Gay News

Gay News was a fortnightly newspaper founded in June 1972 in a collaboration between former members of the Gay Liberation Front and members of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality. At the newspaper’s height, circulation was 18,000 to 19,000 copies.

Amongst Gay News’s early “Special Friends” were Graham Chapman of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, his partner David Sherlock, and Antony Grey, secretary of the UK Homosexual Law Reform Society from 1962 to 1970.

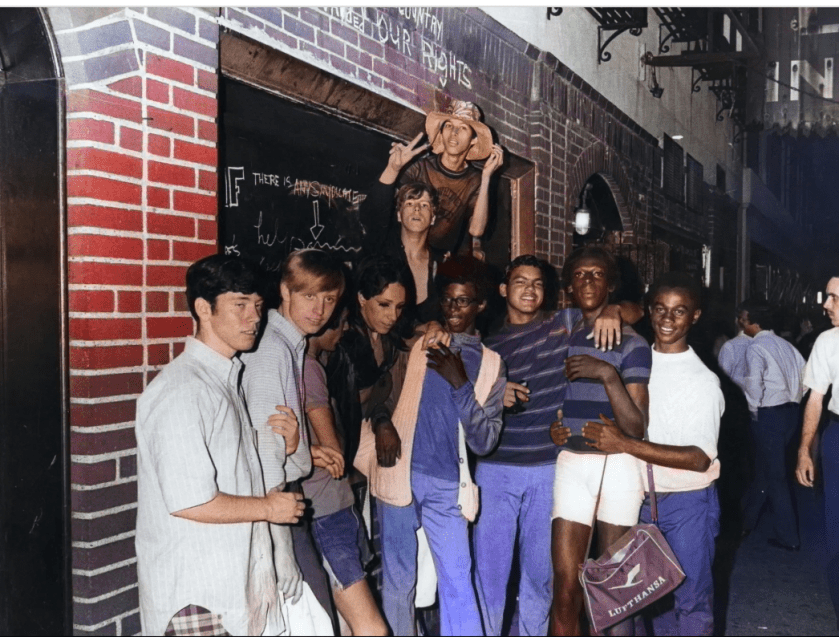

Sex between men had been partially decriminalised for males over the age of 21 in England and Wales with the passage of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. After the Stonewall Riots in New York in 1969, the Gay Liberation Front spread from the United States to London in 1970. Gay News was the response to a nationwide demand by lesbians and gay men for news of the burgeoning liberation movement.

The paper played a pivotal role in the struggle for gay rights in the 1970s in the UK. Although essentially a newspaper, reporting alike on discrimination and political and social advances, it also campaigned for further law reform, including parity with the heterosexual age of consent of sixteen, against the hostility of the church which treated homosexuality as a sin, and the medical profession which treated homosexuality as a pathology. It campaigned for equal rights in employment (notably in the controversial area of the teaching profession) and the trades union movement at a time when left politics in the United Kingdom was still historically influenced by its roots in its hostility to homosexuality. But it also excavated the lesbian and cultural history of past decades as well as presenting new developments in the arts.

Gay News challenged the authorities from the outset by publishing personal contact ads, in defiance of the law; in early editions this section was always headlined “Love knoweth no laws.”

In the first year of publication, editor Denis Lemon was charged and fined for obstruction, for taking photographs of police behaviour outside the popular leather bar in Earls Court, the Coleherne pub.

In September 1973 Gay News, in conjunction with the Gay Liberation Front, recognised that they were receiving a large volume of information calls to their offices. Accordingly, they put out a call for a switchboard to be organised. Six months later, on 4 March 1974, the London Gay Switchboard (now Switchboard – LGBT+ Helpline) was formed. Gay News alongside Switchboard and the Health Education Council went on to hold the first open conference on HIV/AIDS in Britain on 21 May 1983. At this conference Mel Rosen, of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, New York, declared “I hope you get very scared today because there is a locomotive coming down the tracks and it’s leaving the United States.”

In 1974, Gay News was charged with obscenity, having published an issue with a cover photograph of two men kissing. It won the court case.

The newspaper was featured in the 1975 film Tommy.

In 1976 Mary Whitehouse brought a private prosecution of blasphemy (Whitehouse v Lemon) against both the newspaper and its editor, Denis Lemon, over the publication of James Kirkup’s poem The Love that Dares to Speak its Name in the issue dated 3 June 1976. Lemon was found guilty when the case came to court in July 1977 and sentenced to a suspended nine-month prison sentence and personally fined £1,000.

When all totalled up, fines and court costs awarded against Lemon and Gay News amounted to nearly £10,000. After a campaign and several appeals the suspended prison sentence was dropped, but the conviction remained in force. The case drew enormous media coverage at the time. In 2002 BBC Radio 4 broadcast a play about the trial.

Gay News Ltd ceased trading on 15 April 1983.

Queer Fest

Join us on 21 June, for Queer Fest, a full day of celebrations of LGBTQI+ literary, arts and culture. There will be stalls from a variety of artists and writers, as well as drop-in badge making with Sarah-Joy Ford. On the day of Queer Fest we also are pleased to announce the opening of a brand new exhibition, “I’ve had enough of secrets” by Steven Appleby.

Please see above for more information about the event, including scheduled Q&As with Steven Appleby and Malcolm Garrett as well as Matt Cain with David Catterall; spoken word performances; Polari Bible Readings with Jez Dolan; figure drawing with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

Admission is free. Some events will be bookable.

