Could an Openly Gay Queen or King Rule the UK?

Imagine a scenario from a possible future: A king and queen leave the throne to their first born son or daughter. This heir to the throne is married to someone of the same sex.

Would the gay king or queen’s spouse have a royal title? Would their child be heir to the throne? Current law doesn’t have answers to those questions.

In 2013 Queen Elizabeth II came out (obliquely) in support of LGBT rights. Last year King Charles III attended the launch of “Open Letter” – the memorial for UK LGBT+ service members, showing support for the LGBT+ communities for the first time.

Turns out there have been many royals in the past that had tongues wagging over their rumoured gay ways:

William II

William II was an effeminate medieval king who never married. Was he an unsung hero of the LGBTQ community? William II might actually have been trans since he often favoured women’s clothing.

Richard I

Richard the Lionheart, often portrayed as gay in films (notably by Anthony Hopkins in The Lion in Winter), was a “gay icon”. Richard reportedly shared a bed with King Philip II of France.

Edward II

This royal’s same-sex infatuations were so well-known that Christopher Marlowe’s 1593 play Edward the Second included the king’s fraught relationship with Piers Gaveston, a close adviser and member of his court. Derek Jarman’s 1991 film Edward II was based on the play and went a lot further than Marlowe, with gay sex and oodles of homoeroticism.

James I

Although married, King James is often remembered as bisexual, and members of his court called him “Queen James.” In honour of the king, who spearheaded an English-language translation of the Bible, there’s a modern version that expunges all the antigay references titled Queen James Bible.

Queen Anne

Queen Anne’s friendship with Sarah Churchill – founder of the Churchill-Spencer dynasty, which produced Winston Churchill and Diana, Princess of Wales – was likely very close. The power-hungry Churchill blackmailed Anne by threatening to reveal their passionate letters and accused the queen of playing favourites with women in her court with whom she was sleeping.

Prince George

Prince George had three older brothers, but a scandalous string of affairs would have likely prevented him from ascending the throne anyway. Letters from Noel Coward indicate he and George were lovers, though the playwright was only one of several male lovers the prince reportedly took before his death in a plane crash at 39.

Princess Margaret

The wild younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II, Princess Margaret scandalised the royal family when she divorced her husband in 1978. Allegations of drug use and lesbian affairs appeared in the book Margaret: The Last Real Princess and the British TV movie The Queen’s Sister. The documentary Margaret: The Secret Princess also included claims of Margaret’s bisexuality.

The Brisbane Suburb of Herston

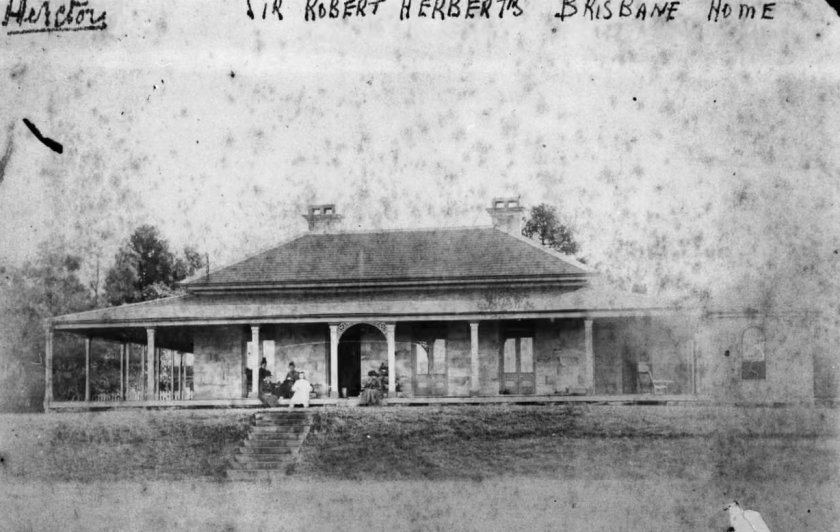

Herston is a name alluding to the state’s first premier and the man believed to be his lover.

Today the story would be unremarkable: two gay men, migrants from England, give their Queensland home a portmanteau of their last names.

