North West Computer Museum

Architects Bradshaw, Gass & Hope based in Bolton were the masterminds behind some of the most incredible buildings in the north west during the Industrial Revolution. These included Manchester’s Stock Exchange (1904-06) and the Royal Exchange (1914-21) alongside Leigh Spinners Mill, an iconic Grade II* listed building residing within a large eight acre site.

We visited Mill 2, which was built in 1925. It’s an iconic landmark in Leigh and now 100 years later is a community hub, housing a number of tenants including the North West Computer Museum on the 4th floor. Luckily, the lift was working!

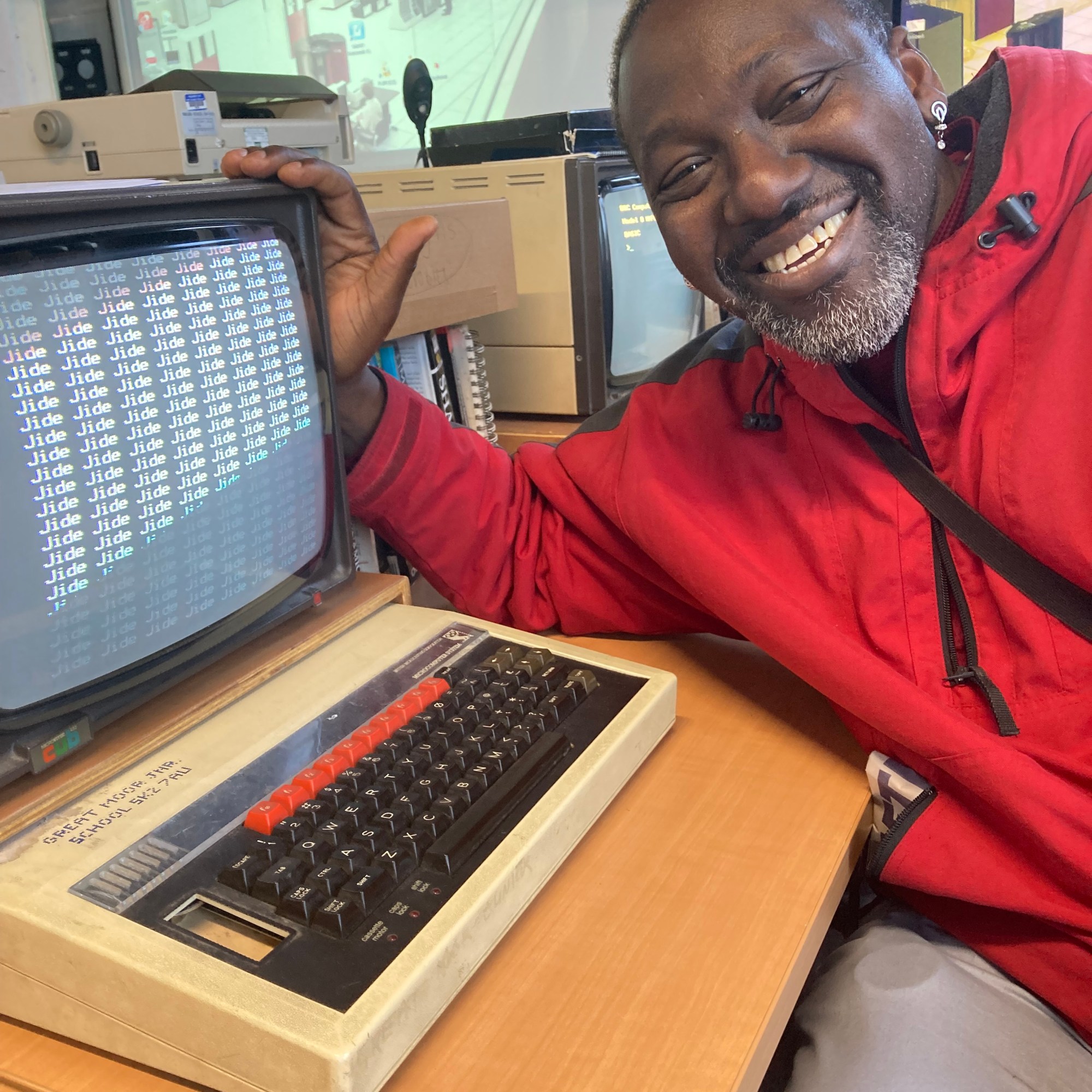

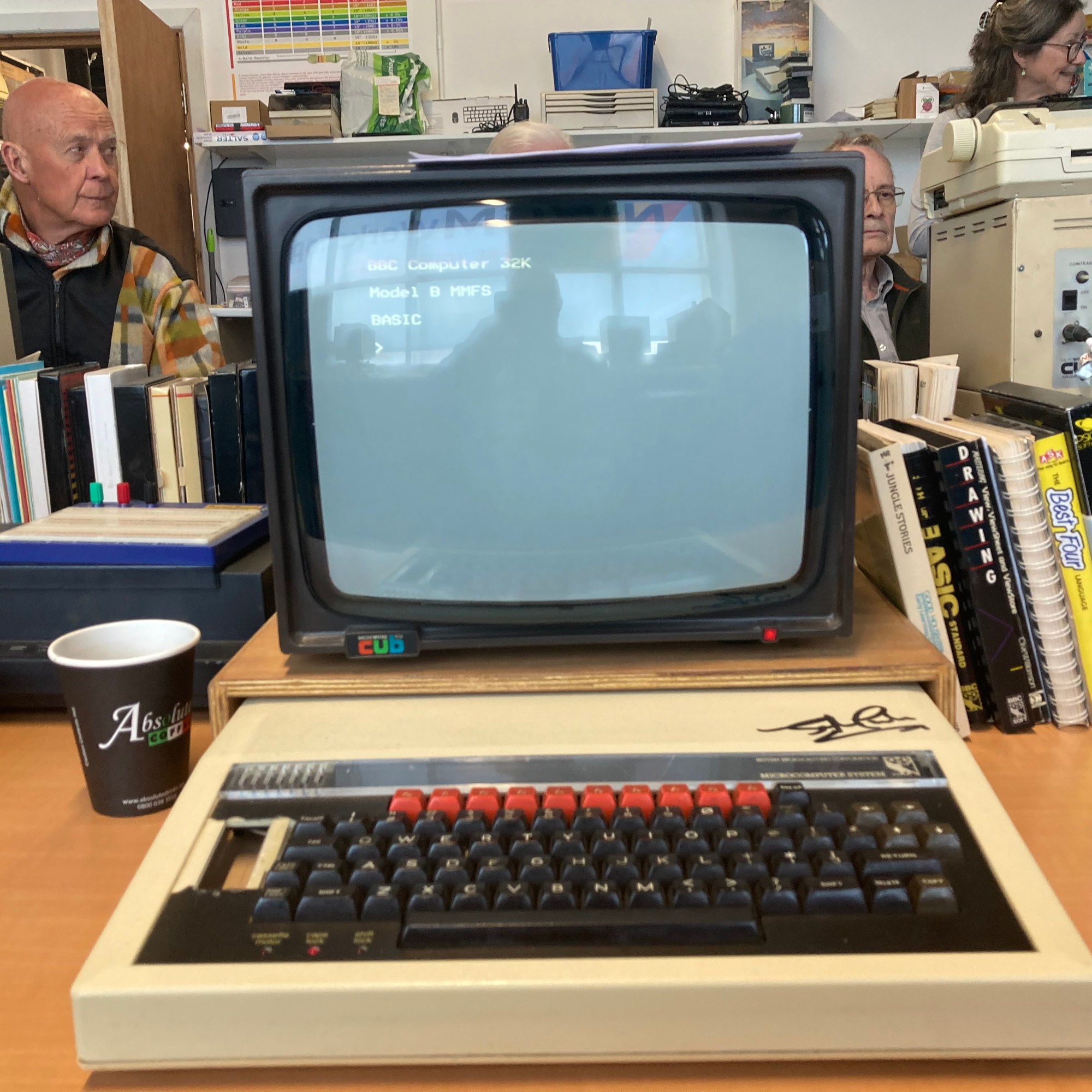

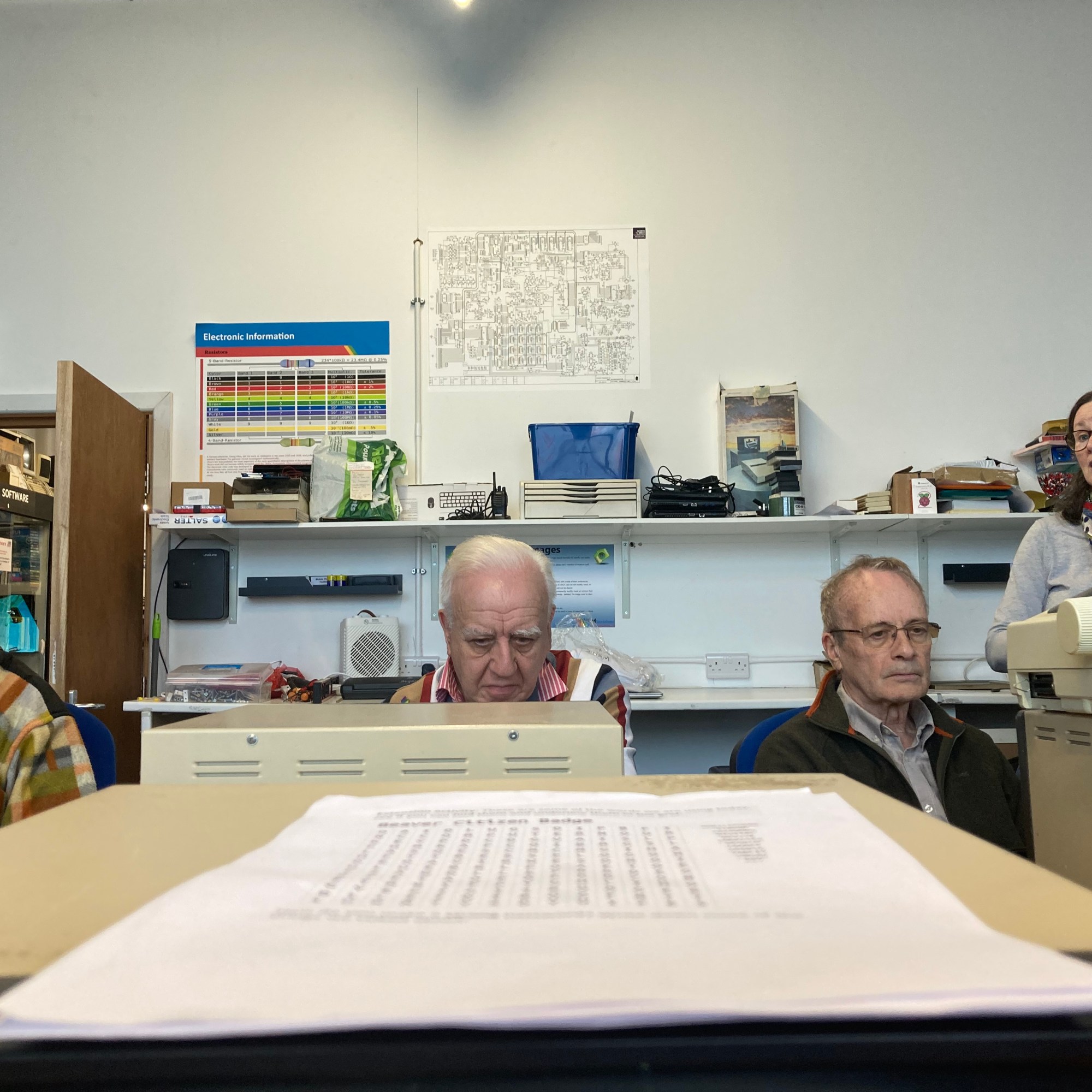

Whilst there we had a coding taster session on BBC Micro 32K computers which dated back to the 1980s. Liz, our tutor, gave some examples of coding. It’s amazing how computers have changed in such a relatively short period of time.

There was so much to see with hands on exhibits, dating from the 1970s to the present day, including retro arcade games and an internet café.

Tony was tasked with writing down everyone’s lunch orders in the café and was rewarded with a free cup of coffee!

More photos can be seen here.

State of Ageing Report 2025

This year’s State of Ageing report paints a picture of the older population in England, using a variety of national data sources.

The Centre for Ageing Better’s new analysis shows that quite simply, where you are born in England determines how long you live and how well you age.

Living in the poorest parts of England can cost you almost five years of your life. Men living in the poorest areas of the country can expect to live 4.4 fewer years on average than those living in the wealthiest areas of England.

All of us deserve the best possible lives as we grow older, and our whole society reaps the rewards when people can age well. The Centre for Ageing Better’s new analysis of the state of ageing in England in 2025 reveals millions more of us are living into our seventies, eighties, nineties and beyond, in good health, working for longer and supporting our communities through volunteering and caring.

But this report also highlights that this rosy, positive picture of ageing is unobtainable for many, such as those who are living in poor housing, in poverty and poor health, and who are isolated from their communities and society. The report shows the impact of regional inequalities that determine the quality of people’s later life. Quite simply, where you are born in England determines how you live and how well you age.

