn’t necessarily criminalise homosexuality, but rather what was considered homosexual contact – male-on-male penetration. In 1935, however, the Nazi party revised the statute such that a man could violate the law simply by looking at another man with what was deemed sexual intent. Worse still, the Nazi’s revisions to the policy also extended its maximum penalty from six months’ to five years’ imprisonment. Except in Austria, Paragraph 175 did not apply to lesbian sexuality.

Some lesbians ended up in Ravensbrück, a camp established in 1939 and the only one that was designed especially for women prisoners. Those held in Ravensbrück were typically accused of being socialists, communists, sex workers or simply “asocial” (a vague phrase that can be understood as code for lesbian.)

However, up until the past few years, there had been little research on trans people under the Nazi regime. Historians are now uncovering more cases, like that of Toni Simon.

Nazis capture Toni Simon and send her to the Welzheim concentration camp for six months. She survived and made this collage in celebration of her 70th birthday in the 1950s.

Being Trans during the Weimar Republic

In 1933, the year that Hitler took power, the police in Essen, Germany, revoked Toni Simon’s permit to dress as a woman in public. Simon, who was in her mid-40s, had been living as a woman for many years.

The Weimar Republic, the more tolerant democratic government that existed before Hitler, recognised the rights of trans people, though in a begrudging, limited way. Under the republic, police granted trans people permits like the one Simon had.

In the 1930s, transgender people were called “transvestites”, which is rarely a preferred term for trans people today, but at the time approximated what’s now meant by “transgender”. The police permits were called “Transvestitenschein” (transvestite certificates), and they exempted a person from the laws against cross-dressing. Before the “transvestite passes”, gender-nonconforming people could be subject to arrest for appearing in public in a manner that might “disturb the peace.” Under the Republic, trans people could also change their names legally, though they had to pick from a short, preapproved list.

The Eldorado was one of the most popular and notorious queer venues in Weimar Germany. Here, a group of women and gender-nonconforming people pose by the bar.

The surprising hospitality attributed to the Weimar period is often exaggerated. Hirschfeld was attacked several times, subverting the idea that the pioneering sexologist’s pro-LGBT+ views were largely accepted at the time. He even had a bomb thrown at him one time.

In Berlin, LGBT+ people published several magazines and had a political club. Signs of cracks in the facade of early Berlin’s tolerance begin to show when considering the number of gay magazines circulating at the time. These numerous titles did not reflect a flourishing publishing industry; they constituted a reaction to censorship. The queer press would put out one magazine for a little while and when it would end up on the banned list, they would change the name.

Some glamorous trans women worked at the internationally famous Eldorado cabaret.

Trans people flock from around the world to visit the Institute. Four trans activists at the First International Conference for Sexual Reform.

The rise of Nazi Germany destroyed this relatively open environment. The Nazis shut down the magazines, the Eldorado and Hirschfeld’s institute. Most people who held “transvestite certificates,” as Toni Simon did, had them revoked or watched helplessly as police refused to honour them.

That was just the beginning of the trouble.

Nazi banners hang in the windows of the former Eldorado nightclub. Landesarchiv Berlin / US Holocaust Memorial Museum

‘Draconian measures’ against trans people

In Nazi Germany, transgender people were not used as a political issue in the way they are today. There was little public discussion of trans people.

What the Nazis did say about them, however, was chilling.

The author of a 1938 book on “the problem of transvestitism” (Ein Beitrag zum Problem des Transvestitismus by Hermann Ferdinand Voss) wrote that before Hitler was in power, there was not much that could be done about transgender people, but that now, in Nazi Germany, they could be put in concentration camps or subjected to forced castration. That was good, he believed, because the “asocial mindset” of trans people and their supposedly frequent “criminal activity … justifies draconian measures by the state”.

Otto Kohlmann (born 15 February 1918) was forcibly sterilised on 30 September 1935 at age 17 in Hadamar for their transmasculinity and sleeping with alleged sex workers. The Kohlmann family tried to use lawyers to get them out with no success. Otto escaped from Hadamar on no fewer than three occasions between 1936 and 1938 but was caught each time. They reportedly sent love letters to female detainees and refused to follow instructions from the guards. They were pathologised due to “always wearing a man’s shirt as a blouse; when it was taken away from (them), (they) howled and wailed.” Officials finally sent them to Ravensbrück in 1940, where they were interned until liberation in 1945.

They died in 1956 at age 38 from tuberculosis.