Trans+ History Week

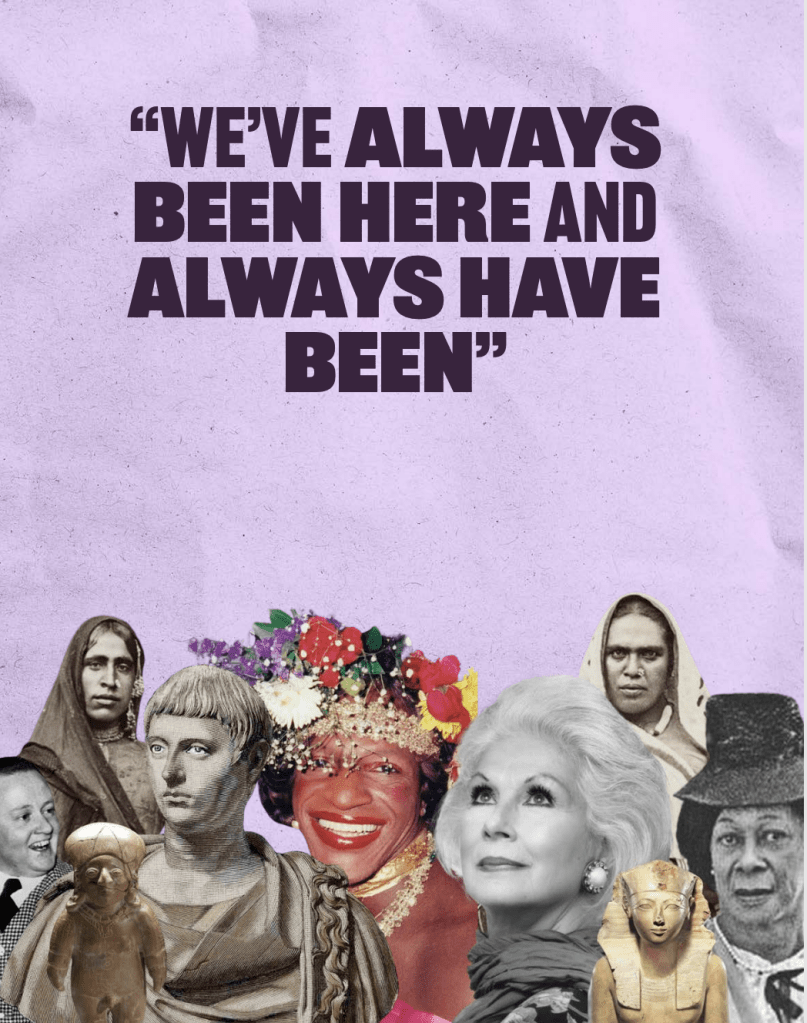

In May 2024, QueerAF started the first Trans+ History Week, observed for the week beginning 6 May 2024, to celebrate the history of transgender, non-binary, gender-nonconforming, and intersex people. The organisation hosted billboards across the UK with the slogan “Always been here. Always will be.”

They got the idea after learning about the Nazi book burnings that targeted trans texts on 6 May 1933 after a raid on the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin.

This year Trans+ History Week will be celebrated from 5 May to 11 May 2025. During the week we make space for, platform and share our rich history. A history which is as long as all of human life.

See timeline for more information.

