Golden Age Big Band

Twenty of us travelled to the John Alker Club, near Flixton, for an afternoon of Golden Age Big Band music plus Bingo and Afternoon Tea.

The term “Golden Age Big Band” refers to the period in American music history, roughly from the early 1930s to the late 1940s, when big band swing music was at its most popular. This era is characterised by the rise of large ensembles, often featuring prominent bandleaders like Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Duke Ellington, whose music dominated radio airwaves and dance floors.

There were 17 musicians in the band and the conductor doubled as singer. There were some standards such as Glenn Miller’s “In The Mood” as well as more obscure tunes, and we had a thoroughly enjoyable time.

More photos can be seen here.

Jonathan Blake

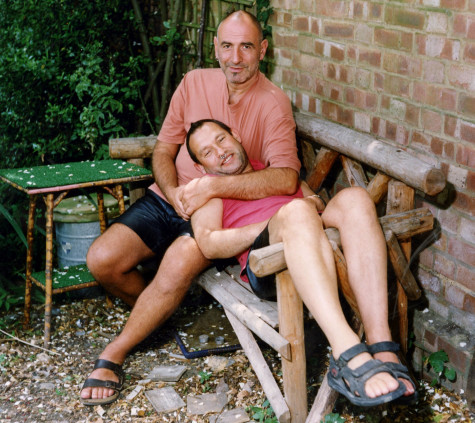

Jonathan Blake (born 21 July 1949) is a British gay rights activist. In 1982, he was told that he had just months left to live – now 76 today – he shares his groundbreaking story about his HIV diagnosis.

Jonathan Blake was just 33 years old when he became one of the first people in the UK to be diagnosed with HIV. Little did he know that after receiving what was then considered to be a “death sentence”, he would still be living a happy and healthy life at 76.

His experiences in the 1980s, along with the LGBTQ+ community which he was a part of, have since inspired both film and TV projects, including the 2014 film Pride. The film sees British actor Dominic West play Jonathan in a retelling of his work as a member of the group Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners.

Jonathan reflects on the moment he first received the harrowing news that he had contracted what was, in 1982, an unknown virus. He shared: “I was told I had a virus. There is no cure. You have between three and nine months to live … I was winded and just kind of numbed by it.”

He recalled the days leading up to his diagnosis and how he felt as though every single lymph node in his body had started to grow. After silently struggling with his mobility, Jonathan booked himself in with a GP. It was then that he was sent to hospital, where they did a biopsy and he was left waiting for a few long days.

He shared: “Two days later they came back, having done the biopsy, and they’d given me this news, that I had this virus, with three to nine months to live, and palliative care was available when the time comes. And then, after having been completely floored, they said that I could go home.”

“I mean, it was really frightening”, he continued. “And I just decided that what was in front of me was actually so horrendous that I was going to take my own life, but I didn’t know quite how I was going to do it”.

The tragic diagnosis sent him, at just 33, into isolation. The lack of information around HIV at the time meant he feared passing the virus on to others through the air. “I would forever go to the gay bars in the East End because I needed to be with people,” he said.

“But I would stand in the darkest corner and send out all the vibes to say ‘don’t come near me people’ because what are you going to say? I felt like a modern-day leper because I just assumed that it was airborne. You know, it was never explained that the only way you can pass it on is by blood and fluids, none of that.”

It was when he was at his very rock bottom that Jonathan found hope in a group of like-minded people where “everyone was welcome”. With an interest in activism and politics he spotted a tiny advert in a magazine called Capital Gay in 1983 calling on people to join the Gays For a Nuclear-Free Future in a CND campaign.

He said: “I just thought, this is going to be my re-entry into society. I’m going to join that because what the little advert said was ‘everybody welcome’, and I just thought, ‘well, that includes me’.”

This small decision changed the trajectory of Jonathan’s life as it was here that he met late partner Nigel Young. Not only that but his work with LGSM created a legacy away from his diagnosis, for his work helping under-represented groups, which in this case was a Welsh mining town.

