Ordsall Hall

Twenty six of us visited Ordsall Hall having had a great lunch at The Matchstick Man – a pub in Salford Quays referencing L S Lowry and his distinctive style of painting.

It was only a few minutes walk to Ordsall Hall, a large former manor house in the historic parish of Ordsall, now part of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester. It dates back more than 750 years, although the oldest surviving parts of the present hall were built in the 15th century.

The most important period of Ordsall Hall’s life was as the family seat of the Radclyffe family, who lived in the house for more than 300 years.

Since its sale by the Radclyffes in 1662 the hall has been put to many uses: a working men’s club, a school for clergy, and a radio station among them. The house was bought by the old Salford Council in 1959 and opened to the public in 1972, as a period house and local history museum. The hall is a Grade I listed building and entrance is free.

More photos can be seen here.

LGBT+ History Month

LGBT+ History Month is an annual celebration of the lives of LGBT+ people of the past. It is marked every February in the UK, with each year’s celebration having its own unique theme. To celebrate we are featuring an article from Arthur Martland.

Towards a Queer History of Wigan

Wigan has a long queer history, as do most other places in the UK. But where is it? And why is it not more widely known? At present all that has been identified would seem to be a few stray events, which are all in need of much further research. Not only is the paucity of historical records a problem, but also the fact that what has often been recorded has been penned by those who despise their queer brethren. Moreover, that which has been recorded is predominantly concerning queer men, where is the history of queer women, or of those who identify otherwise?

Crimes not fit to be named amongst Christians

The historian, H G Cocks, noted: ‘It is certainly the case that more men were executed and imprisoned for sodomy and other homosexual offences in the early nineteenth century than in any previous era of English history’ (i) and this fact is resonated in Wigan’s own queer history.

In 1806, following the raid on the house of Isaac Hitchin at Great Sankey, near Warrington, a socially-mixed group of 24 men (ranging from 17 to 84 years of age) were arrested, but only 9 men were prosecuted. Five of the men arrested and tried at the Lancaster Assize were hanged later that same year.

As the investigating magistrates, Richard Gwillyn and John Borron (ii), zealously continued their enquiries as to who else had frequented Hitchin’s house by interrogating those whom they had arrested and many more men were implicated. One of the accused, Thomas Rix, provided testimony regarding places in Liverpool and in Manchester where men could meet other men for sexual contact. He also gave information regarding those from higher social classes, whom he alleged were practising sodomites.

As information about the case spread like wildfire, so did rumour and speculation as to who else was involved. The local gentry and clergy were suspected. In a private letter written by Borron to Earl Spencer, who was, then, Secretary of State at the Home Office, on 20 September 1806, various names were cited. Those named, who were never publicly accused, included Meyrick Bankes of Winstanley, (who had been Sherrif of Cheshire in 1805), and various local South Lancashire MPs and clergymen, including the Revd Ireland Blackburne and the Revd Geoffrey Hornby, the Rector of Winwick.

Subsequently, many men were arrested on suspicion of being sodomites in Manchester and Liverpool, and investigations led to the arrest of a man from Wigan named Thomas Bolton. Little is known at present about the circumstances of Bolton’s arrest. However, such was the widespread interest in the crimes uncovered in Lancashire, that his conviction for ‘unnatural practices’ and for an ‘attempt to commit an unnatural crime at Wigan’ were recorded in both the Hereford Journal (8 April 1807) and the Lancaster Gazette (8 August 1807). In April 1807, Bolton was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment and ordered to stand on the pillory; the Gazette records that Bolton was placed in the pillory in the market place in Lancaster on Saturday 1 August 1807.

The active search for local sodomites seems to have palled after Bolton’s trial, but nationally further cases of alleged sodomitic activities continued apace. In 1810 in London, following a raid by the authorities on the White Swan molly house in Vere Street, several men were convicted of a variety of same-sex activities; two men were hanged and six placed on the pillory. Speculation intensified after the men were tried, as to who else had frequented the White Swan for sex with other men.

