Victoria Hall

This week we visited Victoria Hall in Bolton, a Methodist church, but also a hub for the local community, which has performances of concerts and pantomimes.

Influenced by a visit to the Manchester Mission, Thomas Walker proposed a similar Mission Hall be built in Bolton. The new Mission Hall was built on land belonging to Ridgway Gates Chapel. A terrace of eight shops was bought with the middle four being demolished so that an entrance to the main hall could be created from the main street. The other shops were let to provide an income for the Mission.

In 1897 the architects Bradshaw Gass were commissioned to build the finest hall in England, based on the design of the popular music halls. It was felt that non-church people would feel more comfortable in such surroundings.

The Victoria Hall was opened in 1900 in the style of a music hall with over 1,250 seats at a cost of £30,000. The acoustics were amazing in the large hall.

With Barry, our knowledgeable and enthusiastic guide, we explored the never-ending halls, sweeping staircases and simply superb architecture that makes up Victoria Hall.

More photos can be seen here.

Holocaust Memorial Day

Holocaust Memorial Day is an annual observance to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust, the genocide of six million Jews and of millions of other Holocaust victims by Nazi Germany and its collaborators.

The day is observed on 27 January, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp in 1945.

Here are the stories of Dorothea Neff and Fritz Bauer:

Dorothea Neff & Lilli Wolff

Dorothea Neff was an actress. She was born in Munich, Germany, in 1903. In the 1930s, she acted in a theatre in Cologne, where she met the young Jewish costume designer, Lilli Wolff. The two women started a romantic relationship. When Neff was offered a position with the famous Volkstheater in Vienna and moved there, the two women’s paths diverged.

In 1940, however, as the situation of the Jews in her hometown deteriorated, Lilli decided to go to Vienna, erroneously believing that Jews were better treated there. Desperate and lonely in a city where she knew no one, Lilli went to her former lover’s apartment and asked her for help. Neff found her a room with another Jewish family, assisted her financially and supplied her with necessary medication and other needs.

Moreover, at a time when almost all Germans and Austrians had totally cut off contact with Jews, Dorothea often came to visit her friend. Although the Jews’ freedom of movement was severely restricted by that time, Dorothea invited Lilli over to her apartment.

When the deportations of the Jews to the East began, Dorothea tried in vain to find a hiding-place for her friend, and even went to Berlin for that purpose. It seems that she reached the conclusion that she had exhausted all possibilities of helping her friend. Thus, in October of 1941, when Lilli received notification that she was to be deported, Dorothea came to help her pack her belongings and to see her off.

After the war, the two women related that they had been sitting in the kitchen, trying to decide what Lilli should pack to take to her unknown destination. It was a sudden spontaneous impulse that made Dorothea close the suitcase and exclaim: “You’re not going anywhere! I’ll hide you!” This was clearly not something she had planned in advance. Until that moment she had thought there was nothing more to be done, and only while they were packing did she realise that she had to take one more step.

Years later, she explained: “As I looked into Lilli’s pale face, I was so overcome by compassion for this poor abandoned human being that I knew I couldn’t let her go off to face the unknown.”

For over three years, until the end of the war, Lilli lived in a back room in Dorothea’s apartment. The two women were in constant fear of discovery. For Lilli it was the terror of being caught and deported. But the rescuer’s life changed radically as well. She would rush home every day after her performance, worrying that something might have happened during her absence. At a time of war, when food was rationed, she had to obtain extra food for her friend. During air raids, she had to find excuses to explain the stranger who would join her down at the shelter. She had to be careful about whom she invited to her home.

Another crisis came when Lilli became sick. Like many other rescuers who were hiding Jews, Dorothea now had to find a way to take Lilli to get treatment without arousing suspicion. Finally, their romantic relationship ended, yet Dorothea continued to hide Lilli in her home.

After the war, Lilli Wolff immigrated to the United States and settled in Dallas, Texas.