Written by Stephen Beresford and directed by Matthew Warchus, the film Pride features a character based on Jonathan, played by Dominic West. The creation of the project helped him to reconnect with old friends and relive those spectacular years of activism while he was secretly fighting for his life.

He recalls meeting the actor who would play him in the movie. It was the day before that he got the call asking him to meet the mystery actor and classic Jonathan, welcoming everyone he comes into contact with, thought “it’s just enough time to make a lemon drizzle cake.”

Jonathan said: “So the next day arrives, the doorbell goes, I open the door, and this man thrusts out his hand and introduces himself as Matthew Weiler, the director. And over his shoulder I see McNulty from The Wire. And at that point I realised that it was Dom West. I was aware of him because I’ve watched The Wire and loved it.”

Growing up in Birmingham before making the move to London later in his life, Jonathan knew from an early age he was gay. “I already knew that I was attracted to men,” he explained. “And I had already sussed out that that wasn’t acceptable.

“You know, this wasn’t something that you could just rush home and shout about as such. At an early age if I couldn’t be found the headteacher would say ‘if you go and look where Bert is, you’ll find John’. He was the caretaker and I just followed him around. You know, pheromones, infatuation, what have you.”

The stigma that came along with HIV in the 1980s was something that didn’t help the problems he already faced as a homosexual man. During the first appearance of the virus, there was a widespread misconception that HIV and AIDS were solely diseases that affected gay men and it was this that fuelled fear and discrimination that still lives on to this day.

“People sort of carried this blame,” Jonathan said. “They were blamed for their own illness. You’ve decided to explore this thing. You’ve decided to go out and have sex. You’ve done this to yourself. And the chief constable of Manchester, James Anderton, talked about gay men who were ‘swirling in a human cesspit of their own making’.

“And what is really interesting is the way that suddenly there’s been this huge focus on trans people. And the way that people talk about and dismiss the trans community is exactly the same language that was being used to attack gay men in the 60s and 70s. It’s almost word for word.”

It wasn’t until 10 years ago that Jonathan finally started to feel a sense of freedom, at 65. He said: “What was amazing was the turning point for me was 2015, because in 2015 they announced that on effective medication, you cannot pass the virus.” It was a powerful sentence to hear after years of questioning his own health and that of others.

“And with it came the phrase, U = U. Undetectable equals untransmittable. And psychologically it was incredible.”

Back in the 1980s, however, Jonathan famously refused to take part in the drug trials for HIV. He said: “I was asked if I would be a part of a trial called the Convoy Trial. And they were basically trialling the very first drug that was used around HIV, which was called AZT. What nobody ever told us was that AZT was a failed chemotherapy drug.

“And so it would leave you open to opportunistic infections. That is exactly how the HIV virus works. I think one of the reasons that I’m here today is that I never touched AZT because all the people who touched AZT, if they didn’t withdraw from that trial because they were so nauseous, basically died.”

Thinking back to how far we’d come since the early days of this initially unknown virus, Jonathan recalled a time where two communities were forced to join together. He said: “What was really fascinating was that in the late 80s, there was suddenly this influx of Black African women who came to drop-in centres.

“And it was really extraordinary because they were having to deal with the fact that they were mainly surrounded by white gay men. And mainly they came from Christian communities, where homosexuality was just forbidden. So suddenly they’re having to deal with the fact that they’ve got this disease which basically ‘homosexuals have’. And that, to me, is what stigma is all about.”

Now he believes the way forward is through “raising awareness and sharing information”. He said: “I think the difficulty is that there are still parts of the population that still believe that it can’t affect them. And what is amazing now is that we have this arsenal of medication.”

The Terrence Higgins Trust works to support those with HIV, providing helpful resources and information for those interested in learning more about the virus or who are living with it themselves. The charity’s mission is to end any new cases of HIV by 2030 and with the help of people like Jonathan Blake sharing their incredible stories, there’s hope that this could be a reality.

