What did the High Court say about Trans people and the use of loos?

Here is an accurate summary of the High Court judgement dated 13 February 2026 in the case brought by Good Law Project to challenge the lawfulness of the interim guidance (previously) issued by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) regarding single-sex spaces, cutting through polarised rhetoric.

The judgment does not establish that trans people are banned from any spaces. Instead, it clarifies a nuanced legal framework:

Workplaces must provide “suitable and sufficient” single-sex facilities OR single-person lockable rooms.

Employers must provide facilities separated by biological sex or single-user lockable rooms. But they can (and often must) provide additional facilities beyond the minimum to avoid discriminating against trans staff.

Public services (shops, cafés, etc) have no legal requirement to provide single-sex facilities at all.

Service providers can choose mixed/unisex facilities, single-sex facilities (if proportionate to a legitimate aim), or both. They are not compelled to exclude trans people.

Single-sex facilities

Cease to be legally “single-sex” if used according to gender identity rather than biological sex.

This is a definitional point – not a ban. Providers can still allow trans-inclusive use; they just can’t label it “single-sex” while doing so.

Proportionality is everything: even where single-sex provision is permitted, it’s only lawful if “a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim” (Equality Act 2010, Sch 3).

Blanket exclusions of trans people may fail this test and constitute unlawful discrimination on grounds of gender reassignment (paras 66-67, 71).

No requirement to police biological sex: The judge explicitly rejected the idea that employers must “police” toilet use “person by person and day by day” as “divorced from reality” (para 40). Good faith policies are sufficient.

Trans-inclusive facilities may be lawful: The judge was notably less certain than the EHRC that allowing trans women in women’s facilities while excluding other men would automatically constitute sex discrimination against men.

It depends on circumstances and whether it amounts to “less favourable treatment” (paras 57-62). This undermines claims of a strict “either everyone or no one” rule.

Dignity obligations remain: Providers must ensure trans people aren’t left with no appropriate facilities. Expecting all trans people to use only facilities matching their biological sex may not be proportionate (para 66).

The guidance itself encouraged providing mixed-sex or single-user facilities alongside single-sex ones (points [3c] and [3d]).

The judge:

- warned against “unyielding ideologies” and noted the law is “more nuanced” than public debate suggests (para 25-27);

- criticised framing rights as “trumping” each other in a “zero-sum game” when the Equality Act actually balances multiple protected characteristics;

- called it “bizarre” to speak of legal “rights” to particular toilets – urging providers to be guided by “common sense and benevolence” rather than rigid rules (para 27).

The court found that the way the EHRC revised the guidance was “opaque and very unsatisfactory” – changes weren’t clearly flagged to readers (para 92).

But crucially: the court did NOT find the guidance legally inaccurate or unlawful in substance

The court rejected arguments that workplace regulations only govern physical provision of facilities without governing their use (the purpose is clearly to provide private space separated by biological sex for “reasons of propriety”).

Noted that concerns about gossip when using accessible facilities, while sincerely held, don’t necessarily amount to legal discrimination (para 73).

Bottom Line for Trans People

- You are not banned from using facilities matching your gender identity.

- Service providers can provide trans-inclusive facilities – they’re not legally prohibited from doing so.

- Employers must avoid unlawful discrimination on grounds of gender reassignment when making facility arrangements.

But facilities designated as “single-sex” (for Equality Act purposes) must align with biological sex – though providers can choose not to designate as such.

The legal test is always proportionality: blanket exclusions may be unlawful; thoughtful, context-sensitive arrangements are required.

The judgment ultimately affirms that equality law requires nuanced, fact-sensitive application – not rigid rules.

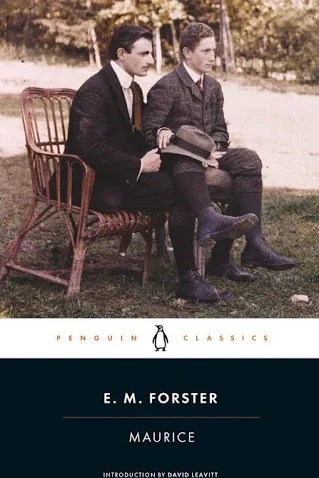

Maurice

He wrote a love story between two men with a happy ending in 1914 – then locked it in a drawer for 57 years. He died one year before the world finally read it.

