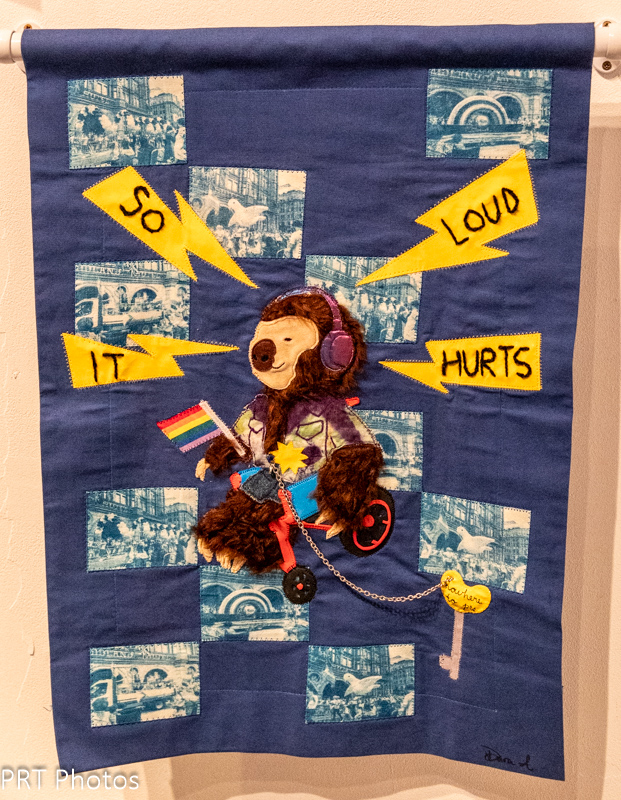

The Pride Parade Goes On Without Me

LGBT+ identity is a complicated maze to navigate particularly for those who belong to the disabled, neurodivergent and/or mentally ill communities.

LGBT+ nightlife is a huge part of the LGBT+ experience. In Manchester, our Gay Village is an important and historical LGBT+ space, but contains few accessible venues. Lack of step-free access and sensory overload are just two of the issues that disabled LGBT+ people can encounter along Canal Street, and these barriers extend to Pride events too.

Another element of LGBT+ community is our activism. Pride is a protest, and LGBT+ communities come together everywhere to advocate against unfair treatment. Yet activism often requires a physical presence, and any risk of arrest carries greater difficulties for those with intersectional identities.

The works displayed at the exhibition are all created by LGBT+ and disabled artists based in Greater Manchester, expressing their joys and frustrations around engaging with the LGBT+ community. This includes three textile pieces from lead artist Data SF Addams and Oliver Waite’s poem “The Schizophrenic Queer” from which the tile of the exhibition has been taken. The People’s History Museum hopes that platforming these voices will lead to a more in-depth understanding of accessibility and inclusion.

See more photos here.

Hadrian’s Wall

English Heritage has declared that Hadrian’s Wall is a symbol of LGBTQIA+ history.

Hadrian’s Wall spans 70 miles across Northern England – the relics of which remain 1,900 years after it was built.

The charity, which is responsible for managing over 400 historical monuments, buildings and places across England, recently listed seven locations that are “linked to England’s queer history”.

Other locations identified by the English Heritage as part LGBTQIA+ history include Chiswick House, Walmer Castle, Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Eltham Palace, Rievaulx Abbey and Ranger’s House.

On their website, English Heritage reflected on the “lasting mark” Emperor Hadrian “left on Britain” and his “intense adoration for his male lover Antinous”. They further explained: “To understand Hadrian’s Wall you have to understand the Roman emperor who built it – his career, his life and the times in which he lived.”

Whilst Hadrian may have been married to Trajan’s great-niece Sabina Augusta, he was known for his relationship with the young Bithynian male, a practice which was common for Roman men, according to their website.

A Roman man was at liberty to choose sexual partners as long as he remained the dominant one in any sexual encounter. Antinous joined the emperor and his wife on the tours of his empire, which he took control of in 117 AD. Tragically, Antinous drowned in the Nile in October 130 AD, at around 20 years old.

Hadrian was reported at the time to have “wept for him like a woman,” according to National Museums Liverpool.

In a state of adoration and despair for his young lover, Hadrian founded the city of Antinoöpolis close to the location of his tragic death to immortalise his memory. He went further to make Antinous out as a God-like status, and placed statues of his image across the empire, something that was considered highly abnormal for someone outside of the imperial family.

Images of Antinous were subsequently used in private homes as a discreet nod to homosexuality. After all, they have been referred to as “the most famous homosexual couple in Roman history.”

Declaring the wall a piece of LGBTQIA+ history caused quite a stir online with the non-LGBTQIA+ crowd – academics criticised the charity for their “totally misguided” link.

Professor Frank Ruerdi told The Daily Mail: “English Heritage appears to be in the business of reading history backwards and discovering LGBTQ culture in the most unlikely places.”

