| Statement on the Supreme Court Ruling on the legal definition of sex – 30 June 2025 |

| We are deeply concerned about the harmful implications of the recent Supreme Court ruling on the legal definition of ‘sex’ in the Equality Act 2010, for the trans, non-binary and intersex communities of Manchester and beyond, as well as for other groups. We stand in solidarity with trans, non-binary and intersex people. The negative repercussions of this ruling are already starting to be felt, with the safety of trans, non-binary and intersex people at risk. There are also potential negative implications of the ruling for other marginalised groups, such as the wider LGB communities, gender non-conforming people, and cisgender women. It is more important than ever for allies to actively challenge discriminatory language and actions and express solidarity with the trans+ communities. |

Pride month may be over, but the fight for LGBT+ safety and dignity continues.

At Out In The City we’re proud all year round.

Hungary Pride ban prompts largest ever parade in Budapest

The right-wing Fidesz party, which has seen Viktor Orbán as the European country’s Prime Minister since 2010, passed an anti-LGBT+ law banning Pride marches in Hungary on the grounds that the depiction of homosexuality was a threat to minors.

The ban (in March this year), which was met by protests from opposition politicians and members of the public alike, proposed fines of up to 200,000 forints (£420) for organisers of Budapest Pride, and anyone attending, claiming the event could be considered harmful to children.

In further response to the Hungary Pride ban, tens of thousands took to the streets of Budapest on 28 June to defy Orbán, including the city’s Mayor, Gergely Karácsony.

The event ended up being the country’s largest-ever parade by some way, far outnumbering the expected turnout of 35,000 to 40,000 people.

“We believe there are 180,000 to 200,000 people attending,” the president of Pride, Viktória Radványi, said. “It is hard to estimate because there have never been so many people at Budapest Pride.”

5,000 dancing activists make the “world’s largest” human Pride flag

Five thousand Mexican LGBT+ activists in Mexico City reportedly set a world record by making the largest-ever human Pride Flag in the city’s central main square, known as Zócalo (Constitution Plaza).

The display began at 10.30am on 22 June and lasted for two hours. Each participant wore a t-shirt displaying one of the traditional Pride flag’s six colours, carried an umbrella of the corresponding colour, and moved to the song “A quién le importa” (“Who cares”) by Alaska and Dinaramaas – a defiant song about staying true to oneself in the face of societal disapproval.

A drone captured photos and videos as the participants filled the plaza’s entire 787 square foot space.

Mexico City Mayor Clara Brugada joined the crowd and said of the event: “Mexico City is and will continue to be the city of rights and freedoms. This monumental image we draw with our bodies and colours will be a powerful message to the country and the world. Mexico City is the capital of pride, diversity, peace and transformation.”

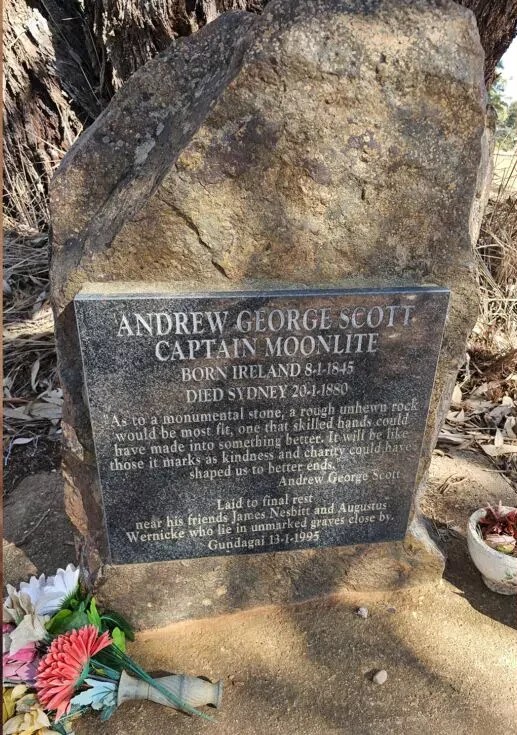

How the graves of a legendary Australian outlaw and his soulmate became a heritage site

