Saddleworth Museum and Art Gallery

A group of us travelled eleven miles by bus from Manchester to Saddleworth, an area primarily known for its textile industry heritage, picturesque moorland scenery and charming villages.

After a lovely lunch at The Caffe Grande Abaco, we headed for the Museum and Art Gallery. Founded in 1962, the museum is housed in the remains of the 19th century Victoria Mill. Saddleworth was a major centre for cotton spinning and weaving during the Industrial Revolution.

Annie Kenney was born in Springhead in Saddleworth and became a prominent figure in the suffragette movement.

She left school at age 13 to work in the cotton mill. Annie was the first local woman trade union representative, and inspired by Christabel Pankhurst she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union. This group was the first to use militant tactics to bring attention to the rights of women.

The militant campaign began in Manchester in 1905, when Christabel Pankhurst and Annie were arrested at The Free Trade Hall. Annie was an excellent speaker and her working class background meant that she was understood by many working women. She was regularly put in prison and in 1913 was sentenced for three years. Annie was released because she was on hunger strike but was not allowed to speak at meetings. She refused to accept this and attended meetings in disguise and was often re-arrested.

It was a very hot day – 28 degrees – and a mint chocolate chip ice cream was in order before heading back to sunny Manchester. More photos can be seen here.

Seafront statue of Benjamin Britten given approval

A life-sized statue of Benjamin Britten will soon be unveiled after plans for the seafront project were given approval.

The bronze sculpture of the composer as a boy will be installed opposite 21 Kirkley Cliff Road, Lowestoft, where he was born on 22 November 1913.

The Britten as a Boy project was co-founded by teacher and artist Ruth Wharrier, who has been granted permission by East Suffolk Council to move forward with the creation.

“The project has always been about promoting aspiration for generations of children of Lowestoft to dream big just as Benjamin Britten did 100 years ago,” she said.

“Our simple message of looking ahead has also inspired many adults within our community, including those recovering from domestic and substance abuse.”

The possibility of a statue being made became a reality after members of East Suffolk Council, Lowestoft Town Council and Kirkley People’s Forum raised £110,000.

It was designed by sculptor Ian Rank-Broadley, who has described Britten – who died in 1976 – as a “genius”.

‘Successful children of Lowestoft’

“It’s really important we recognise people of our town who succeeded, councillor Peter Byatt said.

“I hope this is going to be the beginning of revisiting those successful children of Lowestoft.”

Zeb Soanes, vice chairman of the project, has previously said he, too, hoped the piece would act as an inspiration for young people in the town.

“Our idea of depicting [Britten as a child] is to really inspire children that whatever you want, if you work hard, it is achievable,” he said.

The Hidden Case of Sir Ewan Forbes, the Transgender Baronet

In 1968, a new name was placed on the United Kingdom’s Official Roll of the Baronetage: Sir Ewan Forbes, the 11th Baronet Forbes of Craigievar. A quintessential Scottish gentleman, Ewan was a perfect fit for his new role. He was a caring country doctor, a doting husband, a sportsman who excelled in riding, shooting, fishing, and Scottish dance, and whose ancient, rather eccentric aristocratic clan had deep ties to the British royal family.

“His grandfather had been an intimate friend of Queen Victoria; his mother was a close friend of Queen Mary; his father was aide-de-camp to King George V. And their castle, Craigievar Castle (now owned by the National Trust for Scotland), is only 30 miles away from Balmoral,” says Zoë Playdon, emeritus professor of medical humanities at the University of London and author of The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes: And the Unwritten History of the Trans Experience.

As outlined in academic Zoë Playdon’s 2021 book – soon to become a TV mini series – Forbes was born into a deeply privileged family with ties to the British royals. Evidence points to the fact that Ewan himself entertained the royal family, who shared his deep love of horses and the country.

But despite his deep privilege, Ewan’s journey was not an easy one. “Like most trans people, Ewan learned from an early age to be resilient, imaginative, and courageous in facing the challenges that the world threw at him. He’s really very inspirational,” Playdon says. Ewan’s biggest battle would lead to an invasive court case which led to his ascendence as Baronet Forbes of Craigievar. The case would be shrouded in secrecy for years, and Playdon believes its implications set trans rights back decades.