With Love, Mr Gay (by Josh Val Martin)

Saturday 21 June – 7.30pm

The Box @ The Met, Market Street, Bury BL9 0BW

“Dear Mr. Gay, if you move my bin again, I will get an ex-mercenary to destroy you … from flat 2.”

This (real) letter was blue-tacked to my flat’s front door, and thus sparked a neighbourhood feud over both my sexuality, and the placement of the blue bins.

Determined to find peace, and not let the conflict consume me, I sought advice and interviewed experts: a dog trainer, a historian, a Middle East peace negotiator and, of course, my Auntie Clare.

With Love, Mr Gay is my true story, featuring cabaret, comedy, interviews and showtunes, as I’m accompanied by the personification of a laughing Buddha statue from B&M, who acts as my unlikely spiritual guide.

Join us on our heartfelt and hilarious mission to find fabulous ways of ending deeply personal battles – even when the idea of peace seems impossible.

Funded by the Bury LGBTQI+ Forum and Bury Pride as part of the of Bury LGBTQI Literary Festival.

Book tickets here – £12 / £10 concessions

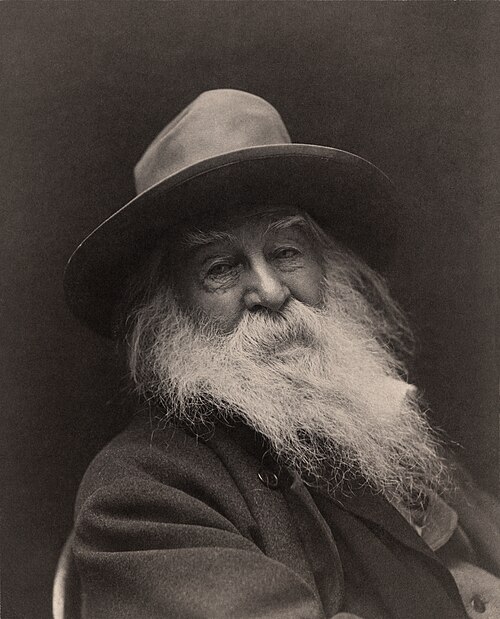

Robina Asti

Robina Asti

Born in Manhattan on 7 April 1921 and raised in Greenwich Village, Robina Asti was a trans woman, WWII veteran and aviation pioneer.

She spent much of her adult life residing at 1175 York Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Though she transitioned in the 1970s and lived publicly as a woman for over 40 years, she only became more widely known when she was in her 90s, after she successfully challenged discriminatory federal policy.

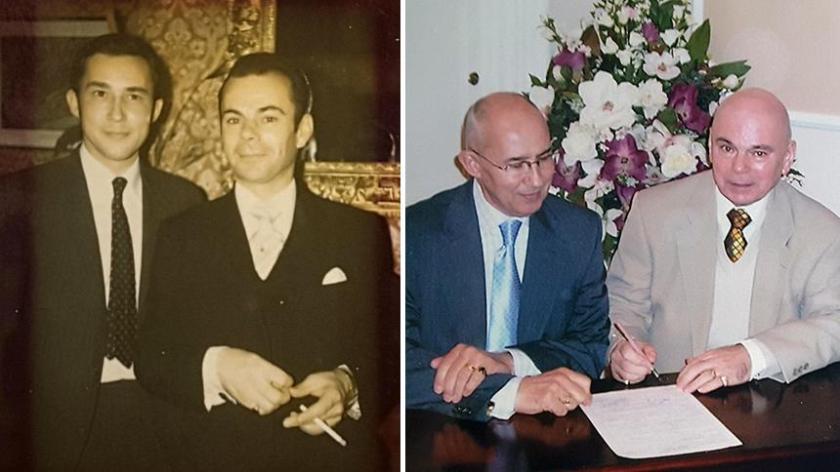

In 2012, following the death of her husband, artist Norwood Patten, Asti applied for Social Security survivor benefits. Despite holding legal documents identifying her as female, including her pilot’s license, the Social Security Administration (SSA) denied her claim, citing her gender at birth as a problem.

Represented by Lambda Legal, Asti appealed and won, prompting the SSA to revise its policies for transgender spouses nationwide. Her case became a landmark moment for transgender rights and was documented in the short film Flying Solo: A Transgender Widow Fights Discrimination.

Asti was also a decorated WWII Navy pilot and lieutenant commander, who flew reconnaissance missions over the Pacific and who later worked as a test pilot.

After the war, she became a successful mutual fund executive before transitioning in the mid-1970s, a decision that cost her high-powered finance career but allowed her to embrace her identity more fully. She then took a job as a makeup artist at Bloomingdale’s and later became chair of the Hudson Valley chapter of the Ninety-Nines, an international organisation of female pilots.

In 2019, Asti co-founded the Cloud Dancers Foundation, which advocates for elderly trans individuals. In July 2020, Asti was recognised by Guinness World Records as the oldest active pilot & flight instructor at age 99.

She passed away in 2021 in California, shortly before her 100th birthday. Through her many accomplishments later in life, however, Asti helped shift public policy and broaden recognition of transgender people – especially elders – within both LGBTQ+ communities and US legal frameworks.

Birthdays

Q. You know what winds up bigots more than a photo of a Pride-themed train?

A. A photo of a Pride-themed train passing a stretch of water so you actually see two Pride-themed trains.