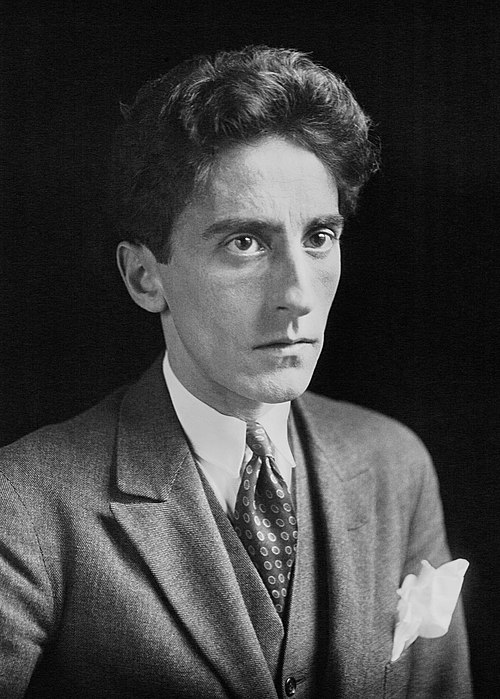

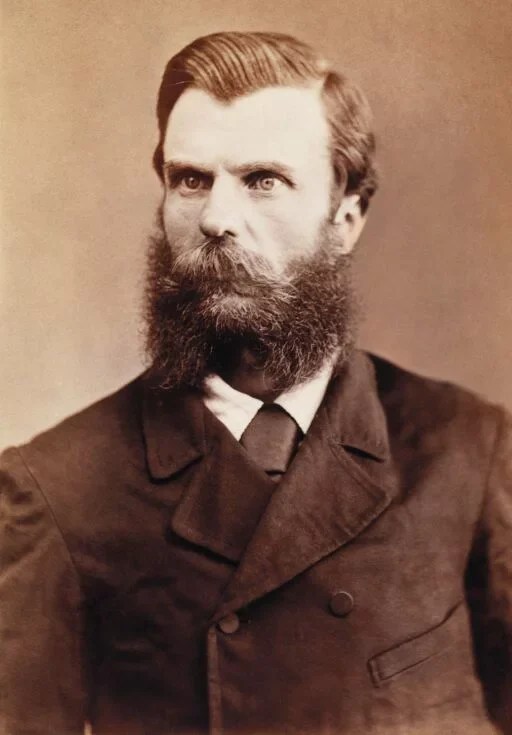

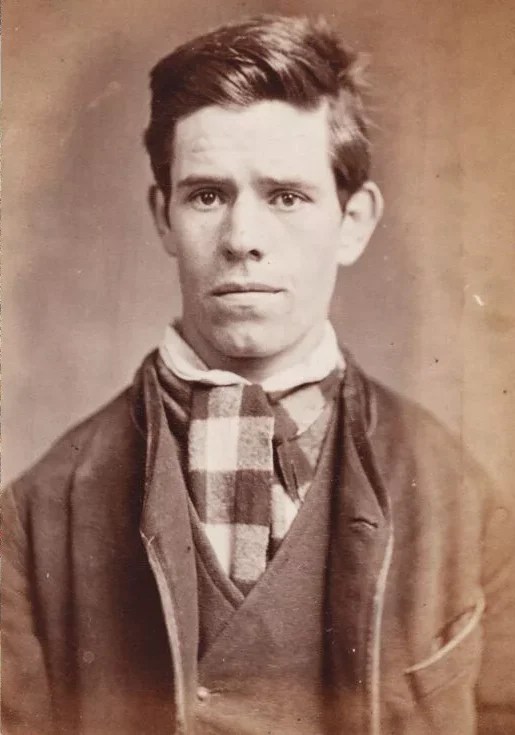

Andrew George Scott aka Captain Moonlite (5 July 1842 – 20 January 1880) (left) and James Nesbitt (27 August 1858 – 17 November 1879) (right).

It was late 1879 in the Australian outback, and Captain Moonlite and his gang of young bushrangers were desperate and on the brink of starvation. Depending on who you believe, they’d come to Wantabadgery Station – roughly halfway between Sydney and Melbourne – either on the unkept promise of work, or with the full intention of robbing the locals.

Whatever their motives, Moonlite and his hungry men stormed the little settlement and its surrounding businesses, stealing supplies and booze and taking 25 prisoners. A shootout with law enforcement ensued, during which a police constable was mortally wounded – as was Moonlite’s beloved gang member, James Nesbitt. Local newspaper reports at the time said that Moonlite wept over Nesbitt “like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately.”

Later letters from Moonlite revealed that he and Nesbitt shared a deep connection that was clearly more than just an intense bromance. “My dying wish is to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship,” he wrote. “We were one in hopes, in heart and soul, and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.”

Bushrangers were to Australians what Wild West outlaws were to Americans, a motley assortment of frontier bandits. In terms of contemporary infamy in 1879, Captain Moonlite was not yet a top-tier bushranger on par with the notorious Ned Kelly, but he was well on his way.

Andrew George Scott was born in Ireland in 1842, and he came to Australia in 1868 by way of New Zealand. Ostensibly a lay preacher studying for the Anglican priesthood, Scott conducted his first bank heist the following year in the gold mining town of Mount Egerton, leaving a note behind meant to throw authorities off the track, signed with the intentionally misspelled moniker Captain Moonlite.

While in prison for his crimes at Melbourne’s Pentridge Gaol in the 1870s, Scott met fellow prisoner James Nesbitt, 16 years his junior, and the two became tightly bonded. When Scott was released from Pentridge in March 1879, young Nesbitt (who had been released a year earlier) was waiting for him at the gate, and the two moved into a boarding house together in the now-bohemian Melbourne neighbourhood of Fitzroy.

In the months that followed, Scott simultaneously embarked on a speaking tour urging prison reform in Australia’s harsh penitentiaries while becoming the subject of tabloid accusations about his potential connections to unsolved local crimes. During his speaking tour, he bonded with several young men, four of whom, along with Nesbitt, became part of his fledgling bushranger gang.

After the Wantabadgery shootout in November 1879, Scott was arrested and taken to Sydney’s Darlinghurst Gaol, where he and fellow surviving gang member Thomas Rogan were both hanged for the murder of Constable Bowen on 20 January 1880. Scott went to the gallows wearing a lock of his beloved Nesbitt’s hair on his finger.

Scott’s dying wish to be buried next to his “dearest Jim” – who had been unceremoniously entombed near their last shootout in the outback town of Gundagai – was of course denied by authorities, and he was instead interred in an unmarked grave at Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery.

Flash forward 115 years to 1995, when two local Gundagai women, moved by Scott’s century-old burial wishes, led a successful grass-roots campaign to have his body exhumed from Rookwood and transported the 220 miles to North Gundagai Cemetery, where Nesbitt is believed to also lie in an unmarked grave. Scott’s new tomb was given a proper stone marker.

New South Wales added Scott and Nesbitt’s graves to its State Heritage Register in March 2025. Minister for Heritage, Penny Sharpe said that the listing “reflects the desire to tell the diverse stories that reflect the rich history of NSW” and have “always existed” in the state.

Birthdays