Ewan was born on 6 September, 1912, and christened Elizabeth Forbes-Sempill. Elizabeth was the third child and second daughter of John Forbes-Sempill, 18th Lord Sempill and 9th Baronet of Craigievar, and Gwendolen, Lady Sempill. From an early age, the compassionate, open-minded Gwendolen knew that her third child, who she called Benjie, was different. Ewan eschewed stereotypically girlish pursuits and clothing, loved tramping through the Highlands at Craigievar Castle, and worshipped his elder brother, William, an aviation pioneer. She had Ewan homeschooled and let him live as his authentic self on the family’s massive estates.

“Gwendolen, the Lady Sempill, was remarkable for her time, and I think a real inspiration to parents today with trans children,” says Playdon. “Like them, she recognised the insistence, persistence, and consistence of Ewan’s understanding of himself as a boy, in spite of his birth-assigned sex. She supported his social transition … and she found him affirmative medical support as soon as it became available.”

In an intolerant time, options were limited. “Everyone realised my difficulties,” Ewan once recalled, per The Daily Telegraph. “But it was hard in those days to know what to do.”

But Gwendolen would not be deterred. According to Playdon, Gwendolen took a teenage Ewan to visit experts across Europe, disguising their adventures as a grand tour. Ewan was given treatments, almost certainly including testosterone. “I found it necessary to shave,” Ewan recalled, “because I had quite a lusty growth of hair on my chin and cheeks.”

There is no doubt these visits to doctors working with intersex and transgender patients were not only a result of Gwendolen’s tireless efforts, but also the family’s immense privilege. “Ewan’s family had the wealth and connections required to access the new affirmative trans medical support that was being developed in Europe in the 1920s,” Playdon shares.

However, the family’s illustrious connections and high profile also had downsides.

“His father was a stickler for social form, so that whenever they were in the public eye, Ewan was obliged to dress up as a girl for society photographs – including being required, as a matter of family honour, to dress up as a debutante to be presented to the queen,” Playdon notes. “This must have been horribly embarrassing for him, but he saw it as his duty and somehow got through it.”

Indeed, Ewan later recalled these events as making him feel “like a bird that had had its wings clipped.” After being presented to his mother’s good friend Queen Mary in 1930, he went to London debutante balls “under protest and duress.” Afterwards, he recalled, “I made my escape and I never went back.”

Instead, Ewan threw himself into Scottish culture, forming the popular “Dancers of Don” dance troupe, in which he often took the male leads. After his father died in 1934, Ewan almost exclusively wore the male Scottish kilt and worked the family’s extensive estates. In 1939, he started medical school at the University of Aberdeen. A year after his beloved mother died in 1944, he began work as a family doctor in the Scottish village of Alford, near the family seat of Craigievar Castle.

Jovial and kindly, with a special knack with children, Dr Forbes-Sempill was known to go to any lengths to help his patients. In 1947, he bought the 3000-acre Brux Lodge and settled into his role as a beloved villager who could be found judging country dances and reciting ancient Doric poems.

But in 1952, Ewan’s insular, protected life would be thrust into the national news. Ewan had fallen in love with his kind and gentle housekeeper Isabella “Patty” Mitchell and wanted to marry her, despite the fact that gay marriage was illegal. “I felt the right to have my own wife and my own house, and take my place as other ordinary individuals,” Ewan recalled.

Ewan decided to take the brave step of having his birth certificate amended to the gender he had always known he was. Though surprising to modern readers, residents of the United Kingdom at the time could amend their birth certificates, as long as doctors agreed the initial assignment had been a mistake. As a respected member of the Scottish medical community, Ewan was easily able to obtain the necessary permissions. Legally, he was now a man, and free to marry Patty.

“It was very confusing to us children,” Ewan’s great-niece later said. “Suddenly Auntie Elizabeth was Uncle Ewan. But we all adored him.”

The townspeople of Alford reacted in much the same way. “The doctor has been telling us for some time of his intended announcement. We admire his courage in taking this step.”

