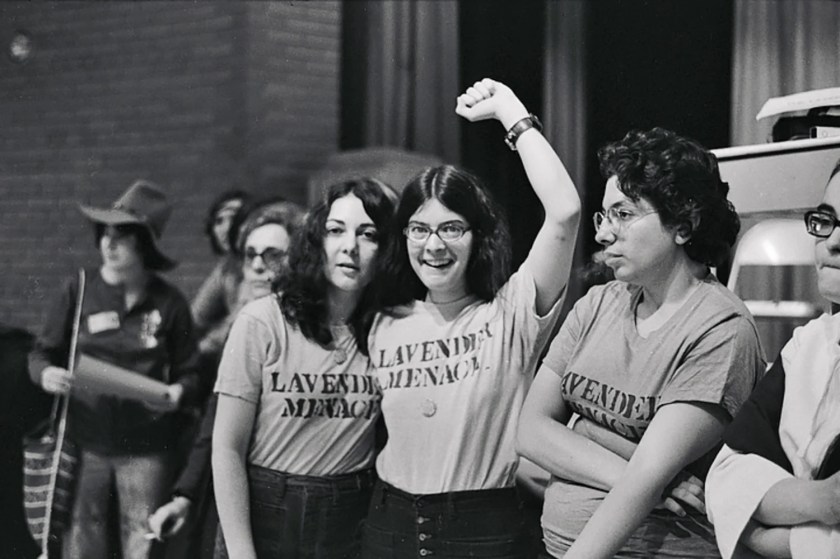

International Lesbian Visibility Day

Lesbian Visibility Day is celebrated annually on 26 April and falls within Lesbian Visibility Week. This awareness week runs from 21 to 27 April 2025.

International Lesbian Visibility Day is a day to recognise and celebrate the contributions of lesbian women around the world. The day was created in 2008 to raise awareness of the issues faced by lesbians, and to encourage them to live authentically. International Lesbian Visibility Day is celebrated annually and is supported by various organisations and individuals around the world.

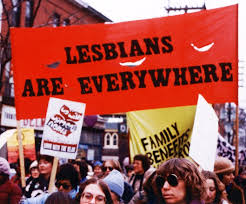

To celebrate International Lesbian Visibility Day, events and activities are held in cities and towns around the world, including marches, rallies, and other public events. Organisations such as the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) also hold events to raise awareness and celebrate the day. Additionally, many individuals take part in online initiatives such as social media campaigns, online forums, and blogs.

International Lesbian Visibility Day is a day to recognise and celebrate the achievements, contributions, and unique experiences of lesbian women. It is also a day to reflect on the challenges faced by these women, and to promote a greater understanding of the LGBT+ community. By celebrating International Lesbian Visibility Day, we can create a culture of acceptance and inclusion, and help to create a more equal and just society for all.

How did International Lesbian Visibility Day first start off?

International Lesbian Visibility Day was first celebrated in 2008 to bring attention to the issues that lesbian women face around the world. The day was started in order to bring visibility to the struggles and successes of these women in the fight for equality. International Lesbian Visibility Day also serves to create a safe space for lesbians and bisexual women to celebrate and express themselves. The day was created after a group of activists and allies, working with the ILGA and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Youth and Student Organisation (IGLYO) realised the need for a day to celebrate and bring visibility to the issues of lesbians and bisexual women. The day was created to celebrate the diversity of the lesbian, bisexual and queer community and to emphasise the importance of visibility for these women.