This summary report and the accompanying chapters draw attention to the disparities in resources, opportunities and outcomes that exist between different geographic areas – whether regions or local authorities. Inequalities between places in things such as access to decent and affordable housing, access to jobs (and good jobs), and the extent to which these places provide and maintain infrastructure such as transport and public services, give rise to inequalities in outcomes for people, including life expectancy and health.

We need the government and others to take inequalities in ageing seriously and address the lack of political focus that has meant chronic underinvestment in helping people to age well. We also need to address the pervasive ageism in society that produces negative and distorted views of ageing and older people. By doing this, we can properly value and benefit from the contributions of older people to our society.

Download the report here.

Lawrie Roberts, Pride in Ageing Manager at the LGBT Foundation, will be speaking today (27 March 2025) about LGBTQ+ communities at the Age Friendly Futures Summit on a panel titled “Understanding differing experiences of ageing”.

Queer Treasures at the Manchester Central Library – 5

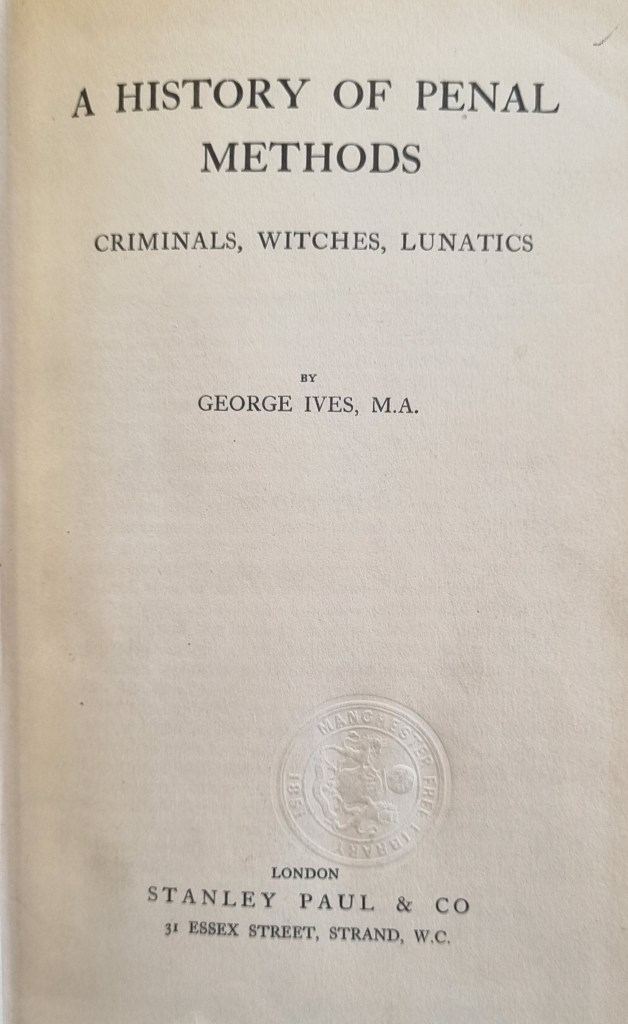

‘A History of Penal Methods: Criminals, Witches, Lunatics’ by George Ives

This is the fifth in a series of articles about queer treasures that are currently found in the Archives held at Manchester Central Library.

George Cecil Ives (1867-1950) was an English writer of Uranian poetry and an early campaigner for homosexual law reform. Whilst at University at Magdalene College in Cambridge, he became interested in penal reform, and being gay himself, was particularly concerned with the way that the state dealt with those minorities whose lives involved transvestism and homosexuality. He was also a successful cricketer, briefly playing for the Marylebone Cricket Club.

In 1892 he met Oscar Wilde and endeavoured to recruit him to ‘the Cause’, which Ives defined as the ending of the legal and social oppression of homosexual love. The following year he also met Lord Alfred Douglas, with whom he had a brief affair.

