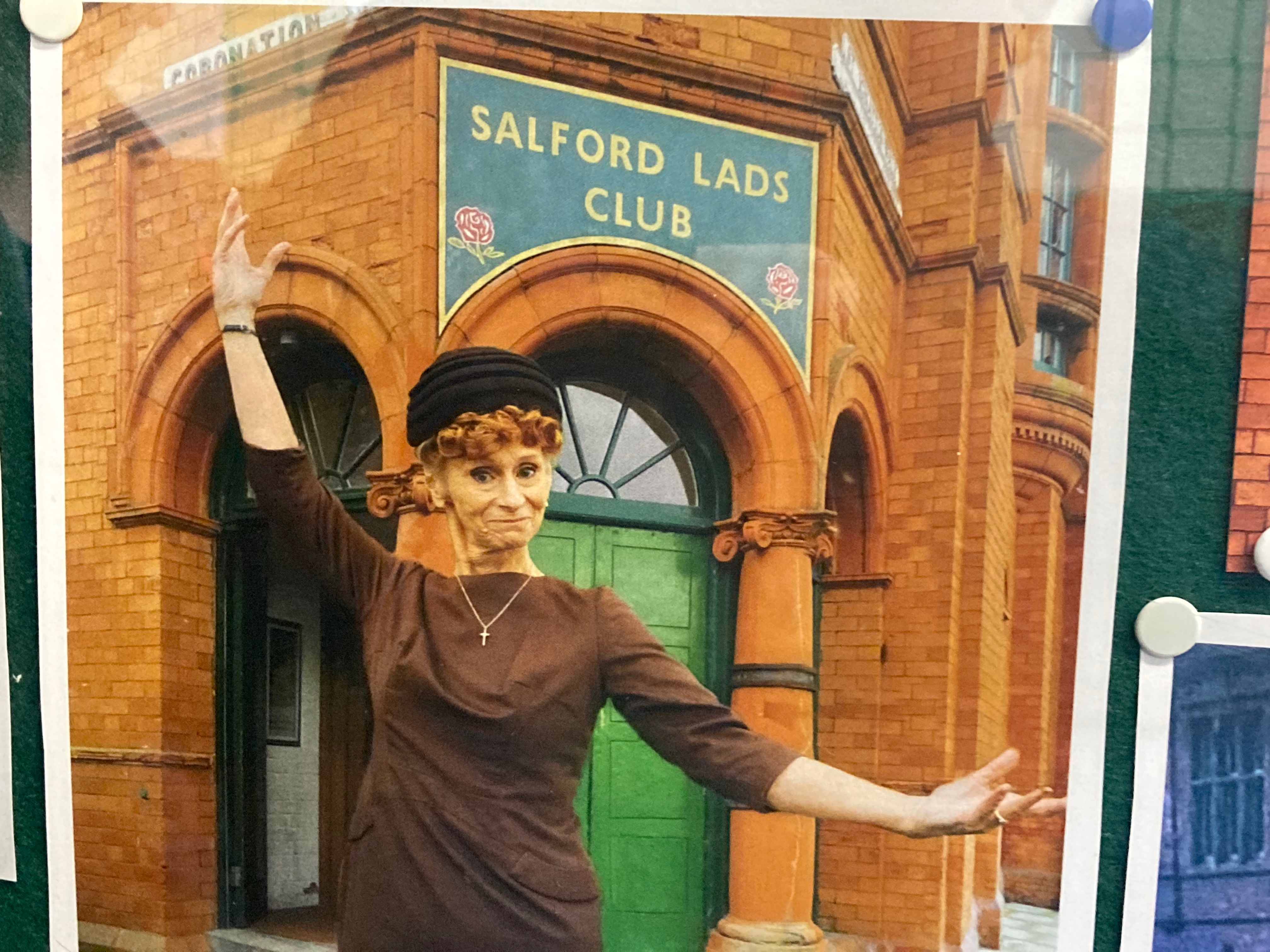

Salford Lads and Girls Club

First of all, let’s get this straight: The building is called “Salford Lads Club”, but the charity is called “Salford Lads and Girls Club”. They provide a wide range of activities for local young people.

Salford Lads Club was established as a purpose built club for boys. The site was officially opened on 24 August 1903 as a club for working lads, providing a positive alternative to the teenage street gangs (known as “scuttlers”) in the poorest areas of the city.

