Trouble at Mill

This week 25 of us headed oop north to that Burnley in darkest Lancashire to visit Queen Street Mill Textile Museum. We took buzz X43 and had us dinners in a Wetherspoons “The Boot Inn” afoor teking another buzz up to Harle Syke. I was reet chuffed that we found da place without too much fretting or mithering.

We had a guide – Roger – who were a reet good egg. He knowed everything bout the place. He weren’t a thickun at all. The machinery were dead loud an’ each person worked four looms by their sen. Mind you, if you worked there you wouldn’t nod off, or you’d end up with cloth ears.

Who’da thowt it? Before we left we had us a brew.

More photos can be seen here.

Exploring the Not-So-Secret Gay Life of Famed Playwright & Performer Noël Coward

Noël Coward was an acclaimed actor, playwright, songwriter, singer and director.

Born to a working class family in the suburbs of London in 1899, he turned his passion for the arts into a multi-faceted career that established him as one of the most revered voices in entertainment, from the West End to Broadway, thanks especially to his hit plays like Private Lives and Blithe Spirit (by 30, he was already the highest paid writer in the world!).

He was also gay – a truth that almost everyone knew, but no one talked about.

Of course, that’s not the most surprising thing considering the era Coward rose to prominence. But it’s only in recent years that we’ve begun to fully appreciate the impact he made, not just as a dramatist, but as a queer dramatist.

While his work was never expressly gay, it was undoubtedly imbued with his queer sensibilities. Take for example, “Mad About The Boy,” one of his most well-known numbers written for the comedy I’ll Leave It To You, originally intended to be sung by women daydreaming about their movie-star crush.

But, come on: “I know it’s stupid to be mad about the boy, I’m so ashamed of it but must admit, the sleepless nights I’ve had about the boy”? It’s not hard to read those lyrics from the perspective of a gay man!

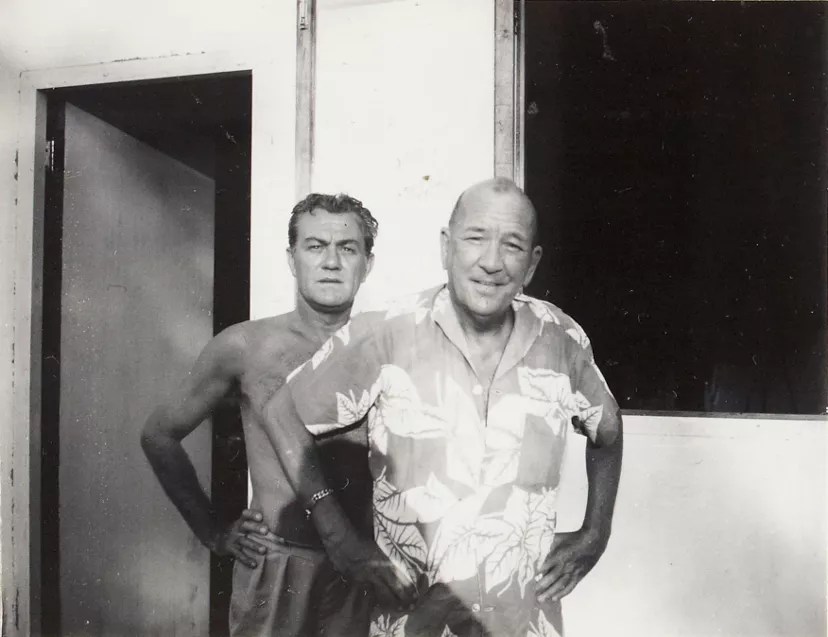

While Coward largely kept his private life private, he did eventually find a hunky screen idol of his own: The South Africa-born stage and screen actor Graham Payn, who would appear in a number of the writer’s works over the years. The true nature of their decades-long romance was kept a secret until after Coward passed.

From his lovers to his lavish lifestyle to his lasting legacy, all of that and more is explored in the fascinating documentary Mad About The Boy: The Noël Coward Story – taking its name from his signature song, naturally! – directed by filmmaker Barnaby Thompson (who also helped produce Spice World).