The national press took a more sensational view, aware that Ewan now could inherit the Forbes baronetcy, which passed to the next male heir. “It has been a ghastly mistake,” Ewan told one reporter. “I was carelessly registered as a girl in the first place … The doctors in those days were mistaken … I have been sacrificed to prudery, and the horror which our parents had about sex.”

According to Playdon, Ewan was unable to make his daily rounds on foot because of reporters blocking his way. In an effort to avoid the press, Ewan bought a Land Rover, after Princess Margaret told him that her father had acquired one.

On 12 October, 1952, Ewan and Patty were married in a secretive nighttime ceremony at Brux, with members of both their families present. “It seems likely, too, that at least one member of the Royal Family was at Ewan’s wedding to Patty, since the wedding was held very privately,” Playdon says. “Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, in their 20s, were both on holiday at Balmoral. Still today, those who know will not say precisely who all the guests were!”

The village of Alford was not as shy in celebrating the new couple. “His patients had clubbed together to buy him and Patty handsome wedding gifts,” Playdon writes in The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes. “A special dance had been composed in honour of Ewan and Patty, called ‘The Doctor’s Waddin,’ to celebrate the occasion … Finally, the minister who had married them gave Ewan an encomium: ‘No matter how deep the snow, no matter how high the river or wind, the doctor is always there when we need him.’”

Ewan and Patty settled into a quiet, contented life. In 1955, Ewan quit his practice to focus on running his estate, where he raised prize-winning cattle and entertained neighbourhood children. But this peaceful idyll was shattered in December 1965, when his brother William, 19th Lord Sempill and 10th Baronet Forbes, died. Although the barony went to William’s daughter Anne, the baronetcy was to be passed to the next male heir, Ewan.

Well aware of Ewan’s history, his cousin John Forbes-Sempill, a film producer, put in a claim for the baronetcy, and would declare Ewan “of the female sex in the physical, anatomical, physiological, and genetic meanings of that term.”

According to Playdon, Ewan, terrified that a court case would destroy his life and invalidate his marriage, struck a deal with his cousin, giving him what was left of the family estates. In return, John reportedly agreed to not pursue the baronetcy.

But John had no interest in giving up his claim, and he soon enlisted Ewan’s estranged older sister Margaret to strengthen his claim. Margaret was a strong-willed eccentric who ran a successful pony stud from her home of Druminnor Castle, alongside her life partner, Joan.

According to Playdon, Margaret was heavily in debt, and John agreed to pay her debts if she went against her brother. On 8 March, 1966, she wrote a letter to John’s lawyer, outing Ewan:

“I always regarded Dr Ewan as my sister … She went through the phase (as I did myself and so many girls do) of wanting to be a boy,” she wrote. “She went to parties, dances, etc., and was presented at Court in 1929 or 1930. She had her periods regularly just the same as any other girl … That will show her on whose side I am on.”

After emotional conversations with Ewan and his doctor, Margaret soon regretted her betrayal, and agreed to testify in court that she had been mistaken. But that was never to be. On 28 October, 1966, Margaret was killed in a car crash. Ewan now had to rely solely on his own wits and the help of the medical community to fight John.

What followed was a flurry of claims, counter claims, analyst reports and a demeaning medical examination meant to prove or disprove Ewan’s manhood. After a medical test proclaimed Ewan a female with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (probably due to his longtime use of hormones), the doctor took matters into his own hands. Ewan claimed to have biopsied a recently descended testicle and provided a tissue sample that was, indeed, someone’s testicular tissue, which he submitted to the court.

On 15 May, 1967, the opposing sides assembled for a four-day hearing presided over by Lord Jack Hunter of the Scottish Court of Sessions. Experts, friends, and colleagues were examined – as were Ewan and Patty, who were subject to an extremely demeaning line of sexual questions. Unable to discredit the bogus testicular sample, and swayed by the tests determining Ewan’s psychological sex to be male, in early 1968, Hunter ruled narrowly in favour of Ewan, writing he was “a true hermaphrodite in whom male sexual characteristics predominate”.