Eli Erlick

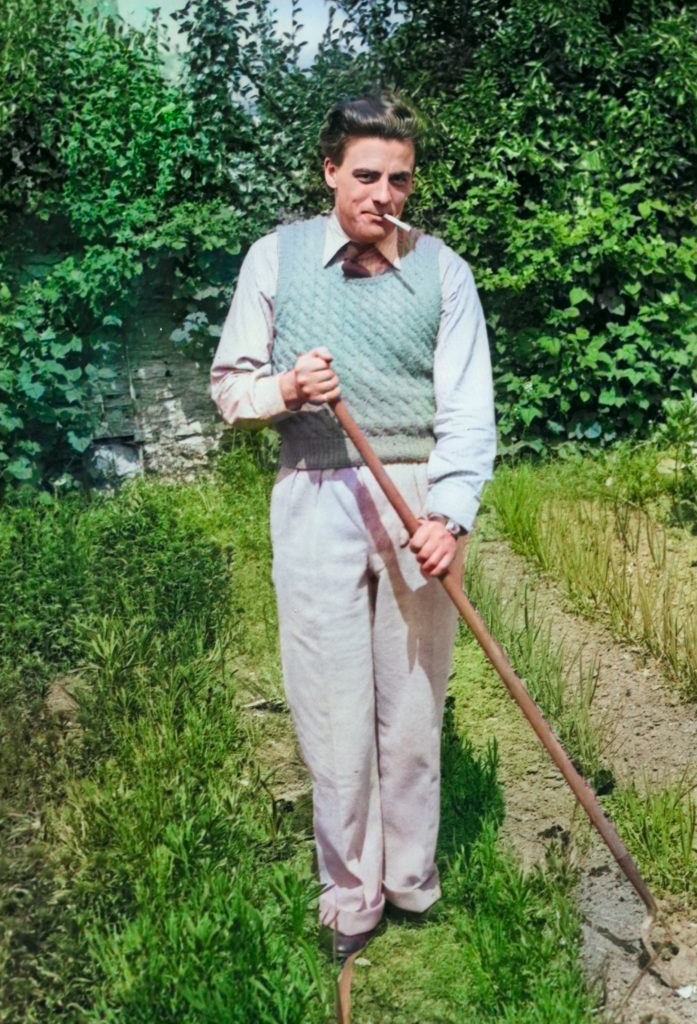

About a year ago, frustrated with the “erasure of trans history” and continued anti-trans narratives, Eli Erlick began writing a history book.

It spotlights underreported trans stories from 1850 to 1950, including some experiences that haven’t been told in 120 years.

Unfortunately, a lot of history isn’t just withheld on purpose by the far-right but also by academics and publishing companies that want to maintain the intellectual property.

She said, “So I wanted to do something very public, very accessible and very understandable to the mainstream.”

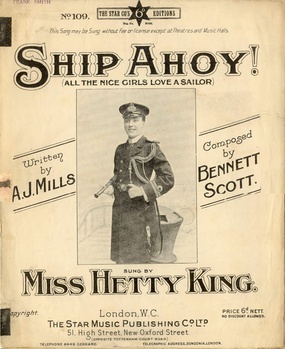

As part of her work, Eli colourises historical black and white images. As she explains: “We know from past social movements, particularly the civil rights movement, colourisation brings the subject closer to the viewer. We think of subjects who don’t have photos or have black and white photos as lesser, as in the past, as of a different time, era or culture – even when this could have only been 50 years ago.”

