Llangollen

On Thursday 15 June, Out In The City members visited Plas Newydd at Llangollen.

It was a really enjoyable trip to the fascinating home of Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby – the two Ladies of Llangollen.

They were two upper-class Irish women who lived together as a couple. Their relationship scandalised and fascinated their contemporaries. The pair moved to Llangollen, North Wales, in 1780 after leaving Ireland to escape the social pressures of conventional marriages. Plas Newydd was originally a five-roomed stone cottage, but over the years it was enlarged to include many Gothic features. The elaborately carved oak features were amazing.

Over the years, numerous distinguished visitors called upon them. Guests included Percy Bysshe Shelley, the Duke of Wellington and William Wordsworth, the latter of whom wrote a sonnet about them.

Anne Lister, dubbed “the first modern lesbian” also visited the couple, and was possibly inspired by their relationship to informally marry her own lover.

Butler and Ponsonby lived together for 50 years. There is nothing in their extensive correspondence or diaries that indicates a sexual relationship, but a succession of their pet dogs were named “Sappho”.

We also had time to visit the town and lots of photos can be seen here.

Pride in Wythenshawe

Pride in Wythenshawe is a celebration of LGBTQ+ people with fun activities for all.

It is held at Woodhouse Park Lifestyle Centre, 206 Portway, Wythenshawe, Manchester M22 1QW on Saturday, 24 June from 1.00pm to 5.00pm.

Get your FREE tickets now, using this link.

Publishing Queer Berlin

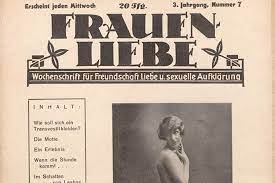

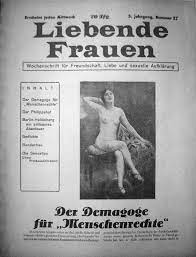

Berlin in the 1920s was ablaze with sexual and gender freedom. Magazines at news stands boasted covers featuring people who were transgender and clad scantily. Their headlines touted stories on “Homosexual Women and the Upcoming Legislative Elections,” and offered, on occasion, homoerotic fiction inside its pages.

Publications like Die Freundin (The Girlfriend); Frauenliebe (Women Love, which later became Garçonne); and Das 3. Geschlecht (The Third Sex, which included writers who might identify as transgender today), found dedicated audiences who read their takes on culture and nightlife as well as the social and political issues of the day. The relaxed censorship rules under the Weimar Republic enabled lesbian writers to establish themselves professionally while also giving them an opportunity to legitimise an identity that only a few years later would be under threat.

A growing group of academics are focusing on this oft-forgotten moment in German history. The primary source documents that miraculously survived the period of the Third Reich and subsequent and repressive Cold War years provide a rich and complicated picture.

There were some twenty-five to thirty queer publications in Berlin between 1919 and 1933, most of which published around eight pages of articles on a bi-weekly basis. Of these, at least six were specifically oriented toward lesbians. What made them unique is the space they made for lesbians, who had traditionally been marginalised on account of both gender and sexuality, to grapple with their role in a rapidly changing society.

In these interwar years in Germany, queer and transgender identity became more accepted, in large part thanks to the work of Magnus Hirschfeld, a Jewish doctor whose Institut für Sexualwissenschaft focused on issues of gender, sex, and sexuality. At the same time, women in Germany were making strides toward greater independence and equity; they gained the right to vote in 1918, and feminist organisations like Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine cultivated space for women in public spheres, encouraging their advancement in politics. The German Communist Party created the Red Women and Girls’ League in 1925 to attract more women and working-class people, particularly through organising factory workers.

More generally, German women were becoming increasingly empowered. Queer people—including women—rallied around the abolishment of contemporary sodomy laws. This struggle “created a wider climate of publication, activism, and social organisation that was much more embracing of different types of queer and trans lives,” according to Katie Sutton, an associate professor of German and gender studies at the Australian National University.

Sutton came upon the Weimar-era lesbian publications in Berlin and was surprised that there wasn’t more engagement with these magazines or with the queer history of the Weimar Republic more broadly on the part of academics in the English-speaking world.

Magazine fiction of the time challenged some of the restrictions of class and race in its love stories. These publications also created a space for readers to assert themselves in the real world through personal ads and event listings. There included cream puff eating contests, ladies and trans balls, and lake excursions on paddle steamers. In fact, aspects of lesbian culture also seeped into the mainstream, particularly when it came to fashion, with a rise in the popularity of short haircuts, straight skirts, and pantsuits. There was little difference between the imagery in mainstream fashion magazines and the masculinised aesthetic eroticised in the queer ones. The “hint of queerness” in the mainstream, Sutton said, was “sexy and fascinating, but also a bit scary and potentially off putting.” A popular element in lesbian publications, the monocle was similarly charged, and, Sutton says, “a queerly coded, quite masculine symbol of owning the gaze.”