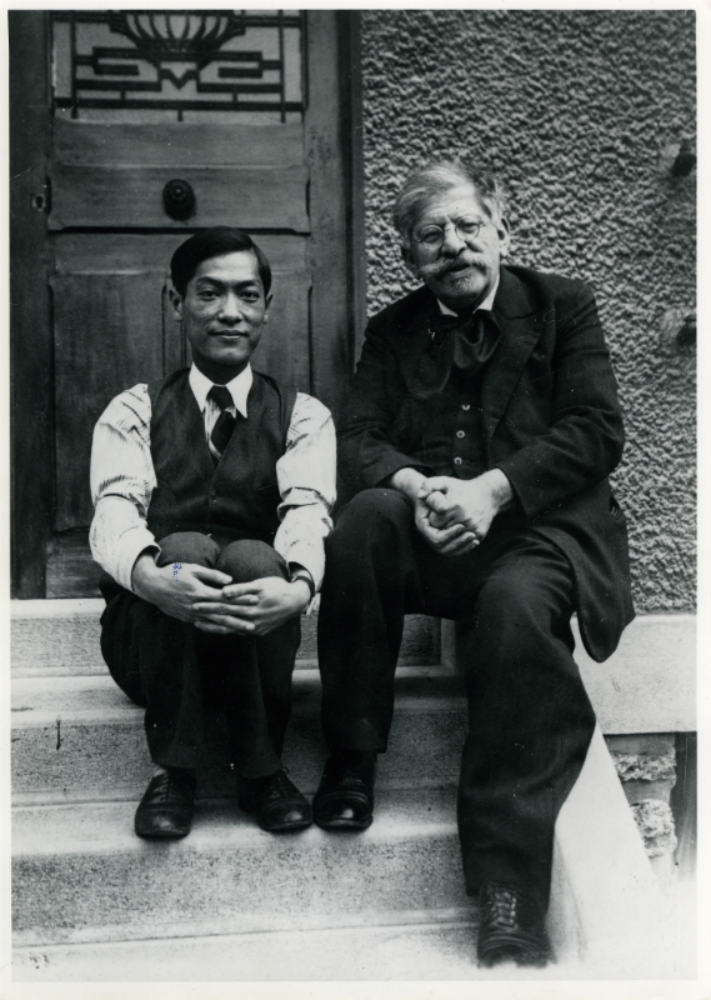

By 1897, Ives had founded the Order of Chaeronea, a secret organisation for homosexuals, whose members occasionally gathered together and talked about their own lives and about how positive legal and social changes for homosexuals could be effected. Ives was also a friend of Edward Carpenter and, in 1913, he, together with Carpenter, Magnus Hirschfeld, Laurence Houseman and others, founded the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology, which aimed to bring about progressive social change by promoting and supporting the scientific study of sex. Ives visited prisons across Europe, took part in international conferences on penal reform and wrote books and articles to promote his ideas.

Out of this study of, and engagement with, prison reform, came his 1914 work, on ‘A History of Penal Methods’. After looking at a variety of criminal behaviours and, in particular, the treatment meted out historically towards those who do not conform to rigid social norms, such as witches and the mentally ill, he turned his attention to homosexuals, pleading for a radical legal transformation in society’s approach to the whole issue. In his writings his employment of language can be seen to reflect the vocabulary of his age, by his use of the terms ‘sexual inverts’ and ‘homogenic attraction’ to refer to LGBT men and women.

Ives chided the fact that there was limited general understanding about sexuality, as the subject was often deemed unsuitable for public discussion. He argued however, that ‘if the legislator makes one theory of the psychology of sex the basis for passing a law which sends citizens to penal servitude, it is impossible to shut out such a theory from public discussion’ (p291). He was determined to argue the case for the reform of laws that constrained LGBT people, which he did for the rest of his life.

Ives posited same-sex attraction as ‘an innate instinct’ (p294) and that –

The sexual inverts may be compared to the left-handed. They are indeed always a minority in every population, but an eternal minority which neither laws nor even religious systems have ever altogether swept away … the names of some of them are written for all time in the world’s history. (p292)

He maintained that sexual inversion was ‘A deep inevitable impulse’ which ‘could never … be penalised out of existence’ (p295) but that legislators had refused to listen and so, ‘hopelessly, the unfortunate inverts have been left to policemen.’

In his book, Ives reviews the theories of progressive contemporary British and Continental sexologists to suggest a ‘latent bisexuality in each sex’ (p299) but that ‘Custom, education, costume and maternity have all tended to accentuate the difference and obliterate the likeness of the two sexes …’ (p299). Human variety had not however been totally eradicated and ‘thus among the infinite kinds of combination we also find the homogenic union’ (p300).

Ives points towards continental criminal codes (France, Italy etc) where ‘an age of consent is allowed for homosexuality to both sexes above which the law refrains from interference’ (p361) and urges that this be applied to other penal codes. Sadly English ‘inverts’ had to wait almost 100 years later, until 2001, for an equal age of consent to become a reality.

Generally less well-known than Edward Carpenter or Magnus Hirschfeld, Ives was nevertheless at the forefront of campaigning for the equal treatment of queer people before the law in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He, and other reformers who worked energetically for what were, then, unpopular causes, laid much of the groundwork for the rights we enjoy today.

Arthur Martland © 2025