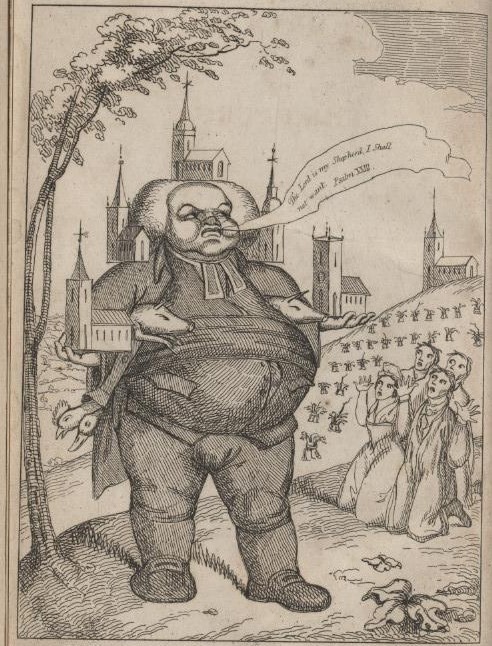

Eventually, in 1813, accusations were made against a dissenting minister, John Church. Lurid pamphlets, counter-pamphlets and newspaper reports were circulated accusing Church of ministering to the sodomites who visited the tavern. One writer, Robert Bell (iii), fulminated against, ‘the disgrace and pollution which Christianity might suffer from the immoral character of any of its teachers’ (p7), and ‘moral contagion that has been the ruin of Empires’ (p13). He alleged that the sodomites had ‘nominated’ John Church ‘to be their Chaplain; and that he officiated in that capacity. By virtue of his functions, in this situation he was often employed in joining these monsters in the “indissoluble tie of matrimony!!!‘ (p17). Bell urged others to join him in uncovering those who were causing the Christian religion to suffer ‘under disgrace and pollution’. (p14).

As with the Hitchin case, where local clerics had been suspected of being sodomites, the case of John Church highlighted the fact that Christian ministers were not immune from rumour and accusations. And we see again that seemingly distant cases and furores were mirrored in local events in Wigan for, in 1813, the same year that John Church had been denounced, the Rev George Hendrick, minister at All Saints Church in Hindley, was arrested and indicted as a sodomite.

Rev Hendrick was ‘charged with an assault, with an intent to commit an unnatural crime on Frederick Moult, a hair-dresser, at Knutsford. (Chester Courant 28 Sept 1813). Hendrick is reported as being in his 40s at the time of the offence, and Moult was 26 years of age. The alleged offence was said to have taken place at Moult’s barbershop in King Street. Hendrick was sent for trial at the Quarter Sessions in Chester.

His trial was reported, as follows, in the edition of the Chester Chronicle for Friday 17 September 1813 : –

Rev George Hendrick, aged 44, from Hindley, Lancashire, was next put to the bar, charged with an attempt at an offence, as the indictment emphatically mentioned, not fit to be named amongst Christians. – The trial occupied from ten o’clock in the morning till four o’clock in the and as we are prohibited by the Court from entering into the disgusting and unnatural details, we shall abstain from laying the evidence before the public. – We have therefore merely to say, that the evidence was not thought sufficient to conviction, and the prisoner was – Acquitted – The Court was unusually crowded. And here we should deem ourselves guilty of an act of injustice, were we not to say, that the eloquent and affecting address to the Jury, by Mr Cross, on behalf of the prisoner, was one of the finest specimens of elocution we ever heard in that court, or anywhere else.

(NB Minor spelling / typesetting errors in the original text above have been corrected, but no other changes made.)