In 1979, Dorothea Neff was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

In her speech she said:

“The greater the darkness of a period, the brighter is the light of a single candle.”

Fritz Bauer, gay Holocaust survivor-turned-Nazi hunter, took down one of the Reich’s most prominent leaders

He was a methodical and efficiently non-violent Nazi hunter. A dark-eyed chain smoker with the cultivated calm of a judge, Fritz Bauer single-handedly brought dozens of war criminals to justice for an untold number of human rights offences. But because he was homosexual and embarrassed too many mediocre yet powerful men, he was vilified in his own lifetime as a “degenerate” and “criminal,” He was then lost to history for decades, rather than honoured publicly for his courageous advocacy in the shadow of fascism.

Born in 1903 in Stuttgart, Germany, Bauer was raised in an affluent and liberal Jewish family. Though denied entrance to the most elite fraternities because of his heritage, Fritz ultimately thrived in law school and quickly ascended to the position of “assessor judge,” or junior prosecutor – Germany’s youngest on record – at 27.

Unfortunately, this milestone appointment landed in 1930, just in time for the zealots of the Third Reich to begin dismantling the legal system and the country. A member of the Social Democratic Party, Bauer found himself surrounded by “conservative and authoritarian in spirit” colleagues. He was demoted in 1931 after being smeared by Nazi columnist Adolf Gerlach in a local paper as a “biased” Jew and communist sympathiser incapable of competently doing his job.

By 1933, Nazi rule had insured Bauer was arrested while working at his office – without charges – and condemned to the Heuberg concentration camp, where he was targeted aggressively by brownshirt guards for being both Jewish and a political threat to the Nazi regime. Though not labelled with the dreaded “pink triangle,” some accounts of his life suggest Bauer’s unmarried status and progressive leanings had by this point already outed him in the eyes of the fatally homophobic Nazis.

In November 1933, Bauer was offered exile if he participated in a propagandist PR stunt. In exchange for his signature on a public statement switching allegiance from the Social Democrat to the Nazi party, Fritz was formally discharged as a judge but released from the camps and allowed to escape to Denmark … which wasn’t exactly the reprieve it sounds like.

Bauer was arrested in 1936 for suspicion of homosexual sex with “a male prostitute”. Fritz vehemently denied money being involved and the other man being a sex worker, but he did not refute their involvement and was later forced into another internment camp, this time by Nazi-sympathetic Danish authorities.

Not long thereafter, Bauer legally married a Danish kindergarten teacher named Anna Maria Petersen and fled secretly via fishing boat to Sweden to wait out the rest of the war.

The end of WWII by no means meant the end of Nazi influence, however. Fascist ideology still permeated both international politics and local, civilian post-war life. German nationalists continued to support Nazi players even in light of their defeat. Bauer returned home to West Germany in 1949 to finally resume his service as a judge but found a traumatic landscape where men who’d committed genocide against his community were rewarded with positions of ongoing power and influence. Through diligent work, Bauer nonetheless climbed the ranks of the district courts and was appointed state prosecutor in Frankfurt in 1956.

Bauer’s very rare combination of tangible judicial power and personal camaraderie with other concentration camp survivors put him in the position to actually do something about Nazis living karma-free internationally, though he was forced to hide his Jewish identity, homosexuality, and Holocaust-survivor status in order to get anything done. To this day, biographies of his life tend to downplay or completely erase his homosexuality.

Bauer’s long-game tactics took down one of the major coordinators of the genocide, Otto Adolf Eichman. Eichman literally helped arrange and manage the deportation of Jews into extermination camps. Eichmann was captured in 1945 by the US military but soon escaped to a sedate life in Argentina with the help of a Catholic bishop. Eichmann, like many other Nazi fugitives at the time, made little effort to hide himself or his history – part of the reason he was recaptured was his own son, Klaus, bragging to women about daddy being a Nazi and murderer.