The proceeding received little media attention, due to Ewan’s powerful connections. “Undoubtedly, Ewan’s aristocratic background kept his case out of the press. Cecil King, (chairman of several prominent newspaper groups), had an estate that shared boundaries with the Craigievar estate, and Ewan’s sister-in-law, Cecilia, Lady Sempill, asked King to keep the case out of the newspapers,” Playdon says.

But the Home Secretary’s decision to officially grant Ewan the title in late 1968 did make the news. Headlines like “Former Girl Now N S Peer” and “‘Elizabeth’ becomes baronet” titillated the public, leading Ewan and Patty to retreat further into their sheltered life at Brux.

Playdon also believes (though some dispute her conclusions) that Ewan’s case influenced the outcome of 1970’s Corbett v Corbett. This was a divorce case where aristocrat Arthur Corbett sought to annul his marriage to transgender model April Ashley (covered extensively in the fascinating 2025 documentary Enigma). Dismissing the phycological factors that Hunter prioritised, this case established that sex was defined by chromosomal, gonadal, and genital factors, and since gay marriage was illegal, the marriage was annulled.

With this devastating decision, transgender rights, including trans people’s ability to correct their birth certificates, were swept away (in 2004, the UK granted transgender people full legal recognition). Playdon believes this was an overcorrection of Ewan’s case, enacted to protect the interest of primogeniture, where noble titles (and until 2013, the monarchy) are inherited by the eldest male heir.

“I’d known how trans lives had changed through April’s case,” Playdon said. “But I’d never known why that change had happened – what the motive had been for removing trans civil liberties and consigning trans people to the outermost fringes of society. It was very shocking to see the evidence that it was done to protect the political interest of a tiny minority of royal and aristocratic men whose inheritances were (and except for the King, still are) regulated by primogeniture.”

Ewan’s case, which could have upset the precedent set by Corbett v. Corbett, was also successfully hidden from public view. According to Playdon, after she learned of the case’s existence, it took two years – and direct pressure from the Home Secretary – for the Scottish Records Office to reveal the case and send over a transcript.

As anti-trans hate intensified in the coming decades, Ewan continued his quiet life at Brux. An elder at the Presbyterian Church, he became more old fashioned and dogmatic in his older years, but never lost his sense of humour. Ewan rarely discussed or even acknowledged his transgender status. Instead, he became a keeper of memories, publishing his idyllic memoir The Aul’ Days in 1984 and a book about the “Dancers of the Don” in 1989. “He truly was an unforgettably gentle, kind, and charming man,” journalist Moreen Simpson, who interviewed him in the 1980s, recalled, “parts of whose life had been the stuff of nightmares.”

Sir Ewan Forbes, the 11th Baronet Forbes of Craigievar, died on 12 September, 1991. His beloved Patty followed in 2002. Their insistence on living an authentic life reverberates today in a world of increasing anti-trans rhetoric. “There is a view, propagated by anti-trans voices, that trans people are new to this decade,” says Playdon. “And as Ewan’s story tells us, nothing could be further from the truth.”

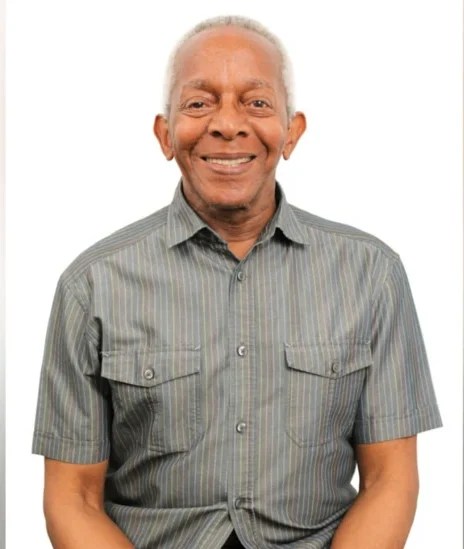

Being a Champion Against Ageism

Pauline is a passionate advocate for LGBT+ and older people’s rights in Bury, Greater Manchester, and beyond. Since retiring, Pauline’s creativity has flourished through powerful poetry that challenges ageism and inspires change. Watch and listen to the latest poem, ‘Being a Champion Against Ageism’.