E M Forster was already a celebrated author in 1913 when he began writing a novel he knew he could never publish. He had written A Room with a View and Howards End, books that made him famous, books that examined English society with wit and precision.

But this new novel was different. This one was about him.

Maurice tells the story of a young man who falls in love with his Cambridge classmate, Clive Durham. When Clive eventually rejects him, Maurice finds love with Alec Scudder, a working-class gamekeeper. And here’s what made it revolutionary: they run away together. They choose each other. They get a happy ending. In 1914, that ending was unthinkable.

This wasn’t ancient history. This was the era of Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment still fresh in memory, of men arrested and jailed for “gross indecency”, of lives destroyed simply for loving someone of the same sex.

Homosexuality was a crime punishable by up to two years of hard labour. The law wouldn’t change until 1967 – and even then, only partially. Men lost their careers, their families, their freedom. Some were chemically castrated. Some took their own lives rather than face exposure.

Oscar Wilde had died in exile in 1900, destroyed by the very society Forster moved through. The message was clear: if you were a man who loved men, your story could only end in tragedy, shame or silence. But Forster refused to write that ending.

When he finished Maurice in 1914, he showed it to a handful of trusted friends. Their responses were mixed. Some were moved. Others warned him never to publish it. One friend told him it was “too dangerous.”

Forster typed a note and attached it to the manuscript: “Publishable – but is it worth it?” Then he put it in a drawer and locked it away.

For the next 56 years, Maurice existed only in typescript, read by a small circle of Forster’s closest confidants. He revised it occasionally, updating details, refining scenes. But he never published it. He couldn’t. Not while his mother was alive.

Lily Forster lived until 1945, dying at age 90. Forster had lived with her for most of his life. She was domineering, possessive, and completely unaware – or wilfully ignorant – of her son’s sexuality. Forster couldn’t risk her discovering the truth, couldn’t bear the scandal it would bring to her.

After her death, Forster was more open with friends, but still not with the world. He was 66 years old when his mother died, too old to rebuild a life as an openly gay man, too entrenched in a society that would reject him.

He had other secrets, too. In 1930, Forster met Bob Buckingham, a 28-year-old policeman. Forster was 51. They fell deeply in love – or something like it. Their relationship was physical and emotional, documented in letters that reveal Forster’s longing and devotion.

Then, in 1932, Bob married a woman named May Hockey. The relationship didn’t end. Instead, it transformed into a complicated triangle. Forster remained close to both Bob and May for the rest of his life, often visiting them, sometimes causing tension. It was love, compromise, and quiet heartbreak all at once.

Forster lived in the shadows – loving Bob, writing privately, achieving public success while hiding his true self.

In 1954, something happened that reminded Forster just how dangerous those shadows were. Alan Turing, the brilliant mathematician who had helped crack the Enigma code and save countless lives during World War II, was arrested for “gross indecency” after his relationship with another man was discovered. He was convicted. Given a choice between prison or chemical castration, he chose the latter.

In 1954, Turing died of cyanide poisoning. The official verdict was suicide.

Forster knew Turing. He knew what the law could do. He knew that Maurice, with its defiant happy ending, was not just a love story – it was an act of rebellion. But still, he didn’t publish it.

He left instructions: the novel could be published after his death. Only then would it be safe. Only then could it exist without destroying him.

E M Forster died on 7 June 1970, at age 91. He had lived through two world wars, had written masterpieces that were taught in schools, had been celebrated and honoured. But he died without ever seeing Maurice in print.

In August 1971, one year after Forster’s death, Maurice was finally published. The timing was extraordinary. The Stonewall riots had occurred in 1969, igniting the modern LGBT+ rights movement. The world was changing, slowly but undeniably. And into that changing world came a novel written 57 years earlier – a novel that said, quietly but firmly: You deserve to be happy. You deserve love. You deserve an ending that doesn’t break you. The response was overwhelming.