The rest of the reason was the patience of Bauer, who knew Nazi sympathizers in the West German judicial system would only protect Eichmann by tipping him off, or worse, helping move him with German money.

So Bauer committed light treason.

In violation of German law, Bauer bypassed his country’s intelligence entirely, reaching out directly to Israeli Mossad director Isser Harel with Eichmann’s exact location, a recent photo, and details on the family’s braggadocio. Israeli officials worked with Bauer’s tipsters to get Eichmann forcefully extradited for trial from Argentina to Israel – a place where compromised German officials, who initially tried to get Bauer in trouble instead of assisting with the prosecution of a Nazi, couldn’t interfere with justice.

Eichmann was ultimately found guilty and executed for his participation in the mass extermination of millions of civilians. Back home, Bauer was accused of “fouling his own nest” and received death threats.

Undeterred, Bauer pushed this victory further by certifying a class-action lawsuit now recognised as the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials. Over the course of several years, the case brought formal charges against 22 members of the SS – the tiniest fraction of the estimated 7000+ Nazi-affiliated individuals believed to assist in running the death camps.

Though deemed a “failure” by Bauer himself, the trials were pivotal in alerting the world to the secretive, but at that point still broadly covered-up, machinations of the SS. The testimony of the 22 defendants and 800+ sources interviewed across a half-decade of pre-trial research became the backbone of our global understanding of what unchecked fascist rule truly looks like. They are preserved in UNESCO’s Memory of the World archives.

When not trailing and convicting Nazis, Bauer quietly attempted to move the dial of progress by advocating for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the German penal code. In the 1950s and 60s, it was an outright crime to simply identify as gay or queer, with additional charges for participating in same-sex activities.

Bauer was found dead in his own bathtub in 1968 at the age of 64 in what was deemed “suspicious circumstances.” A coroner’s report asserted that Bauer had accidentally died of a combination of sleeping pills and alcohol – not impossible for a man in the highest stress position imaginable. But colleagues at his Humanist Union and in the larger social justice community wondered if, given the years of death threats, Bauer had not perhaps been killed by people who had already proven themselves to be murderers.

An acclaimed feature film about his life, The State Versus Fritz Bauer won an award at the Berlin Film Festival in 2016.

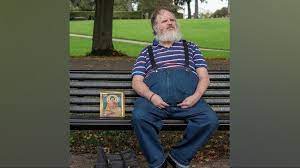

LGBT+ exhibition shows lives of older generation

An exhibition showing the lives of Shropshire’s older LGBT+ generations hopes to challenge stereotypes.

Photographer Ming de Nasty worked with residents in 2023, touching on how LGBT+ culture had changed, as well as sharing memories and old images.

The display, at Theatre Severn, Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery and Shrewsbury Library runs until 14 April.

The photographer said her subjects had “rich and diverse histories and very active lives. We don’t disappear after the age of 50,” she added.

The exhibition is a partnership between SAND, a community organisation that aims to improve the experiences of LGBT+ people as they age in Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin; Midlands-based photography organisation GRAIN; and Arts Council England.

The photographs show residents expressing a confidence and sense of identity in their gaze and position, according to the photographer.

The exhibition also features information about their younger lives, family backgrounds and the changes in LGBT+ culture and law.

Sal Hampson, director of SAND, said: “The process of taking part and the exhibition and publication outcomes will contribute to a future where lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people in Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin are fully integrated into the community.”

Ming de Nasty, 70, has been a professional photographer for 35 years and recent projects include Queer Country, a photographic project with a focus on individuals’ experiences in Wales, and what it means to be living in a rural environment.

“I left Shropshire (for Birmingham in the 1980s) because I’m gay and there wasn’t much here for me,” the artist said. “It isn’t out and loud as it is in the city but there is a community here now. I am in the older age bracket now and we need to share wisdom to the younger generation.”

The exhibition will also be shown at The Hive in Shrewsbury as part of the LGBT+ History Festival in March.