Living with HIV has opened up so many doors for Jonathan in a world that once felt so isolating to him. Alongside his part in Pride, he has been able to share insight for other documentary films, theatre performances, and written works, as well as attending talks. With endless amounts of stories to share, he is always keen to embrace, educate and connect with people through the virus that he was once told would be the end of it all.

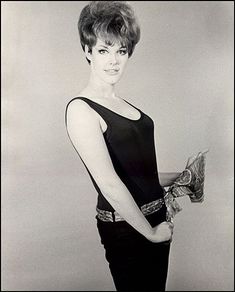

Aleshia Brevard

Aleshia Brevard was a pioneer transgender woman and has been described as ‘one of the early medical transitions’ in America. She transitioned not only before there was a trans community in San Francisco, but before the word ‘transgender’ had even been coined.

Aleshia underwent gender-affirming surgery in Los Angeles in 1962, which was one of the first such operations in the USA.

Brevard eventually wrote two biographies, the first one entitled ‘The Woman I was not born to be: A Transsexual Journey’.

Aleshia was born in 1937 and was brought up on a tobacco and cattle farm in Central Tennessee. Most of her early summers were spent hauling hay.

Aleshia was conscious of her desire to live as a woman and identified from an early age as a girl. However, she kept this inner gender identity to herself. Nevertheless, friends around her were able to sense this identity. She was described as “effeminate and artistic”. In fact, she was often mistaken for a girl, which made her teenage years awkward.

At the age of 15, having spent her youth dreaming of glamorous film stars and having left school, she took the Greyhound bus to California. Aleshia had been inspired by the iconic Christine Jorgensen, a pioneer transgender woman who made history after her gender-affirming surgery, becoming Christine and returning to the USA.

Aleshia began her transition in the late 1950s. She was one of the first transgender women working as a ‘female impersonator’ to take female hormones to aid her transitioning. She said, “Within a year of that life changing surgery I was balancing a showgirl’s headdress at the Dunes Hotel”. However, Aleshia’s dream was to be more than just a showgirl, but a Hollywood Star.

Aleshia was a multi-talented woman and worked throughout her career in many different roles: from model, entertainer/performer, showgirl, playboy bunny girl, director, professor of theatre and eventually with the publication of her memoirs, an author. She started her career as a female impersonator, as a Marilyn Monroe persona, at Finocchio’s in San Francisco in the early 1960s. From this point in her life, Aleshia travelled between Appalachia, the Eastern US and California. Having studied art at Tennessee State University, eventually attended Middle Tennessee State University, graduating with a degree in theatre.

Later, Aleshia reflecting on her transition, stated: “I did not go through gender reassignment to be labelled as transexual. I look at that as an awkward phase that I went through, sort of like a really, painful adolescence.”

After her life changing procedure, she sought the help of her family in Hartsville to recover from her surgery. Fortunately, her family were loving and supportive of her transition. However, when an opportunity to go to California with a friend came her way, she took it.

Aleshia’s regular performance as a Monroe impersonator won such renown that Marilyn Monroe herself went to the San Francisco nightclub, which was famous for it’s drag female impersonators, to see Brevard’s performance. As the act came to an end and the lights went up, Aleshia realised that Monroe was in the audience, having been discovered Monroe blew her a kiss. Monroe later recounted in her diary that seeing Aleshia’s act was like seeing herself in a film.

When Aleshia returned to Middle Tennessee State University, after retiring as a performer, she studied and earned a master’s degree in Theatre Arts. She was then able to work as a drama teacher. Aleshia also married for the first time whilst in Tennessee, eventually she married four times. In the late 1990s Aleshia returned to California and settled outside of Santa Cruz with a friend, she also worked as a substitute teacher in community theatre.

Aleshia died at the age of 79 on 1 July 2017, at her home in Scotts Valley California.