The club has continued to provide this facility for more than 100 years and is now considered to be the finest example of a pre First World War club surviving and operating today.

Founded by the Groves brothers of the Groves & Whitnall brewing empire, the current club president and Chair of Trustees, Anthony Groves, is the great grandson of James Grimble Groves!

The club is now open to girls and boys.

While nearly all other original working class lads club buildings are long gone, along with their records, the continuity of Salford Lads Club in 2023 makes it very special for generations of families. They still have all their membership cards since their foundation, and in 2015 they created a remarkable “Wall of Names” to share over 22,500 members’ names dating back to 1903.

There are a few famous names among the archive boxes: Eddie Colman, the young Manchester United star player who died in the 1958 Munich Air Disaster; Allan Clarke and Graham Nash who went on to form 1960’s pop group The Hollies; and “Mr Muscle” – Tony Holland of ‘Opportunity Knocks’ fame in the 1960s.

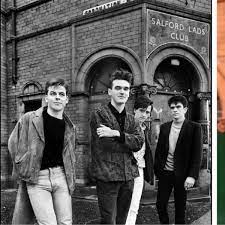

The club has also been the site of pilgrimage for fans of The Smiths after Stephen Wright’s iconic photo of the band was used on the inner sleeve of ‘The Queen is Dead’ album in 1986. In 2004, the club opened a dedicated Smiths room where fan photos are displayed alongside post-it messages. The club continues to welcome visitors weekly – from Indonesia to Mexico, Israel to Australia, much of Europe, Canada, America and South America.

The club’s original motto is: “to brighten young lives and make good citizens.”

More photos can be seen here.

Hate crimes against LGBT+ people

The Westminster Hall Debate “Hate Crimes against the LGBT+ community” was held on Wednesday, 18 October at 4.30pm.

There was a call for a national action plan to deal with rising homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic hate crimes, and for all members of Government and Parliament to stop legitimising hatred against trans people with fear-mongering rhetoric.