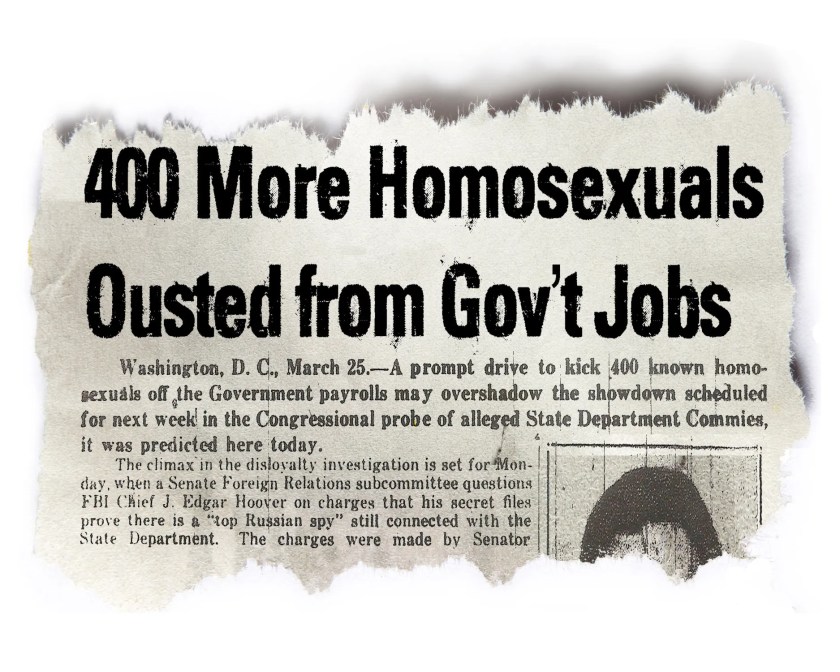

Lesbians and the Lavender Scare

Lesbian relationships among government workers in the United States were seen as a threat to national security in the 1950s. But what constituted a lesbian relationship was an open question.

When the US government targeted LGBTQ employees in the Lavender Scare of the 1950s, the most numerous victims were gay men. Lesbians were also driven out of federal jobs. But that was tricky because officials had trouble figuring out what a female homosexual might be.

One rationale behind getting gay people out of government employment was that they could be subject to blackmail. But a deeper one was the idea that being gay reflected a failure of “character.”

While experts of all sorts believed there was something unsavoury about homosexuality, they conceptualised what this meant in a variety of ways. Some used the paradigm of “sexual inversion,” which identified same-sex attraction with gender nonconforming physical appearance and behaviour. Others insisted that homosexuality was a matter of acts, not identity – as late as 1965, when Civil Service Commission John Macy Jr met with members of the early gay-rights organisation the Mattachine Society, he explained that “we do not subscribe to the view, which is indeed the rock upon which the Mattachine Society is founded that ‘homosexual’ is a proper metonym for an individual.”

Still, gay identities were widely understood to be a thing, for men and women. In their 1951 book Washington Confidential political reporters Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer claimed that “there are at least twice as many Sapphic lovers as fairies” in government employ.

And soon, those women were coming under fire. In 1954, the US Senate Committee on the Judiciary was faced with allegations that one subcommittee’s staff was largely made up of lesbians whose interpersonal drama was hurting office morale.

That same year, similar allegations swept through the Federal Housing Administration. Some accused women immediately resigned, but others fought back. Two nurses, Grace O’Lone and Mary Meyer, acknowledged that they had previously been in a sexual relationship but claimed they no longer were. At the same time, Meyer expressed her disapproval of the entire inquiry, arguing that officials should focus on fighting Communism, “a much more dangerous thing than even the most outstanding sex pervert.”

But which acts between women might constitute perversion was an open question. While two men kissing or holding hands clearly broke taboos, with women it might reflect acceptable friendly affection. On the other hand, one Navy psychiatrist told a Senate committee that sexual activity in lesbian relationships might be limited to “hugging and kissing” and that “it is possible for two women to be in something of a homosexual relationship without either of them being fully aware of it.” In the case of Meyer and O’Lone, defence attorney Al Philip Kane argued that true lesbianism was only possible if one of the women had an enlarged clitoris capable of vaginal penetration.