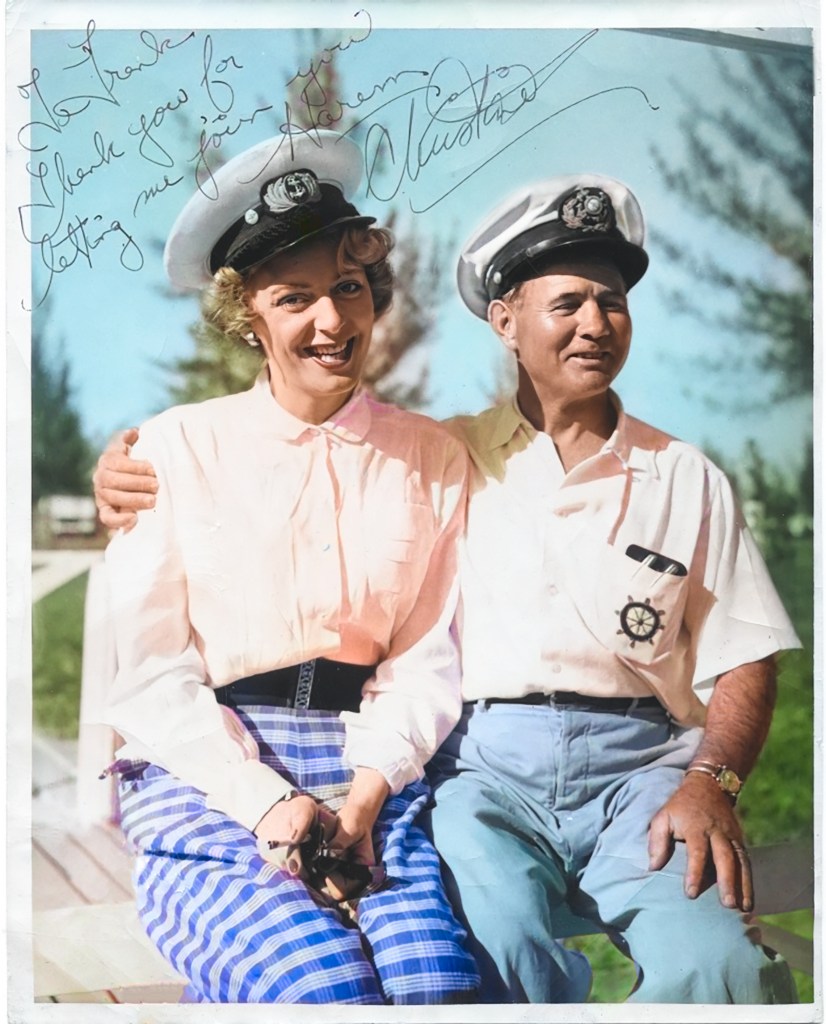

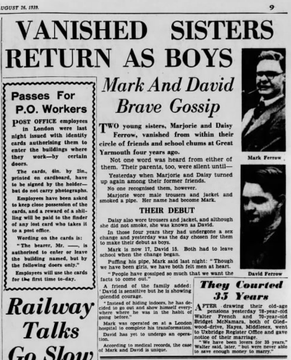

Eli has posted images of world champion athlete Mark Weston, who transitioned in 1936, and Christine Jorgensen, who was the first trans person to become widely known in the US for having gender-affirmation surgery.

“I was colorising trans photos and it reminded me of star athlete Mark Weston, who transitioned in 1936. It’s as if he was erased from the history books. He was one of the world’s top athletes and Britain’s #1 women’s shot putter for six years. His brother Harry was also trans!”

Through her research, Eli has found that trans people were treated relatively “well” in the 19th and 20th centuries – especially compared to how the community is “currently being demonised as a sort of contagion”.

“Trans people used to be treated, at worst, as a curiosity or even a medical breakthrough, and it was generally positive,” she says.

She adds: “It’s clear that right now we have a significant problem in reporting and also in queer and trans historiography.”

“We shouldn’t have to produce evidence of our own history,” she says. “Yet, we are forced to … colouring these images helps remind viewers that trans people – real people – have always existed and will continue to thrive no matter how much we are attacked.”

Karl Kohnheim – Businessman, Advocate, Trans

What did it mean to transition in Weimar Germany?

Karl Kohnheim (sometimes referred to in documentation as ‘Katharina T’) was the first person to receive a German Transvestitenschein, the official government documentation that allowed dressing in affirming clothes (literally transvestites pass). Karl fought to be legally recognised as a man for over 15 years before he was given his pass; it took 8 years to receive a notice to allow his style of dress, and he was never allowed to legally change his name.

What can we learn from Karl Kohnheim?

We can’t be erased. Trans+ people have always been resilient and have always had to fight for their identities. Even when the Nazis targeted the first trans+ clinic in the world, even when they burnt our medical records and outlawed our very existence, we didn’t disappear.

Magnus Hirschfeld was one of the strongest trans+ allies in the Weimar period. He founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee) and the World League for Sexual Reform. His Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Research) was the site of the first sex reassignment surgery. Hirschfeld was not transgender himself, but he felt that trans+ people deserved more dignity than they were offered in society. The incoming fascist regime targeted him for those views as well as the fact that he was Jewish and gay.

Hirschfeld also gives us the opportunity to reflect on those we choose to put on a pedestal. He pushed trans+ rights forward significantly in his time, but he was deeply racist, heldstrong views on how eugenics could be used positively in society, and had complicated power dynamics in relationships with quite young men. It’s important that we are careful about the people we invest in and recognise that no person is a monolith. We can’t excuse Hirschfeld’s horrific and dangerous ideas just because he was supportive of trans+ folks.

Campaigners urge Greater Manchester Police to apologise for alleged history of homophobic policing

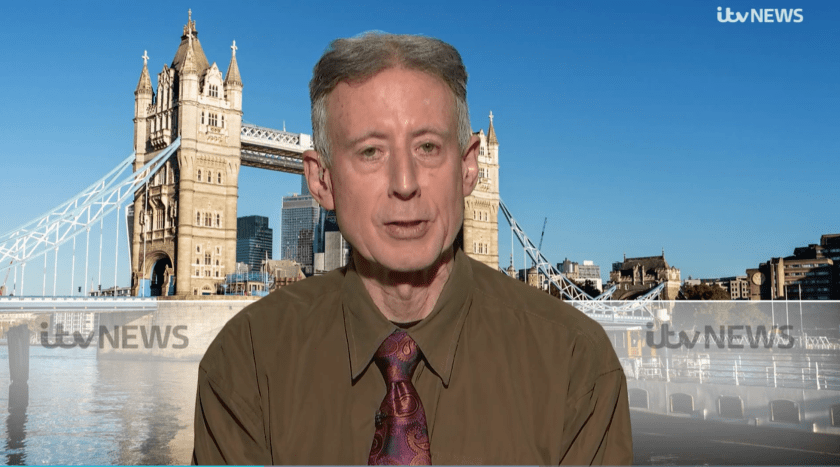

The Peter Tatchell Foundation has written to the Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, and the Chief Constable Stephen Watson asking for “a formal apology for decades of abusive, homophobic policing that devastated the lives of LGBT+ people.”