The film recounts his life, from impoverished childhood to jet-setting star up until his passing in 1973, told largely through his own words, music, and rarely seen home movies.

Listen carefully and you’ll hear a number of familiar voices. For one, many of Coward’s famous contemporaries and admirers – from Frank Sinatra to Lauren Bacall to Dame Maggie Smith – sing his praises via archival footage. And, reading direct from the icon’s diaries, as the voice of Noël Coward himself, is out star Rupert Everett.

And the whole thing is narrated by recent Emmy winner Alan Cumming, whose lilting Scottish brogue is the perfect complement to Coward’s incredible story.

Watch the trailer for Mad About The Boy: The Noël Coward Story below:

LGBTQ+ Abuse in Immigration Detention

As soon as Joel Mordi was driven into the asylum detention compound, he described it as if the ‘gates of hell’ had just opened.

Wearing a blazer and Doc Martens with rainbow laces, he was guided through the big hall of Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) lined with yellow doors and gangs of people clustered together.

Joel immediately felt powerless, as homophobic insults from fellow detainees started.

“People called me a sissy. Then there was faggot and batty boy, but there were so many street terms that I didn’t know. The ones I couldn’t understand were probably really bad. It felt like I had a target on my back, but the officer I was with didn’t do anything.”

Joel was just 21 on 5 November 2019, when he touched down in London after leaving his home country of Nigeria – where homosexual acts are punishable by up to 14 years in prison. He fled Lagos after organising a public protest for LGBTQ+ rights and receiving death threats as a result.

But his ordeal wasn’t over. Claiming asylum at Heathrow Airport immediately after landing, he says he was held in a waiting room for 11 hours – where he was strip searched – and then transferred to Harmondsworth IRC.

Joel spent one night in the facility’s annex, then was transferred to the main detention area, where the homophobic insults from fellow detainees occurred. Unfortunately, that was just the beginning.

Joel adds: “One night, the door handle started rattling and someone I didn’t know opened it. He had come to gain sexual favours and threatened to hurt me if I didn’t comply. Eventually, I did what he wanted and then he left.

The following night, he came into my room again. This time, he wanted something different, but I couldn’t go through with it. He tried but I screamed and he left,” he says.

Joel was left shaken and scared for his life, especially with how eerily silent it was in the aftermath when his world felt like it had completely crumbled.

At the time, he tried to report to one of the officers what had happened to him, but Joel says she didn’t want to hear it and so dismissed him.

Five years on, Joel still recalls vivid and traumatising details of the assault, including the man smelling of weed or the countless cuts on both of his arms. Thankfully, to Joel’s relief, he was granted bail less than a week after his detainment. But the damage was already done.

In the years since, his mental health suffered immensely, including insomnia, nightmares, flashbacks and major PTSD. “Detention never really leaves you,” he says. “I remember everything. I’ve tried to undo it but there are some things that will be forever etched in me.”

According to figures via a Freedom of Information (FOI) request from immigration charity Rainbow Migration, there were at least 259 LGBTQ+ people held in immigration detention in 2023 – which is almost exactly double the amount (129) in 2022.

The Home Office does not systematically collect or publish any data on LGBTQ+ people in detention, which is why they’re reliant on FOI data – but even that has its limits.

The data provided is missing eight months’ worth of numbers from Derwentside and nine months’ worth from Colnbrook and Harmondsworth – some of the biggest detention centres in the UK. That missing data, and the fact that what data there is relies on LGBTQ+ people voluntarily outing themselves to detention centre staff, is why the true number will be significantly higher.

Thankfully, since his detention, Joel has been supported by LGBTQ+ and immigration charities – AKT, Safe Passage, Micro Rainbow and Rainbow Migration – who he says have been a ‘lifeline’.

But after his traumatic ordeal in detention, he has a message for the Home Office. ‘If detention is already a damned place for our counterparts, times it by at least 11 and that’s how it is for LGBTQ+ people,’ Joel says. ‘It’s not fit for purpose’.

* Name has been changed.