Whilst the Rev Hendrick had been acquitted, his reputation never recovered. What few records that remain show his fall from grace, for whilst he officially held the living at All Saints until 1830 in reality the management of the church was placed in the hands of others. Looking at the Baptismal Register for All Saints from 1813 to 1840, baptisms by Hendrick ceased in July of 1813 with the majority of later ones being performed by the curate Hugh Evans. Evans went on to baptise at least five of his own children, no doubt, thereby, providing spurious evidence to his parishioners that he was unlike the Rev Hendrick in one major respect at least.

Despite conclusively having proved his innocence in one of the higher courts of the land, Hendrick was not allowed by the church authorities to escape without censure. He remained, in name at least, the incumbent of the parish, (ie the minister of the church), but as John Leyland in his book ‘Memorials of Hindley’ (iv), noted: –

‘In 1813 the living [ie the monies, benefices etc that were due to All Saints parish, which Hendrick as the incumbent could use as he thought fit] was sequestrated, [a legal process that removed control of Parish money from Hendrick and gave it to another appointed by the local bishop], in consequence of some impropriety, or alleged impropriety, on the part of the then incumbent, the Rev George Hendrick, and the Rev Hugh Evans was appointed curate in charge, the duties of which office he continued to discharge until Mr Hendrick’s death, in 1830.’ (p29)

Notwithstanding his efforts to cover parish duties, Evans did not succeed Hendrick as the incumbent of All Saints, as the next man to hold that office in the parish was Edward Hill.

© Arthur Martland

References:

(i) Cocks, H G ‘Safeguarding Civility: Sodomy, Class and Moral Reform in early nineteenth-century England’ in Past and Present no 190 (Feb 2006)

(ii) Borron achieved further notoriety in 1819 when he was one of the magistrates who ordered the militia into St Peter’s Field in Manchester.

(iii) Bell,’ Robert Religion and Morality Vindicated Against Hypocrisy and Pollution’ London: R Bell, 1813

(iv) Leyland, John ‘Memorials of Hindley’ Manchester: John Heywood, 1873.

Thanks to Arthur Martland for researching and writing this article.

‘This was my own tribe!’: Pride – in pictures

To celebrate LGBT+ History Month here are Sunil Gupta’s images of 80s Pride marches featuring cowboys … and only a few famous names. They recall a joyous time before corporate interests moved in.

When Sunil Gupta moved to London from New York in the late 70s, he was surprised to find no equivalent of New York’s Christopher Street. All the gays and lesbians appeared to be in hiding, found only in a handful of pubs and after-hours clubs. This changed with the 1970s fledgling gay marches. The photographs encompass Pride marches during the period from the mid to late 1980s.

Sunil Gupta: “This photograph is an example of how I was trying to wrestle with the idea of making reportage pictures of my own tribe, as it were, as opposed to a kind of media documentation of it from the outside. Sometimes, like here, I would approach somebody and look for eye contact and a raised glass.”

Sunil Gupta: “There was no commercial advertising allowed, only banners proclaiming people’s affiliation to organisations and the community. This banner refers to The Landmark Aids Centre, a day centre in Tulse Hill which offered treatment and support for HIV patients. It was officially opened on 25 July 1989 by Diana, Princess of Wales. It’s one of the occasions where Diana shook the hands of somebody with HIV. In this case, the director, Jonathan Grimshaw.”

Sunil Gupta: “These are the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a worldwide order that was founded in San Francisco in 1979. The London base was at the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in Farringdon while it was open. They are well known for their street protests dressed as nuns and campaigning for sexual health in the fight against Aids. The London branch reformed in 2007 and became known as The London House of Common Sluts.”

Sunil Gupta: “A wider view, it gives a sense of space and place. In fact, it’s the southern end of Kennington Road, and it captures the way the community was both marching on the road and spilling out on to the pavements without too much policing and no cordoning off at all.”

Sunil Gupta: “Kennington Park felt very informal and free like a giant community picnic, which is how I mostly recall my experience of the 80s Pride marches before commercial pressures kicked in.”