Jeremy Black, an emeritus professor of history at Exeter University, added: “The idea that Hadrian’s Wall is an exposition of what can be seen as queer history is totally misguided.” In contrast, human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell told the publication it is “important that this hidden history is revealed.”

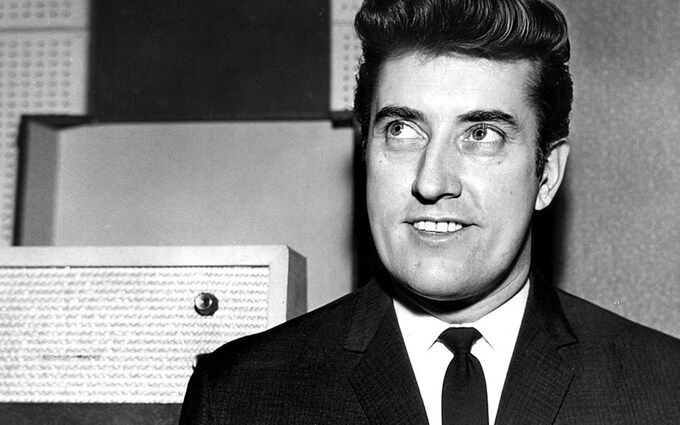

The First Gay British Rock Song Offers a Peek at Cruising in The ’60s

“Do you come here often?”

There’s no doubt well-to-do heterosexual couples in the late ’60s found themselves (and their respective supper parties) scandalised when they flipped over this old 45 from British instrumental group The Tornados.

The band, led by gay producer Joe Meek, scored a No 1 hit in the US and UK with science fiction-inspired track “Telstar” in 1962. However by 1966, the crew had long been replaced and was past their prime. Their final single was the innocuous “Is That A Ship I Hear,” though its B-side featured quite the fruity surprise.

“Do You Come Here Often?” starts with two minutes of inoffensive instrumentation, led by a jazzy organ, until a conversation between two men begins. It doesn’t take long to understand why this throwaway track is remembered as Britain’s “first explicitly gay rock song.”

Listen below (starting around 2:20).

The dialogue sounds lifted from a discussion between two bitchy queens in the bathroom at any British gay spot from the era. There’s an air of horniness throughout the exchange, which takes place whilst cruising.

Though LGBTQ+ folks likely picked up on the context, the words were vague enough to confuse any heterosexual listener who made it that far. “Do you come here often,” one man starts. “Only when the pirate ships go off air,” the other replies.

Soon, they’re sh*t talking each other’s looks (“Well, I see pajama styled shirts are in, then.”) and making eyes with potential hookups. “Wow, these two coming now. What do you think,” one says. “Mmm … mine’s alright, but I don’t like the look of yours,” the other retorts.

Their farewell ends, of course, with a reference to Piccadilly Circus, known as the “centre of gay London” (and overall debauchery) in the ’50s and ’60s. “I’ll see you down the ‘Dilly,” the first man says. “Not if I see you first, you won’t,” his friend replies in a winking tone.

The voices in the track are presumably Tornados members Rob Huxley and Dave Watts, according to a YouTube comment from Watts. “We didn’t have a clue that it was something to do with gays,” he wrote, explaining that Meek directed the dialogue and “was giggling so much when [they] did the over dub.”

So, what was Joe Meek thinking when he slyly added this campy conversation to a major label release?

Perhaps it was an act of rebellion at a time when homosexuality was illegal in the UK. Parliament wouldn’t decriminalise “private homosexual acts between men aged over 21” until the next year.

Despite his success producing sleek and futuristic sounding records, Meek struggled with suppressing his sexuality. He feared his mother would learn he was gay, especially after his 1963 arrest for cruising (or “cottaging”).

Unfortunately, we will never know for sure. Meek, who struggled with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and addiction to amphetamines and barbiturates, reportedly shot his landlady and took his own life months after the single’s release. His fascination with the occult and paranoia around being outed likely contributed to his disturbed mental state.

Still, “Do You Come Here Often?” remains a landmark piece of LGBTQ+ music history.

Most notably, The Tornados track provides a time capsule of what it was like being queer in the ’60s. When a gay man’s only calling card was stolen glances in the men’s room, it reminds us that we’ve always had campy conversations to bring us levity.

Katie’s Pride: Diversity and Inclusion in the Workplace

Katie, co-founder of North Herts Pride, has designed a booklet aimed at raising awareness and helping people to understand issues that LGBTQ+ people in the workplace face.

Research Project

Nina Rabbitt, a Trainee Clinical Psychologist from The University of Manchester is conducting a research project looking at the experiences of lesbian and gay older adults who have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

This research will take place over the next 2 years.

There is currently no research looking at LGBT+ older adults’ experiences of having a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and how their experiences might have changed over time.

The aim is to start this conversation. They are conducting interviews with individuals aged 50 years old and above with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and who identify as cisgender and lesbian or gay.

Email bipolarstudy-lgoa@manchester.ac.uk or call 07971 331 537 to find out about participating in the study or for more information.