Gay readers around the world found themselves in Maurice’s story. For many, it was the first time they’d seen their own experience reflected in literature – not as tragedy, not as cautionary tale, but as love worthy of celebration.

Letters poured in from people who had lived in hiding, who had believed their only options were loneliness or shame. Maurice told them something different. It told them they could choose each other. They could run away together. They could be happy.

In 1987, the novel was adapted into a film by Merchant Ivory, bringing Forster’s hidden masterpiece to an even wider audience.

But Forster never knew any of this. He died believing the world might reject his truth, might judge him, might destroy what little peace he had built. He locked away the most honest thing he ever wrote – a love story that said happiness was possible – and lived his life in the quiet spaces between what was said and what was felt.

E M Forster spent 57 years protecting Maurice. He protected it from the law, from scandal, from a society that would have punished him for writing it. And in doing so, he gave future generations something rare: a story that ends not with death or despair, but with two men choosing each other and walking into the greenwood together, free.

He lived in the shadows. But he left behind a light. And that light – 57 years delayed, one year too late for him to see – has been shining ever since.

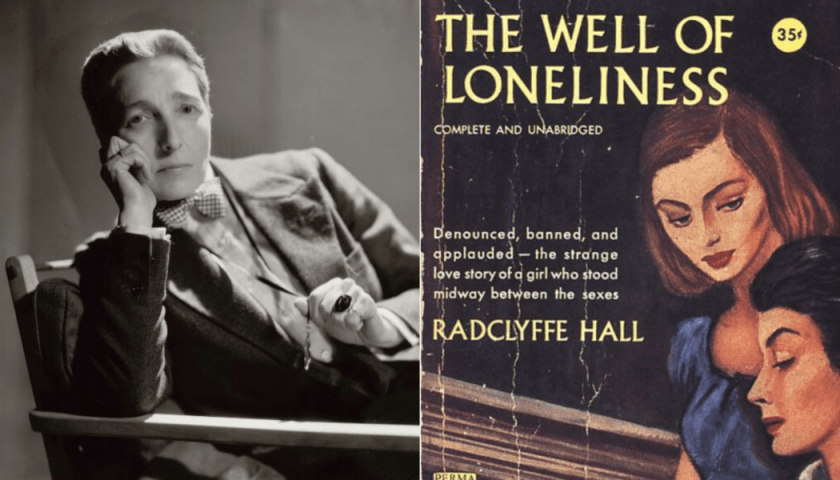

Inside the censorship campaign against this 20th century lesbian novel

Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was the target of a mass censorship campaign in the early 20th century.

First published in 1928, the semi-autobiographical novel follows a so-called “inverted” woman named Stephen, who enjoys the company of other women and dressing in men’s clothes. It is considered the first widely read novel about the lesbian experience written in English.

Shortly after it was published in the UK, James Douglas used his position as editor of the Sunday Express to call for the book to be banned to “prevent the contamination and corruption of English fiction.”

The Well of Loneliness was accused of violating the Obscene Publications Act of 1857. While the novel did not contain explicit content, its exploration of queer themes was said to “deprave and corrupt” the minds of those who read it.

During the obscenity trial, judges refused to hear expert testimonies about the artistic merits of the book from authors like Virigina Woolf and E M Forster, claiming they were irrelevant. The book was ruled to be “obscene libel” and was ordered to be destroyed.

But the book’s legal challenges unfolded quite differently in the US. After the novel was accused of violating the 1873 Comstock Act, the publishers’ lawyer Morris Ernst successfully argued that lesbianism was not inherently obscene or illegal, resulting in the case being dismissed.

Hall would not live to see her novel back on shelves in the UK once the Obscene Publications Act was amended in 1959, but its legacy lives on as a seminal work of lesbian literature that is still read and analysed today.

LGBT+ History Month Party in Cross Street Chapel

Thursday, 19 February – 2.00pm – 4.00pm – Free

featuring Joe Cockx (from the Golden Age Big Band) performing Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra and Andy Williams.

There will also be a raffle and buffet.

RSVP for catering purposes.

Really interesting and informative articles Tony. Many thanks

LikeLike