The Foundation sent the letter on 16 April, and though it acknowledged Manchester’s more inclusive and supportive policies today, it condemned the force’s historic persecution of LGBT+ people as “some of the most vicious and aggressively homophobic in Britain.”

Citing the tenure of Chief Constable James Anderton in the 1980’s, they claim that he openly denounced gay men as “swirling around in a cesspit of their own making” and orchestrated a campaign of harassment, entrapment and humiliation.

The Foundation also says that victims were beaten, arrested for kissing, and outed in the press—leading to prison, fines, job losses, evictions and suicide attempts.

The Foundation is not asking the police to apologise for enforcing now-repealed homophobic laws, but to say sorry for the “abusive and often unlawful manner” in which these laws were enforced.

“Raiding gay birthday parties, using homophobic slurs and harassing and bashing people outside gay pubs—these tactics would never be acceptable today,” said Tatchell.

“So far, 21 UK police forces have apologised for similar past wrongs, including the Metropolitan Police, Police Scotland and Merseyside Police. Their apologies have been followed by new LGBT+ action plans, including the appointment of LGBT+ community liaison officers and the establishment of homophobic hate crime hotlines. These apologies and new supportive LGBT+ policies have much improved relations between the police and the LGBT+ community.”

“Mayor Burnham and the Chief Constable were not responsible for the past homophobic abuses,” Tatchell said, “but as people with oversight of the police, they have the power—and duty—to help make amends. A formal apology would be an important act of healing. It would boost in trust and confidence in the police, and encourage more LGBTs to report hate crimes, domestic violence and sexual assaults.”

A GMP Spokesperson said: “The GMP of today is proud to serve and protect all communities in our dynamic city-region. We strive to engage with all our diverse communities to understand their non-recent experiences and ensure they feel policing of today is doing more to listen to concerns and work together to make Greater Manchester a safer place for everyone.”

Theatrical Double Standards

Sheridan Morley was an English author, biographer, critic and broadcaster. He was the official biographer of Sir John Gielgud and wrote biographies of many other theatrical figures he had known, including Noël Coward.

In this article from The Spectator dated 5 May 2001, Sheridan Morley looks back on changing public and police attitudes towards gay actors.

For me, it all began with Jimmy Edwards – a revered actor and comedian, a war hero badly burned at Arnhem, a lord rector of Aberdeen university, and for 11 years the beloved, irascible Pa Glum of Take It From Here on BBC Radio. In the late 1970s he was “outed”, and it was revealed to a somewhat surprised world that Jim, he of the tuba and the handlebar moustache, was in fact also a lifelong homosexual.

“Out of the closet?” he once boomed indignantly at me in a pub near Broadcasting House. “Of course I didn’t come out of the bloody closet. They broke the bloody door down and dragged me out against my will.” Soon after that Edwards settled in Australia, and far too soon after that he was dead at only 68. I am not suggesting the outing killed him, but it certainly made it harder for him to find work in Britain. It is at least arguable that his life and career as well as that of many others were shortened by the strain of some very unwelcome publicity.

As late as the 1980s, British public and private intolerance of homosexuality was still more than enough to ruin careers and lives, or at least to do them considerable damage; the television star Peter Wyngarde and Leonard Sachs of The Good Old Days were just two of maybe a dozen actors whose careers never really came back from court cases involving cottaging, even though there was no question of the involvement of minors, or indeed anyone other than consenting adults.

The tragedy was that for many of these men, often born into a 1920s world where the memory of Oscar Wilde was still strong, there was no possibility of coming to any terms with what even they still thought of as a criminal offence, and a deep cause of familial and sometimes also marital shame.