After sitting through long discussions of what they did or didn’t do in bed, Meyer and O’Lone beat the allegations – though only by convincing the officials that they had successfully overcome their sexual desires and now lived together chastely.

Men often put off doctor’s visits again and again … until there comes a tipping point

Men go to the GP less than women and are less likely to be registered at a dental practice or use a pharmacy

Men often put off seeking medical treatment – until their symptoms became unbearable or until a loved one pushes them to get help.

It’s well known that men go to the doctors less than women, and data backs this up.

According to the Office for National Statistics Health Insight Survey, commissioned by NHS England, 45.8% of women compared to just 33.5% of men had attempted to make contact with their GP practice for themselves or someone else in their household in the last 28 days.

Men were more likely to say they weren’t registered at a dental practice and “rarely or never” used a pharmacy, too.

They also make up considerably fewer hospital outpatient appointments than women, even when pregnancy-related appointments are discounted.

Men are “less likely to attend routine appointments and more likely to delay help-seeking until symptoms interfere with daily function,” says Paul Galdas, professor of men’s health at the University of York.

This all affects men’s health outcomes.

Experts say there’s a long list of reasons why men might put off seeking medical help, and new survey data from the NHS suggests that concerns about how they are perceived come into play.

In the survey, 48% of male respondents agreed they felt a degree of pressure to “tough it out” when it came to potential health issues, while a third agreed they felt talking about potential health concerns might make others see them as weak. The poll heard from almost 1,000 men in England in November and December 2024.

Society associates masculinity with traits like self-reliance, independence and not showing vulnerability, says social psychologist Prof Brendan Gough of Leeds Beckett University. “Men are traditionally supposed to sort things out themselves”.

“It’s worrying to see just how many men still feel unable to talk about their health concerns,” says Dr Claire Fuller, NHS medical director for primary care. She notes that men can be reluctant to seek medical support for mental health and for changes in their bodies that could be signs of cancer. GPs are often the best way to access the help they need,” she adds.

‘Men are inherent problem-solvers’

The data suggests that when people were unable to contact their GP practice, men were significantly more likely than women to report “self-managing” their condition, while women were more likely than men to go to a pharmacy or call 111.

“Many men feel that help-seeking threatens their sense of independence or competence,” Prof Galdas says.

Prof Galdas points to other factors deterring men from going to the doctors, like appointment systems that don’t fit around their working patterns.

Services also rely on talking openly about problems, he suggests, which doesn’t reflect how men speak about health concerns – and there are no fixed check-ups targeting younger men.

Women, in contrast, are forced to engage in the health system because they might seek appointments related to menstruation, contraception, cervical screenings or pregnancy.

They are largely in control of organising their family’s healthcare too. For example, roughly 90% of the people who contacted the children’s sleep charity Sleep Action for help in the last six months were mums, grandmothers and other women in the children’s lives.

Because women are more integrated in the healthcare system – through seeking support for both themselves and their children – they are more health-literate and are often the driving force behind their partners seeking medical help, according to Prof Galdas.

Men have a different attitude towards healthcare. Many see it solely as treatment – solving their problems – rather than preventative. Men are, for example, less likely, to take part in the NHS’s bowel cancer screening programme. As Prof Galdas says: “men often seek help when symptoms disrupt their ability to function.”

Connection can make a big difference

In recent years, support groups for men with cancer and mental health conditions have sprung up.

Experts say that while men’s attitudes towards healthcare are gradually changing for the better, more work still needs to be done.

Prof Galdas believes men will engage more if services are redesigned to meet their needs – proactively offering support, having flexible access and focusing on practical action to improve mental health issues.

“There’s good evidence from gender-responsive programmes in mental health, cancer care, and health checks showing this consistently,” he says.

Adding general health checks for men in their 20s to get them more used to accessing medical care, would be another improvement.

They’re already available through the NHS for people aged 40 to 74, but introducing them for younger men who might not otherwise go to the doctors would embed the idea that you can come and use health services.

Did I Say?