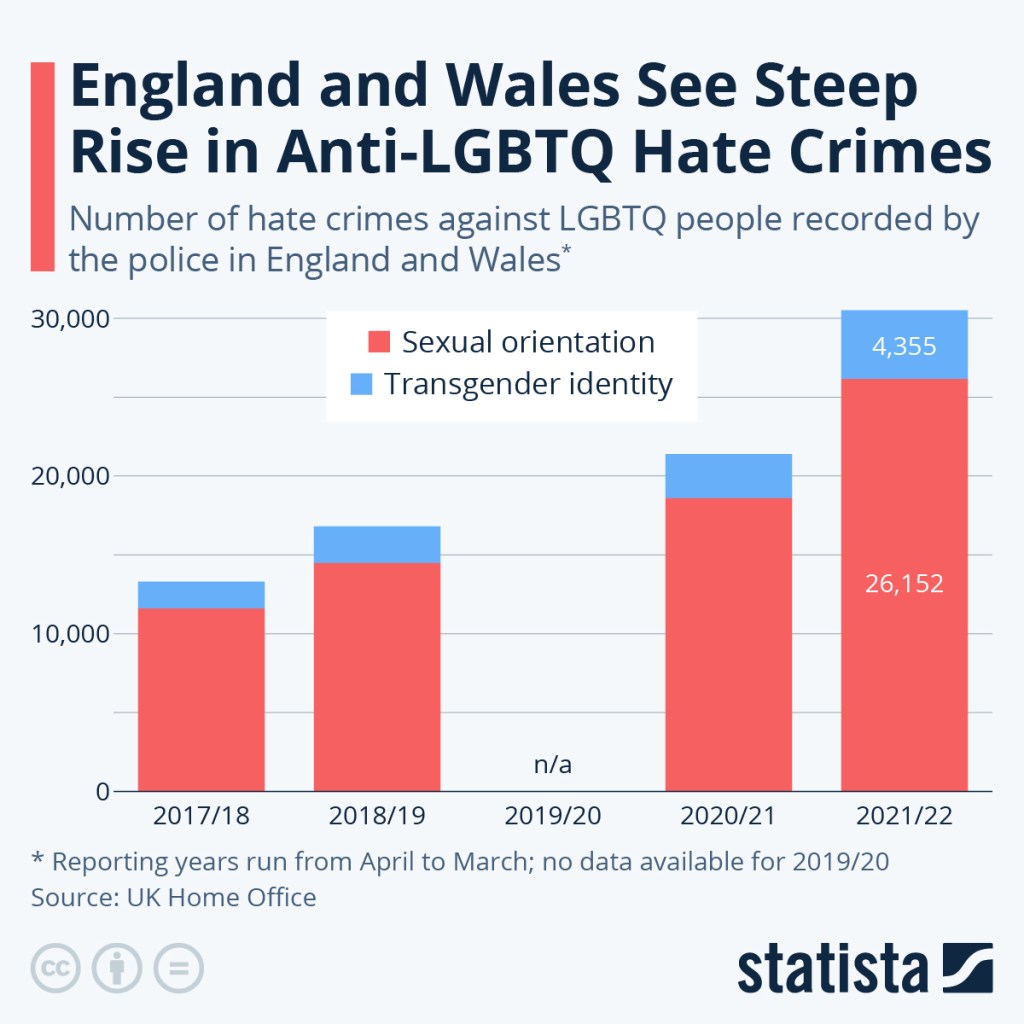

New statistics released by the Home Office this month show a continued rise in hate crimes against lesbian, gay, bi and trans people in England and Wales.

- Hate crimes against trans people in England and Wales have risen by 11% in a year, and by 186% in the last five years

- Hate crimes on the basis of sexual orientation in England and Wales are up by 112% in the last five years, despite this year’s slight decrease of 6%

- The Government’s own National LGBT Survey showed fewer than one in ten LGBT+ people report hate crimes or incidents. Only 37% of those who experienced an anti-LGBT+ hate crime involving physical harassment or violence reported it.

These findings come as a manufactured culture war spreads divisive rhetoric and misinformation in our politics and media, that is legitimising hatred against the LGBT+ community, and trans people in particular.

Earlier this month we saw Government Ministers using their platform not to encourage respect, but rather to posture policies designed to drum up “culture war” and “anti-woke” political noise by attacking trans people. In fact, the Home Office’s own release pointed to the increase in discussion of trans issues by politicians, in the media, and online, as a potential contributing factor to the increase in reported hate crimes.

The statistics show the impact of this rising hateful narrative – real violence, harassment, and abuse of LGBT+ people up and down this country.

National Hate Crime Awareness Week is 14 – 21 October 2023. We expect our Members of Parliament to call out the rising hate faced by an already vulnerable community, and to show that they stand against ongoing attempts to turn political debates into an offensive and dangerous attack on our rights and existence.

Get Online Week 2023

This week we will be celebrating Get Online Week (16 – 23 October 2023) – a week dedicated to helping people get online safely, confidently and affordably.

Manchester Adult Education Services offers free digital skills courses such as Digital Skills for Beginners, Essential Digital Skills, Microsoft for Work and Being Cyber Safe – all developed to build your confidence in both home and workplace settings and keep you safe online.

If you don’t want to apply for a course but would like some advice on accessing services online, how to use a particular device or search for information quickly, why not attend one of the Skill Up Workshops? These casual, no commitment drop-in sessions are perfect for support and a place where no question is too small.

Skill Up Workshop timetable:

- Abraham Moss Adult Learning Centre: Thursdays from 9:30am – 11:45am

- Fallowfield Library: Thursdays from 1:00pm – 3:00pm

- Wythenshawe Forum: Wednesdays from 9:30am – 11:45am

- Greenheys Adult Learning Centre: Tuesdays from 9:30am – 11:45am

- Gorton Hub: Tuesdays from 12:30pm – 2:45pm

- Longsight Library and Adult Learning Centre: Mondays from 9:30am – 11:45am

- The Avenue: Fridays from 9:30am – 11:45am

- Withington Adult Learning Centre: Wednesdays from 12:30pm – 2:45pm.

“Molly” men flocked to these secret 18th-century gay clubs to mingle, have sex and mock straight people

Until the repeal of the Buggery Act in 1861, gay sex was a capital offence. However, even during the extremely hostile environment before the repeal, “Molly Houses”, often coffee houses, pubs or taverns, were created where people could meet and socialise.

Named after the slang term “molly”, which was usually used to refer to effeminate, homosexual men, Molly Houses quickly became the go-to meeting place for gay men in 18th century.