Such sartorial choices were in keeping with debates in the lesbian magazines of the time around the “extent that masculinity might be seen as hierarchically superior to that of the feminine lesbian women,” according to Sutton. Moreover, these debates foreshadowed the butch/femme debates of the 1980s and 1990s.

Style was particularly significant for trans women and men who in the Weimar Republic defined themselves with a variety of terms: both as transvestites and masculine women who wore men’s clothes but identified as women. Trans people were given space in both their own magazines and even in some of the lesbian ones, highlighting a sense of cross-identity camaraderie. Die Freundin had a regular trans supplement highlighting these voices.

In a 1929 issue, a writer named Elly R criticised the treatment of trans people in mainstream media, referencing sensational coverage of men wearing their wives’ wedding dresses. “Everywhere in nature we find transitional forms, in the physical and chemical bodies, in the plants and the animals,” she wrote. “Everywhere one form passes into another, and everywhere there is a connection. Nowhere in nature is there a delimited, fixed type. Is it only in man that this transition should be missing? As there is no fixed form in nature, a strict separation between the sexes is also impossible.”

These magazines were resilient, a testament to the strength of the communities they served. Still, they faced challenges. The 1926 Harmful Publications Act was intended to impose moral censorship on the widespread pulp literature sold at kiosks and news stands, including the queer publications, which often featured nude photographs.

The Catholic and Protestant Churches as well as public morality organisations and conservative politicians led the fight against what they called “trash and filth literature.” As Klaus Petersen explains in a German Studies Review article, the list of materials, which included at least seventy works on sexology and “filth literature,” could still be sold, just not to those under age eighteen. While “the instrument was blunt and [its] impact minimal,” the restriction was boosted by members of religious and youth groups that checked up on news stands to see what material was visible or advertised to children. (This is not a far cry from the Nazi book burnings that would occur just a few years later.) But the law also spurred a counter-campaign by writers, publishers, intellectuals, and leftist political activists who objected to these limitations, as Petersen explains.

“This coalition of protest groups against infringements of the freedom of expression considered the Index a simplistic and entirely ineffective means to avoid an honest discussion of the fast change in social attitudes and moral values and campaigned against it as an unconstitutional instrument of suppression.”

Despite their relative progressivism, these publications also represented a rather narrow, bourgeois segment of the German population. Even if women had greater access to education and publishing opportunities, the women who enjoyed this greater access were largely urban elites. Little if no space was given to proletarian struggles.

It’s also important to note that whatever sexual liberation the LGBT+ community enjoyed was at the discretion of the state, whose goal was to control its members. This was seen in the Transvestitenscheine (“transvestite certificates”) handed out by the German police to protect against the arrest of those cross-dressing in public. Between 1908-1933, dozens of such passes were distributed. They also guarded against arrests for sodomy law violations and played a role in a 1927 battle over legalising prostitution, largely aimed at preventing the spread of venereal diseases.

More notably, these magazines gave precious little foresight into what was to come in Germany: the attempted extermination of all who did not fit the Aryan ideal. That, of course, included lesbians, some of whom perhaps took steps to save their own skin. Ruth Roellig, who wrote for Frauenliebe and published Berlins lesbische Frauen (Berlin’s Lesbian Women) in 1928, a first-of-its-kind travel guide to queer Berlin, published a second book in 1937. Soldaten, Tod, Tänzerin (Soldiers, Death, Dancer), an anti-Semitic screed, proved to be Roellig’s last book, though she lived until 1969. Selli Engler, a lesbian editor who founded the magazine Die BIF – Blätter Idealer Frauenfreundschaften (Papers on Ideal Women Friendships), wrote Heil Hitler, a play she sent directly to the führer.

As feminist and queer activism grew in Germany in the 1970s, so too did interest in the Weimar period. In 1973, Homosexual Action West Berlin began to collect flyers, posters, and press releases in an effort to create a comprehensive archive of lesbian history. The group eventually morphed into Spinnboden, Europe’s largest and oldest lesbian archive, with more than 50 thousand items in its holdings, magazines among them. Katja Koblitz, who runs the archive, says the existence of these lesbian periodicals is invaluable. “These magazines were in one part a sign of the blossoming and of the richness of the lesbian subculture in these days,” she said. “Reading these magazines was a form of reassurance: here we are, we exist.”