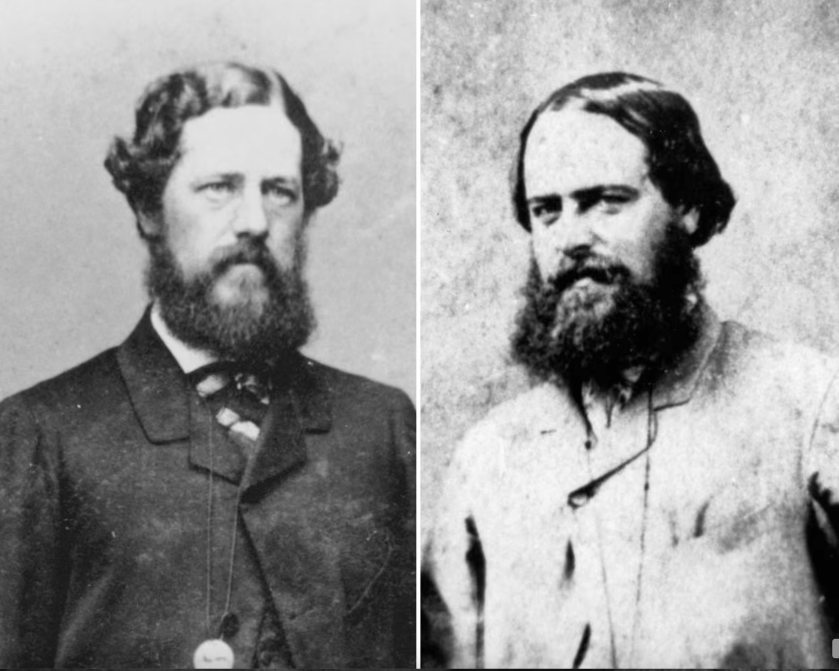

But in 1859, these two men, Robert Herbert and John Bramston, were the new state’s first premier (then called colonial secretary) and one of his attorneys general.

The name, Herston, was later used to name the modern suburb that covers the area. Gay historians argue that the long-forgotten history of Herston should finally get the recognition it deserves.

Herbert and Bramston met at Balliol College, Oxford, in the 1850s, and shared rooms there and in London.

Herbert never married and had no children.

In an 1864 letter to his sister, Herbert explained that marriage would risk “being wretched”, for a chance “of a little possible additional happiness”.

“It does not seem to me reasonable to tell a man who is happy and content, to marry a woman who may turn out a great disappointment,” the letter reads.

There must be a lot of gay men today who have explained it that way to their sisters and mothers.

Herbert held his position until February 1866 and returned to England shortly afterwards, where he lived until his death in 1905.

Bramston also returned briefly to England, but was back in Queensland by 1868, and married Eliza Russell in Brisbane in 1872. He died in Wimbledon in 1921.

Herbert’s government showed an unusual degree of sympathy for gay men. Queensland was the first state in the country to remove the death penalty for the offence of male sodomy. New South Wales did not do so for two decades.

Their relationship was doubly unlawful, doubly secret, because of Herbert’s influential position.

But we need to be careful about celebrating people in the past who lived closeted lives, because we only know a limited amount about them.

Homophobia in politics escalated by the conservative government of Russell Cooper, part of a desperate attempt to distract from revelations of corruption in cabinet and the police, He said a Labour government would bring a “flood of gays crossing the border from the Southern states”. There was even a proposal to extend the state’s laws to cover women for the first time.

In 1989, Queensland police laid some of Australia’s last charges under anti-gay laws. In 2017, the state government apologised and quashed a century and a half of recorded convictions.

Queensland’s first openly gay MP, Trevor Evans, was elected in 2016, 157 years after Herbert took office.

Although the Herston home is long gone – Herbert’s name lives on, but more prominently in far north Queensland, which boasts a Herbert river, a Herbert range, the town of Herberton and the federal electorate of Herbert. In 1975, the Queensland Place Names Board approved the official naming of the Brisbane suburb as Herston.

Shameful fact: There are still 64 countries in the world where homosexuality is illegal.