In court records from a buggery trial in 1724, a policeman named Joseph Sellers who visited a Molly House reported seeing “a company of men fiddling and dancing and singing bawdy songs, kissing and using their hands in a very unseemly manner.”

What is clear from reports at the time, typically from testimonies given in court cases, are the mock rituals the Mollies would perform: from adopting a female persona, alongside a feminine name and mannerisms, to cross-dressing on Festival Nights and conducting mock births and marriages.

Many of the sexual encounters and rituals were comedic in nature and were aimed at making a masquerade of straight conventions and parodying aristocratic manners.

“They were a forum for comedy and performance, where the whole idea of what’s true and natural gets called into question,” explains Matt Cook, the UK’s first Professor of LGBTQ+ History at the University of Oxford. “They served an important function for people to play with convention, ritual and to explore, have sex and socialise.”

The rise and fall of Mother Clap’s Molly House

Found on Field Lane in Holborn, central London, Mother Clap’s Molly House was arguably the most well-known and infamous molly house in 18th century London. Run by Margaret “Mother” Clap, this venue regularly accommodated dozens of men with beds being placed in all the rooms, thanks to Mother Clap.

The popularity of Mother Clap’s would ultimately prove to be its downfall, with a member of the puritan Society for the Reformation of Manners, Samuel Stevens, going undercover at the club to expose the patrons.

After visiting Mother Clap’s on 14 November 1725, Stevens said he saw men making love to one another and kissing in a lewd manner. “Then they would get up, dance and make curtsies, and mimick the voices of women. Then they’d hug, and play, and toy, and go out by couples into another room on the same floor, to be marry’d, as they call’d it.”

Police constables descended upon Mother Clap’s in February 1726, blocking all exits and arresting forty men. While most were released due to a lack of evidence, Mother Clap herself and a handful of customers received fines and prison sentences and were put in the pillory.

Three guests, Gabriel Lawrence, William Griffin, and Thomas Wright, were found guilty of buggery and hanged on 9 May 1726.

The limits of inclusion

A handful of other Molly Houses have been identified in London and other cities, including Plump Nelly’s Molly House in London’s Smithfield and a public house on the edge of Warrington, near Manchester.

There is no question that the legal climate at the time when Molly Houses existed was deeply repressive towards men who had sex with men. Yet, for Cook, the lack of a distinct homosexual identity during the 18th and 19th centuries makes it a challenge for historians today to say exactly what motivated Molly House patrons.

“There was still a sense of it being an act rather than an identity. We don’t know really what the people who went to the Molly Houses were thinking of themselves,” he explains.

While there are mentions of upper-class men visiting, or slumming it, in Molly Houses, Cook warns against viewing Molly Houses as utopian environments, where class differences in 18th century England simply disappeared.

“If you just look at who was arrested and prosecuted, there are no upper-class men there. I think it’s a mistake to think of them as kind of all-inclusive spaces – I don’t think they functioned like that at all.”

Relying on unreliable storytellers

Despite only being open from 1724 to 1726, Mother Clap’s Molly House and its eccentric owner managed to create a sanctuary in a deeply repressive society. Even its raid and subsequent arrests helped provide historians today with unrivalled insights about gay life in England centuries ago.

The vast majority of primary sources about the Molly Houses are related to court cases or pamphlets distributed at the time. Much of the historical record comes directly from people who infiltrated Molly Houses undercover and then testified in court against customers.

“Often the only times when marginalised lives get reported on is when the law gets involved,” says English playwright Mark Ravenhill, who wrote the 2001 play, Mother Clap’s Molly House, set in part in 1720s London. “The facts available to us have been slightly distorted because they’re all from the prosecution, who are trying to shut down the houses.”

The growth of Molly Houses from around 1690 to 1726, and the following crackdown, interested Ravenhill and led him to set his play in the 1720s.

“After reading the material, I just thought it’s such a fascinating history. But there also seemed to be a very inherent theatrical element to the stories – I could easily see them on a big stage with lots of costume, music and dancing.”

Despite the immense importance these places had in allowing gay people to be themselves and in the process create a distinct subculture, their existence is still not widely known. “People still on the whole haven’t heard about these places,” concludes Ravenhill. “As soon as you start to tell them about that culture, it just blows their mind and they want to know more about Molly Houses.”