To this day, the stigma can still kill: in May 1998, the former soccer star Justin Fashanu committed suicide a month after a warrant was issued for his arrest on charges of sexual assault against a teenager in America – charges denied in his suicide note. Ironically, in that same week, the first “gay walking tour” of Soho was announced, and clearly there was a double standard already established: suggestions of homosexuality did little harm, for instance, to the careers of Kenneth Williams or Frankie Howerd, because their public personae were long established as gay, even though they both resolutely refused to tell the truth and Williams once threatened to sue me for inadvertently, in a theatre annual, publishing nothing more overtly “damaging” than a picture of him on a beach in Morocco with Joe Orton and his killer Kenneth Halliwell.

If however your career depended on any kind of a romantic image, whether as an actor or a pop star, the danger of alienating audiences was still all too real and, amazingly, remains so to this day, more than 100 years after the death of Wilde.

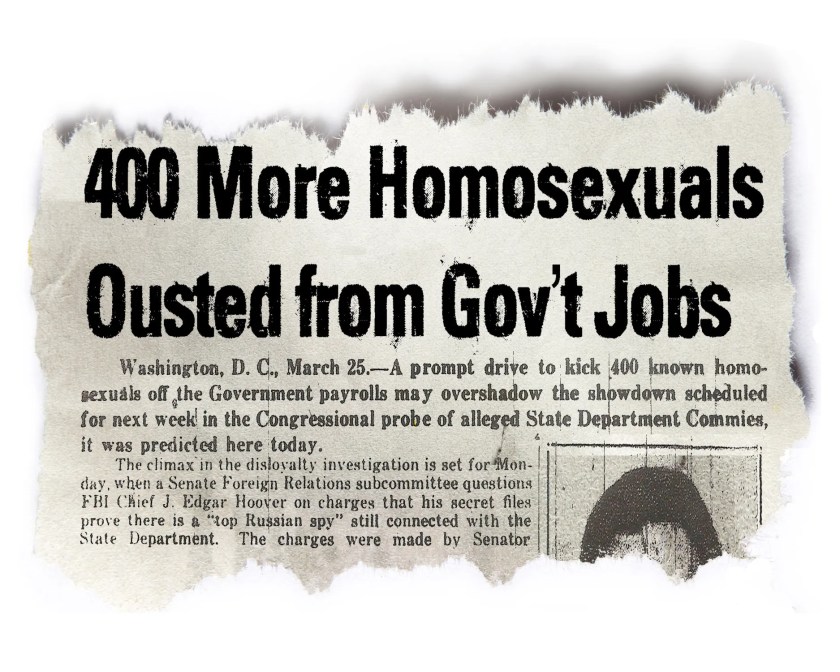

I believe, having researched in some detail the arrest of Sir John Gielgud in 1953 with police who recall the case, that the witch hunt of homosexual actors in the years after the second world war was as firmly established over here, and did as much damage to lives and careers, as that of the simultaneous witch hunt of American actors and writers by the McCarthy Committee on UnAmerican Activities in Hollywood.

Indeed there is a direct transatlantic connection. In the aftermath of the Burgess and Maclean defection to Moscow, the FBI had strongly requested that the Home Office make every effort “to weed out homosexuals from British public life”, since they could clearly form a security risk at a time when the Cold War was still at its height. Accordingly, one of Scotland Yard’s top-rated officers, Commander E.A. Cole, was seconded for three months to Washington to examine in detail the anti-communist campaign in America, and to see whether there were useful lessons to be learnt for the ongoing war on homosexuality in Britain.

The commander rapidly reached the conclusion that witch hunts were apt to be counterproductive, but 1953 was in many ways the watershed. It was of course the year of the Coronation, of Everest, of a “New Britain” not unlike the one envisaged almost half a century later by Tony Blair. It was however still more divisive; in every area of public life, there was a group of reactionaries who believed that, with “a slip of a girl” newly on the throne, Britain was in imminent danger of going to the dogs, and that therefore the sooner Victorian values could be reimposed, harshly if necessary, the better for our long-term moral health. But now for the first time there was an equally powerful group of younger movers and shakers who saw in the Coronation changeover the chance finally to drag Britain into the 20th century and line her up with more liberal European neighbours such as France and Italy, where homosexuality among consenting adults had long been decriminalised.

The battle which started in that year dragged on for about 20 more, and it took many hostages. Some playwrights, among them Terence Rattigan and Noel Coward, followed Isherwood and Auden into exile, choosing places in the sun such as Bermuda and Jamaica where their discreetly homosexual lives could be pursued without fear of the police or press. Others chose to remain in Britain, despite the evidence of increasing intolerance.

Birthdays